Why I Am Not a PhD

English departments teach theory, not literature.

I used to get into quarrels with my high school math teacher. Every morning, he would stroll into class with a stack of notebooks, a pack of chalk, and a jab at our school’s English department. As a future English major, I felt it was my duty to speak up.

The irony was that I had never particularly liked any of our English teachers. They did their part, but they always taught literature through overarching themes: “the failures of capitalism in The Great Gatsby” or “the proto-feminism of The Canterbury Tales.” I didn’t particularly care about such themes, and by the end of high school, I had grown increasingly skeptical of the way my teachers approached literature. Instead, I turned my sights on America’s liberal-arts university system, where I hoped to find a more open-minded environment. I dreamed of becoming an English professor.

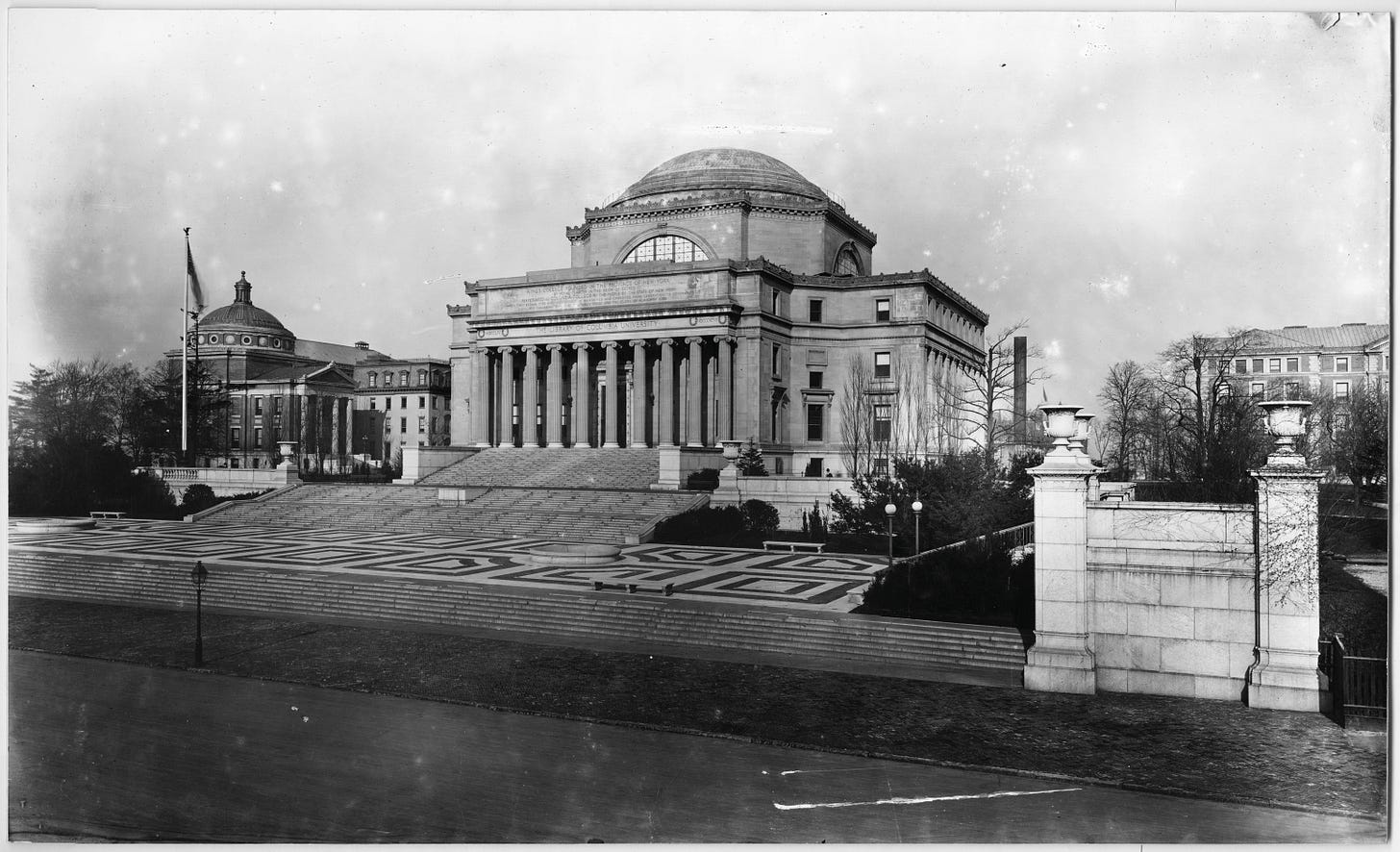

When I got to Columbia University—one of the world’s leading institutions for English literary scholarship—my fascination with the literary world initially grew. In my freshman year, I sat around my dorm reciting poems to my peers and conjugating Latin verbs in preparation to read Virgil and Ovid. For a fleeting moment, I was enamored—I didn’t have to take a single math class, and my peers had heard of Dante.

