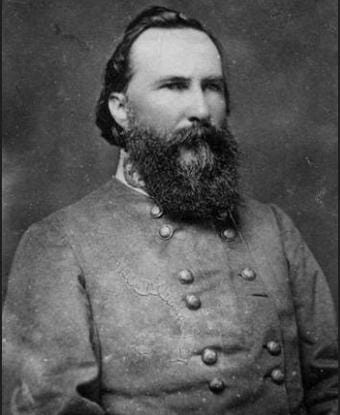

One of the greatest military leaders to emerge during the Civil War was Confederate General James “Pete” Longstreet, one of Robert E. Lee’s corps commanders who participated in many of the decisive campaigns through the end of the war. On the climactic third day of the Battle of Gettysburg in July 1863, Lee ordered Longstreet to attack the Union center. Longstreet disagreed with Lee’s order, which he believed would lead to a slaughter, but he felt obliged to obey and was proven disastrously right. His lead division under Gen. George Pickett launched its famous “Pickett’s Charge” against a heavily fortified Union position and lost more than 60 percent of its manpower in a single afternoon; all thirteen of Pickett’s colonels were either killed or wounded that day. Gettysburg was, of course, the pivotal battle of the war that foreshadowed the South’s eventual defeat in 1865.

Longstreet’s military genius lay in his recognition that the repeating rifle had shifted the advantage decisively to the defense, and that military strategy therefore needed to be built around this insight. Previously, infantrymen armed with muskets would require precious seconds to reload their single-shot weapons; the new rifles allowed them to get off several rounds before reloading. Longstreet calculated that a soldier dug into a good defensive position could shoot four or five attackers charging over open ground before the latter could get off a single shot. Foreshadowing B. H. Liddell Hart’s “indirect approach,” Longstreet argued that armies henceforth needed to maneuver themselves into strong defensive positions and force the enemy to attack them. This is why, after the Confederate successes on the first day of Gettysburg, he pushed for withdrawing back behind George Meade’s Union Army and positioning the Army of Northern Virginia between it and Washington, D.C. Had Lee followed Longstreet’s advice, the Confederacy might have won the Civil War that summer.

___STEADY_PAYWALL___

Many military historians have noted that Longstreet was more than fifty years ahead of his time, and that his ideas should have guided strategy during the First World War. By that time, the repeating rifle had been supplemented by the machine gun; the horrendous casualties of the later conflict were caused by generals who, like Robert E. Lee, insisted on sending soldiers “over the top” to assault fortified defensive positions. As in the American Civil War, it was not unusual for the warring sides to suffer multiple tens of thousands of casualties after a few days of battle. The defensive stalemate that emerged in 1914 was broken only with the invention of the tank, which allowed the attacker to maneuver quickly and get behind entrenched defenses.

