272 Words That Changed America

What we talk about when we talk about the Gettysburg Address.

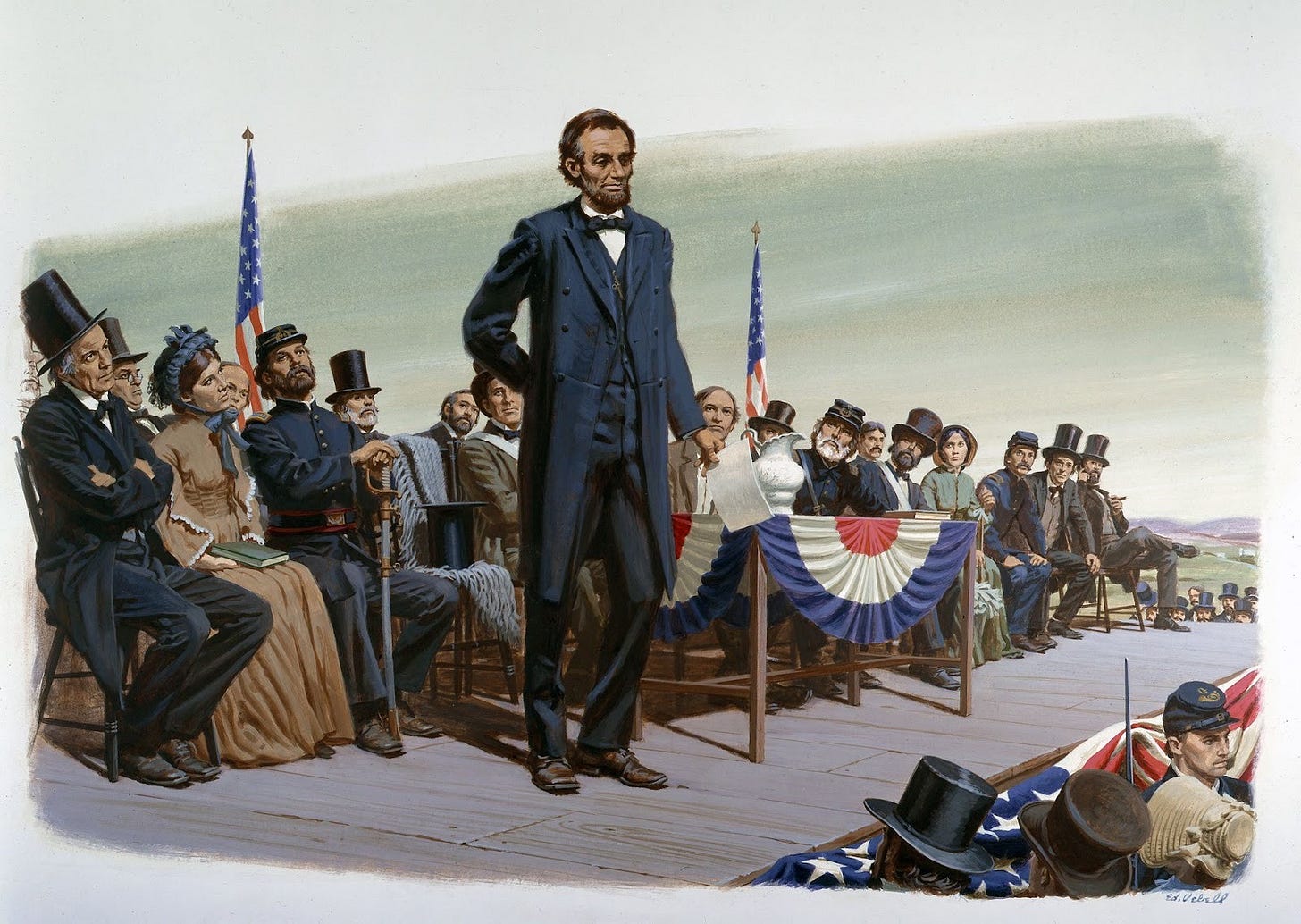

On November 19, 1863—exactly 162 years ago today—Abraham Lincoln delivered the most famous speech in American oratory.

The Gettysburg Address was given at the commemoration of a new national cemetery to mark the battle of Gettysburg that had occurred some four months before. The main speaker of the day was the Reverend Edward Everett; Lincoln was invited at the last minute and asked to perform “the last solemn act of dedication.” Everett’s speech lasted over two hours; Lincoln’s under three minutes. For most of the 15,000 people who had assembled that day, Lincoln’s speech was over before it began, yet in 272 words he accomplished nothing less than the creation of American democracy.

It is an urban legend that Lincoln’s speech was written on the back of an envelope on the train journey up to Gettysburg. This is false, but in America, as the saying goes, when the legend becomes fact, print the legend. He continued to refine the text during the trip, but we know that he took extraordinary care in composing his speeches.

Lincoln rarely travelled during the war. Given the fact that the trip from Washington to Gettysburg was not an easy one and involved various transfers, we can infer that this was a speech he very much wanted to deliver. It was the speech that he had been preparing for his entire adult life.

