This article is brought to you by American Purpose, the magazine and community founded by Francis Fukuyama in 2020, which is now proudly part of the Persuasion family.

by Joseph Horowitz

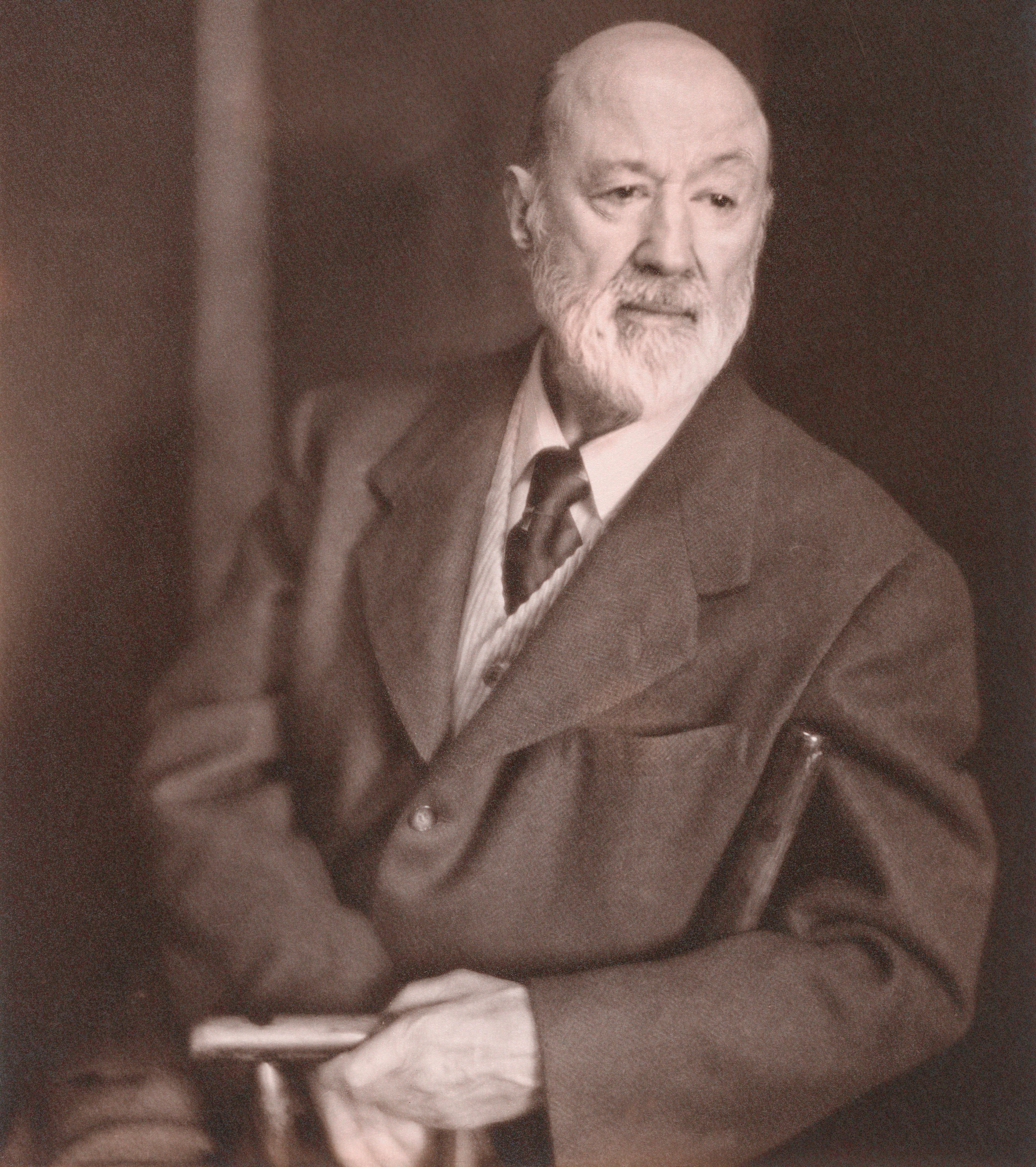

The Civil War historian Allen Guelzo, who also knows music, likens the composer Charles Ives (1874-1954) to Abraham Lincoln. “They share a capacity to inhabit American history. And they rallied people—in their different spheres of government and the arts—to participate in that, and to discover common roots.”

The 89-year-old pianist Gilbert Kalish, who made landmark Ives recordings half a century ago, laments that Ives is today more performed and appreciated in Europe than in the United States. He calls that “an American tragedy.”

My film Charles Ives’s America has just been released on Naxos’ YouTube channel to mark the Ives Sesquicentenary. It argues for Ives as a seminal American.

Of the crises today afflicting the fractured American experience, the least acknowledged and understood is an erosion of the American arts correlating with eroding cultural memory. Never before have Americans elected a president as divorced from historical awareness as Donald Trump. If Ives is the supreme creative genius of American classical music, it’s partly because, more than any other American composer of symphonies and sonatas, he is a custodian of the American past. A product of Danbury, a self-made Connecticut Yankee, he created a bracing New World idiom steeped in the New England Transcendentalists, in the Civil War, in smalltown patriotic celebrations. His improvisatory bravado, espousing the “unfinished,” equally links to such ragged literary icons as Mark Twain, Herman Melville, and Walt Whitman.