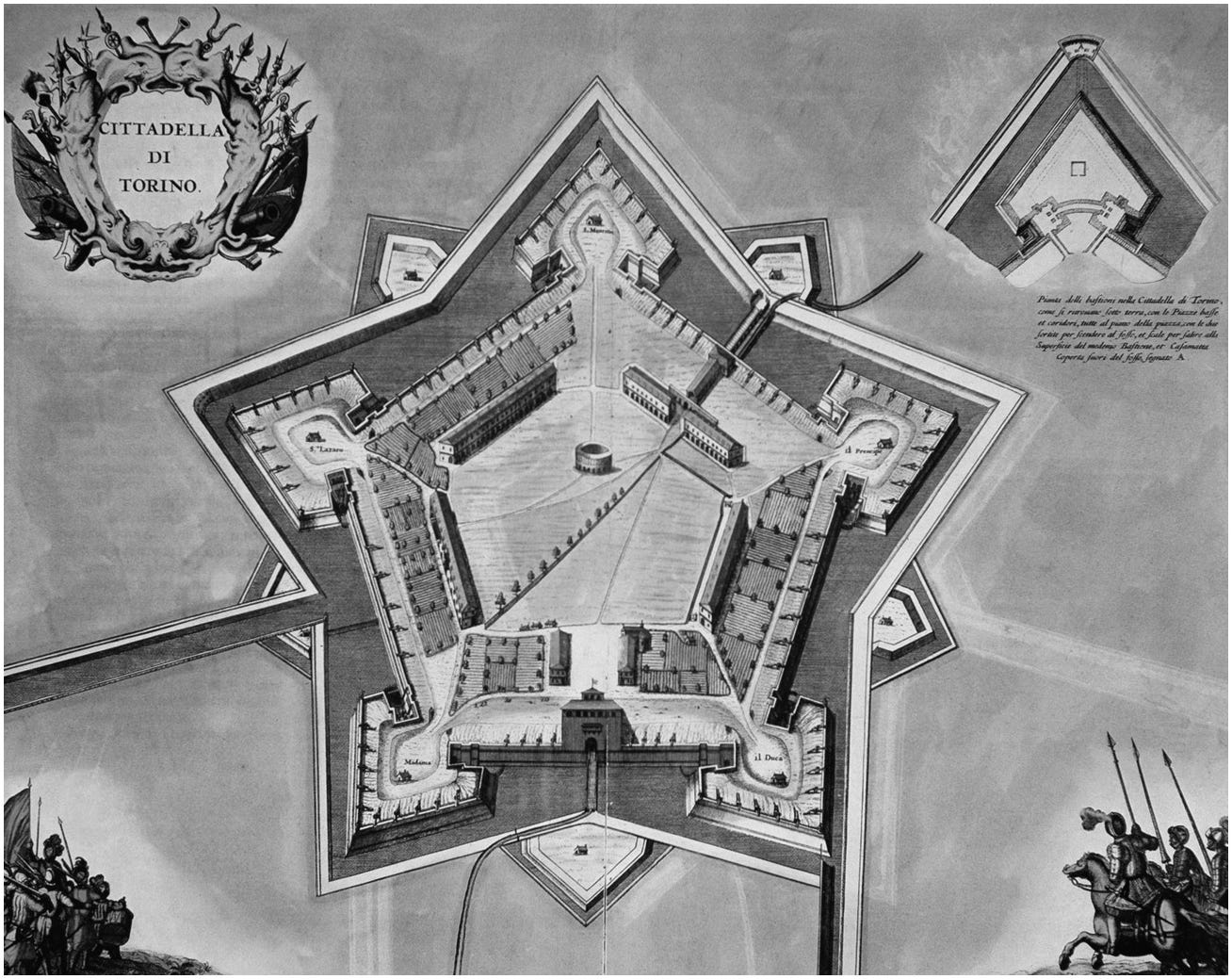

This is not the first time that changes in technology have rapidly shifted the balance between attackers and defenders. The invention of the stirrup enhanced the mobility of cavalry; this offensive advantage subjected settled agrarian societies in Europe, China, and the Middle East to repeated incursions by horse-mounted nomadic peoples. This centuries-long period in human history came to an end only with the development of artillery, which shifted the advantage back to the defense. Defensive advantages continued to mount: the trace italienne was a star-shaped fortress that allowed defenders to pour enfilading fire on an opponent seeking to breach its walls. Such forts spread rapidly throughout Europe in the 16th century, and allowed the Netherlands’ United Provinces to resist conquest by the Hapsburg emperor over a seventy-year period.

More than 100 years after its development, we are still living in the age of the tank. The armies of NATO and the Warsaw Pact, and today’s NATO and Russian forces, are still built around combined-arms units whose most important weapon remains the main battle tank. The tank has held sway for this extended period of time because, up until the past few decades, the only weapon that could destroy a tank was another tank. During the Six-Day War in 1967, the dominant Israeli Air Force was able to destroy only a small handful of Arab tanks; the rest had to be taken out by Israel’s armored forces.

All of this began to change in the last years of the Vietnam War, as the United States began to deploy precision-guided weapons, using a variety of technologies like electro-optical, laser, radar, and GPS guidance systems. A tank’s armor protects it only from lateral and indirect fire; it is vulnerable if hit directly from above. The United States developed a series of precision-guided weapons like the Maverick and Hellfire missiles, or the Joint Direct Attack Munition (JDAM) that could be strapped to a variety of “dumb” bombs. These were accurate enough to hit individual vehicles from the air, and were used extensively during the two Gulf wars and in Afghanistan.

Effective as these weapons were, they still had to be delivered by airplanes, which were expensive, limited in range, and piloted by human beings who could be killed or captured. This didn’t matter in the recent Afghan and Iraq conflicts, since the United States enjoyed total air superiority and could operate with impunity. But this condition would change dramatically in a conventional conflict with a “peer competitor” like Russia or China.

This is where armed drones have the ability to be complete game-changers. Drones are relatively cheap, don’t require pilots onboard, and at the moment cannot be easily taken out by existing air defense systems. Fifteen years ago, it was only the United States and Israel that deployed such weapons; today, as I wrote last week, a wide variety of less technologically advanced countries and terrorist groups, from Turkey to Iran to Ethiopia and the Taliban and Hezbollah, have deployed them.

It seems possible that military drones will shift the overall advantage back from offense to defense by ending the hundred-year dominance of the tank. In recent conflicts, drones have been used to destroy tanks, trucks, artillery pieces, and virtually everything else that can be located from the air. Such targets can be hidden or hardened, but the moment they get out on the road they are vulnerable. The effectiveness of a combined arms force, of course, depends crucially on its mobility, and it is this that is proving most vulnerable. By contrast, drones are of limited use as offensive weapons, since they cannot be used by themselves to hold territory.

This would not be the first time that a new technology has led to the block obsolescence of an existing weapons system. The launching of the Dreadnought forced all early 20th century navies to replace their existing battleships, while the aircraft carrier ended the reign of the battleship. (Aircraft carriers, by the way, have themselves been obsolete for some decades now as a result of missile technology and submarines; it’s just that they haven’t been used against a peer competitor since the Second World War.)

How military drone technology will play out in the future is of course uncertain. There may be a sudden technological breakthrough in defeating drones, or they may be incorporated into offensive units in novel ways. Past historical experience suggests, however, that existing powers with big investments in legacy technologies like tanks will resist the rapid exploitation of newer ones. It is therefore not a surprise that drones are today being fielded asymmetrically by smaller countries and sub-state actors without a huge stake in the status quo.

James Longstreet, by the way, had an interesting career after the Civil War. He joined the Republican Party and worked with his former antagonist Ulysses S. Grant during Reconstruction. Longstreet led an African-American militia against the paramilitary White League in the 1874 Battle of Liberty Place, following a contested election in New Orleans. These actions destroyed his reputation in the South, which is why there is a Fort Hood and a Fort Bragg today, but no Fort Longstreet. In the South he was widely blamed for the defeat at Gettysburg, and only in the 20th century has his prescience as a military theorist been adequately recognized.