The Gettysburg Address begins by reminding its audience of the date of the American founding. Lincoln places our beginning at 1776, the year of the signing of the Declaration of Independence. The famous opening, “Four score and seven years ago,” is deliberately biblical and archaic. His reference to “our fathers” is intended to recall the biblical patriarchs who “brought forth” and “conceived” a new nation. The language of conception, birth, and rebirth runs throughout the text.

But the most striking aspect of the speech is its reformulation of the idea of equality. In a text intended to recall and honor the framers, Lincoln shows his greatest departure from them. Thomas Jefferson had declared “we hold these truths to be self-evident” that all persons are created equal. A self-evident truth is true by definition of its terms alone. The language of self-evidence comes from logic and mathematics.

For Lincoln, however, equality was a proposition to which we must remain dedicated. No one needs to be dedicated to the Pythagorean theorem—it remains true despite what people may believe—but this is not the case with a term like equality. Lincoln endows it with an existential quality that requires faith and commitment. It must undergo a trial by fire before its truth can be realized. He offers no guarantee that the proposition that all men are created equal will be proven true. Its verification depends entirely on us.

It is to this ideal that we must remain dedicated. The words “dedicate” or “dedicated” are used five times; the words “consecrate” or “consecrated” twice; and the word “devotion” twice also. The speech makes no formal recognition of theology—it mentions only once “this nation, under God”—but Lincoln’s goal is to endow the founding with a sacred beginning.

No word is more important in the Gettysburg Address than the numerous uses of the first-person plural pronoun: “we are engaged,” “we are met on a great battlefield,” “we have come to dedicate,” “we cannot dedicate,” “we cannot consecrate,” “we cannot hallow,” “it is rather for us,” “the great task remaining before us,” “we here highly resolve.” It is not “I” but “we” about whom he is speaking. We are part of a great collective noun.

But who, exactly, is this “we”? The audience at Gettysburg? The Northern dead? The soldiers in the field? All Americans both North and South? Lincoln did not use the word “democracy” in his speech, but his three-fold reference to government “of the people, by the people, for the people” gives the speech an undeniably democratic character. His goal was not simply to defend the Union and the Constitution, but to shape the principles of democratic peoplehood.

It was at Gettysburg that Lincoln transformed the struggle to preserve the Union into a struggle to create democracy. From now on, it will no longer be possible to think of the government simply as a contract between the states or even between individuals, but as a nation composed of a people with a common moral purpose without which democratic government would be impossible. Lincoln’s address is a momentous exercise in nation-building. It was at this moment that America became not a collection of states or a mass of individuals, but a people.

The Gettysburg Address begins with a reference to “this continent”—the land and the soil—but it concludes with a reference to the “earth,” suggesting that the struggle for democracy is not just an American phenomenon but something that will affect the future of mankind. The speech reveals an upward trajectory from the particular to the universal. The war may have begun as a purely sectional conflict between North and South, but it has become part of a global struggle for democracy.

Lincoln’s promise of “a new birth of freedom”—a startlingly ambitious phrase, almost a revolutionary one—announced his attempt to endow democracy with a new beginning, purified from the stain of slavery and rooted in respect for the dignity of every human being. It was Lincoln who gave to democracy the uniquely aspirational meaning that we attribute to it today. When we speak of democracy, we do so in the language that Lincoln created.

Steven B. Smith is the Alfred Cowles Professor of Political Science at Yale where he teaches political theory.

Follow Persuasion on X, Instagram, LinkedIn, and YouTube to keep up with our latest articles, podcasts, and events, as well as updates from excellent writers across our network.

And, to receive pieces like this in your inbox and support our work, subscribe below:

I spent the last 19 years of my teaching career teaching American history at an independent elementary school in NYC. The school had a Grandparents Day in April, and every year I would use that day for a discussion of Lincoln’s address with the kids and their grandparents, even the day that one of the grandparents was a published expert on Lincoln (although I had my heart in my throat the whole time).

In preparation, I would always ask the kids to be able to tell me as well as they could what was in the address, and what, that they might have expected to be, was not. And I always asked for volunteers to read it at the beginning of the class (in all honesty that was not because I wouldn’t have preferred to do it myself, but because I knew I would not be able to get through it without choking up).

The thing I always wanted the kids to notice was that although he was speaking as the Commander in Chief of the victorious Union army, Lincoln never referred to North or South. He never did what most who came to hear Everett (and Lincoln if they were aware that he was coming) would have expected, the leader of the winning army extolling his side’s victory.

What I was always hoping for, but did not always get, was some kid seeing what Dr. Smith notes, that this was not a coach praising his team, but the President of all Americans describing a very loud, very violent argument (which is, of course want war is) to decide what American was going to be.

Finally, I would ask them who Lincoln was talking to. And there was always at least one who replied something like, “Us, through all the ages to come”.

This is a superb reflection. Thank you.