Ives’s father led a celebrated Civil War military band. Later, as Danbury’s pre-eminent bandmaster, George Ives also led the singing at religious camp meetings. Charlie played in George’s band. And, from the age of 14, he played the organ professionally in church. The honesty of the hymn-singing he heard growing up—a cherished memory—seals the fervor of his Concord Piano Sonata. The summit of American keyboard literature, it draws ferocity from Emerson and sublimity from Thoreau. In an accompanying essay, Ives writes of the Alcott House: “It seems to stand as a kind of homely but beautiful witness of Concord’s common virtue—it seems to bear a consciousness that its past is living, that the hickories of Walden are not far away … There is a commonplace beauty about Orchard House—a kind of spiritual sturdiness underlying its quaint picturesqueness.” Ives rapturously memorializes “the Scotch songs and family hymns that were sung at the end of each day.” Afloat in the Concord sky, he discerns “a strength of hope that never gives way to despair—a conviction in the power of the common soul.”

Ives’s methodology, in the Concord Sonata, is to cull a memory cloud in which the hymns and songs of his childhood, the camp meetings and Main Street parades, are subtly and subliminally gleaned. He does not, like Aaron Copland or Virgil Thomson, overtly quote the tunes he cites. Though ingeniously plotted, his compositional strategy suggests spontaneity and improvisation. The persistence of memory in Ives, its absolute ubiquity, also connotes exigency. He is in fact negotiating a transitional fin-de-siecle moment during which American lives were challenged by new technology, and by a decline in the authority of religion and other sources of moral authority. It is an exercise that resonates mightily today.

“Ives fills a great blank for contemporary Americans,” says Guelzo. “We exist in an environment that is so immediate, that is so rootless, which lacks so much in the way of cultural ballast, that we sometimes feel like we’re floating weightlessly. In that respect we live downstream from the cultural shift that occurred in Ives’s lifetime. And Ives responds to it by providing ballast in the form of experience. It’s different from the way other American composers have gone about that. They invoke the past in an almost decorative fashion. It’s like walking into an antique store. That’s not Ives.”

One of the pieces explored in the film “Charles Ives’s America” is the first of Ives’s Three Places in New England: “The ‘St. Gaudens’ in Boston Common” (1915-17). His topic is the famous 1897 bas-relief by Augustus Saint-Gaudens depicting Colonel Robert Gould Shaw and his Black Civil War regiment, with its imagery of proud Black faces and striding Black bodies. Shaw and many of his men perished in an ill-fated assault on Fort Wagner in Charleston, South Carolina. Ives’s response is a ghost dirge—music barely tangible—suffused with weary echoes of Civil War songs, work songs, plantation songs, church songs, minstrel songs. Its hypnotic tread evokes stoic fortitude—out of which arises, as Ives puts it in an accompanying poem, “the drumbeat of the common heart.”

In one of his many sui generis songs, Ives sets the words (his own) “I think there must be a place in the soul all made of tunes.” He also once said: “I sort of hate all music … I hear something else!” His “St. Gaudens” moves inside its ubiquitous tunes. An homage to enslaved lives become American lives, it’s not just perennially pertinent; it remains, literally, new: incomparable. It’s also, more than ever, challenging for audiences. Peter Bogdanoff, who created the visual track for the Naxos “Charles Ives’s America” film, renders a visualization of Ives’s score, incorporating both Saint-Gaudens’ sculpture and photographs of Shaw’s soldiers. He has since created a visual treatment for the entirety of Ives’s New England triptych, which premiered at an Indiana University Ives festival last month. It will next be seen when the Chicago Sinfonietta pays tribute to Ives on February 22.

An ideal starting point for newcomers is an earlier, more traditional work: the Symphony No. 2, completed in 1909. This is a Romantic patriotic canvas without a single original tune. Like Mark Twain’s Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, it tweaks a hallowed Old World genre by feasting on New World vernacular expression. Its Civil War finale achieves a lyric pinnacle by distilling Stephen Foster’s “Old Black Joe” (which is not a blackface minstrel song sung in dialect, but an empathetic parlor song here deployed, as Ives once put it, to express “sympathy for the slaves”). Not until 1951 was Ives’s Second premiered—by Leonard Bernstein and the New York Philharmonic, to an 11-minute standing ovation. Ives, in Connecticut, listened to it on a neighbor’s radio—after which he spat in the fireplace and walked home.

Joseph Horowitz is the author of thirteen books exploring the American musical experience. His “More than Music” documentaries, including a forthcoming Ives tribute, are heard on National Public Radio.

Charles Ives’s America:

“…very likely the most important film ever made about American music … It moves Ives from the fringes squarely to his position as the seminal composer of our country.”

- JoAnn Falletta, Music Director, the Buffalo Philharmonic

Follow Persuasion on X, LinkedIn, and YouTube to keep up with our latest articles, podcasts, and events, as well as updates from excellent writers across our network.

And, to receive pieces like this in your inbox and support our work, subscribe below: