A Deal with Three-fifths of a Devil

Was the U.S. Constitution’s “three-fifths” clause a treacherous accommodation of evil or a ploy to end slavery? The truth lies in between.

Given events of the past year—like the police shootings of Black Americans, the debate over whether the United States is systemically racist, and the New York Times’ 1619 Project— it’s no surprise that attention would eventually turn to the question of how the U.S. Constitution handled the matter of slavery.

Many today regard the Constitution the way the American abolitionists of the 1830–60s did: as a deal with the devil that legitimized a practice as immoral as any imaginable. Just last week a Tennessee legislator, in a debate over the teaching of slavery in the state’s schools, argued that the Constitution’s Article I, Section Two, counting each slave as three-fifths of a person for purposes of federal taxes and congressional representation, was actually meant to help end slavery. It seems the Tennessee legislator meant that the clause gave each state an incentive to free its slaves so that it could count each one as a whole person for representation purposes. On the other hand, the same manumission could make the state liable for more federal taxes; so, the side of the balance on which the three-fifths provision would have counted is not at all clear.

In any event, reaction to the Tennessee legislator’s comments was swift and fierce. His critics said his argument was historically, demonstrably false: Rather than being an anti-slavery provision, the three-fifths clause reflected the Founding generation’s view that slaves were not fully human.

In fact, the issue of how to read the three-fifths clause is more complicated than either side has made it.

The three-fifths fraction was originally intended to reflect not a dehumanizing calculation of how much less of a person a slave might be, but, rather, the level of productivity or wealth that could be expected to result from slave labor. The Continental Congress was trying to find some formula by which the federal government could tax the states to support the Revolutionary War. A state’s population was thought to be a plausible surrogate for its wealth. Southern states argued that slave labor was only half as productive as free labor. Northern states said slave labor should be judged two-thirds as productive as free labor. The three-fifths figure was a compromise, and the whole debate showed a consensus that free labor was more valuable than slave labor. That was why a free Black, as opposed to a slave, was to be counted as a whole, single person.

The actual text of the three-fifths clause does not even use the world “slaves:”

Representatives and direct Taxes shall be apportioned among the several States which may be included within this Union, according to their respective Numbers, which shall be determined by adding to the whole Number of free Persons … three fifths of all other Persons.

This formulation certainly reflects hypocrisy on the part of the Constitution’s drafters but also acknowledges the foundational fact that even slaves are “persons.” The Framers expected that, in time, slavery would disappear, as it had already started to do in the North in the wake of the Revolution. They did not want to stain the Constitution with the term “slavery” or “slave,” nor would they grant those terms added legitimacy by making them part of that foundational text. Indeed, the first major policy act under the new Constitution was to ban slavery from the recently acquired Northwest Territory.

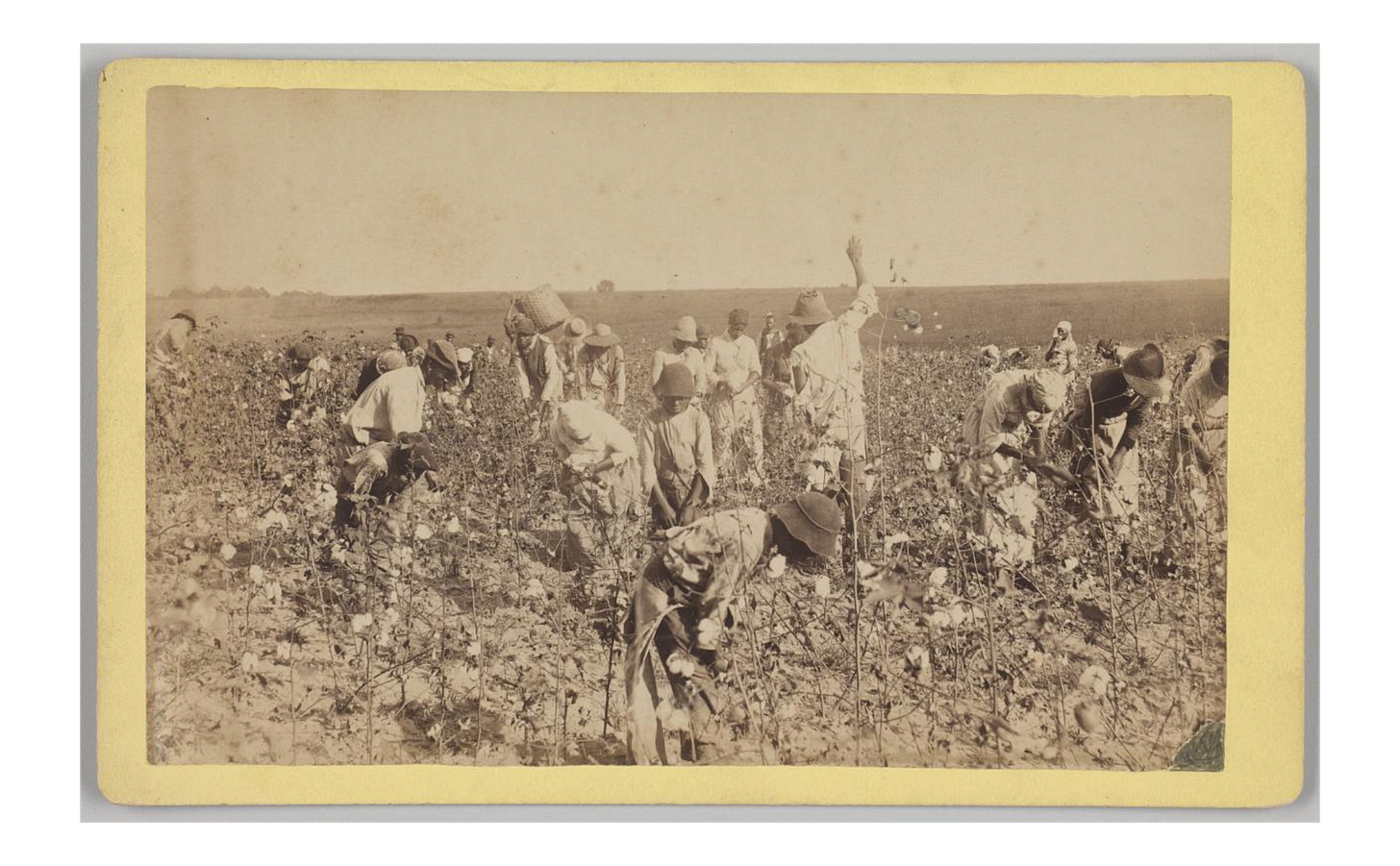

Nonetheless, the Founders’ decisions left the door open for the continuation of slavery in the states. Under Article I, Section Nine, Congress was prohibited from ending the importation of slaves for twenty years. When the twenty years had passed, Congress did ban the transnational slave trade; but by that time, the invention of the cotton gin and the expanding cotton trade with Great Britain had strengthened slavery’s place in the South’s agricultural landscape. The end of slavery would come only after another half century—and only by force of arms.

The reasoning behind the Founders’ decision to compromise on slavery was, as Michael Zuckert noted in the American Enterprise Institute’s 2013 Walter Berns Constitution Day Lecture, “in accord with, and in a way required by, the nature of the task of union-making as they understood it and by the two chief principles of federalism and republicanism.” That is, it was a compromise with an existing evil—but not without principled ends and reasons for undertaking it. One can certainly argue that the decision turned out to be flawed. Without that compromise, though, no Union was possible; and, without the Union, slavery’s extinction would have been even less likely.

There is no question that slavery is America’s “original sin,” for which the country has continued to pay. But it would be wrong to think that the Founders didn’t recognize it as such—and that they didn’t believe that the Constitution’s accommodation to slavery ran against the principles of equality, liberty, and consent put forward in the Declaration of Independence. Getting the history right does not whitewash the Framers’ decision. Rather, it recognizes that circumstances, principles, and prudence are not easily reconciled—and that even well-intentioned plans do not always succeed.

Gary J. Schmitt, a contributing editor of American Purpose, is a resident scholar in strategic studies and American institutions at the American Enterprise Institute.