So the C that I received on my first English paper was a blow. I sat in my professor’s office dumbfounded by his evaluation of my argument that, during times of loss, women in the Iliad found the most solace in their male counterparts. I had spent several days on the paper and wanted him to explain what was wrong with my argument. He glared at me.

“It is incorrect to argue that a patriarchal structure can benefit society’s women.”

Perplexed, I poured my ire into my next paper, where I argued something about subverting gender roles in The Oresteia. In contrast to my first paper, I threw this one together in about two hours. It received an A.

I knew from that moment that something was wrong at Columbia, too. At the very least I found myself wondering if I was just an outlier in the literary world. Coming from an immigrant background—with parents from the USSR who had suffered under socialism—it bothered me that Karl Marx seemed to feature on my English syllabi more frequently than Shakespeare or Milton. I was deeply convinced that literature was not a vehicle for social activism; rather, it was a unique window into human nature, tackling questions far more fundamental than political divisions. Yet not a single student or professor in my department seemed to welcome my perspective.

Two years later, I fancied myself a Shakespeare scholar and enrolled in a Shakespeare survey course. The professor was a recent hire with little teaching experience, but when she stood before the lecture hall, there was not a single cell phone or slumping senior in sight. She radiated platitudes and themes, spouted all the buzzwords—heteronormativity and racial politics—and put a leftist spin on every play. It all fed my appetite for absurdity until one day I found a messy scrawl at the top of my midterm exam: Don’t forget to mention queer desire in A Midsummer Night’s Dream.

I wanted to know how we had ended up here and why.

Disheartened yet ambitious, I thought it would be fascinating to write my undergraduate thesis on Sylvia Plath’s poem “Daddy.” I was prepared to have my best year yet, immersed in a project I thought would not be tainted by the ideological bent I’d identified in the teachings of my professors.

Several weeks later, the department emailed me to call out my misogyny. My thesis would have challenged the feminist scholarship that enshrines Plath’s work, so of course I could not write it—and, by this time, I was too disheartened to come up with a proper response. Barred from the undergraduate thesis program, I enrolled in a masters program at Columbia in preparation for my upcoming PhD application cycle, but the environment remained the same: literature was open to interpretation, but only if the interpretation said something clever about oppression, societal injustice, or gender theory. I had figured out the themes I needed to use to succeed in literary study, but I was no longer studying literature.

Shortly after, I decided not to pursue a PhD.

It turned out that there were others who were similarly put off by this restrictive approach to literature. A fellow classmate, for instance, notoriously pushed back in The Columbia Spectator on a group of students’ call to dampen the Western focus of a core class called “The Masterpieces of Western Literature.” That earned a letter in response, also in The Spectator, claiming that the core curriculum “is indoctrination into white supremacy.” Instances like this demonstrate the power of a small yet vocal group of ideologues in the literary academy who seek to eradicate all viewpoints other than their own.

It turned out that my high school math teacher was onto something. There is something wrong with people who study English—and I have since figured out that this is because they somehow never realize that they’re not actually studying literature. While I do not advocate for the complete erasure of literary theory from the academy, I believe that university English departments have drifted too far to one side and often invoke voices that have no place in literary study.

The purpose of literature is not to comment on the political dimension of a given social structure or to use language as a means of fighting for justice. Literature is a different activity. Its purpose is to offer universal observations about human nature.

As academics across American college campuses continue to remove true literary scholarship from their programs, maybe it’s time for the rest of us to pick up a great work of literature and renew our allegiance to the humanistic tradition.

In the meantime, I’m proud to say I’m not a PhD.

Liza Libes founded her literary project, Pens and Poison, in New York City. Her writing has most recently appeared in The Hechinger Report, The American Spectator, and Minding the Campus.

Follow Persuasion on X, LinkedIn, and YouTube to keep up with our latest articles, podcasts, and events, as well as updates from excellent writers across our network.

And, to receive pieces like this in your inbox and support our work, subscribe below: