Anatomy of a Blunder

NATO expansion redivided Europe, isolated Ukraine, and enabled Vladimir Putin.

In the first month of 2022, Russia, under the leadership of Vladimir Putin, presents a grave threat to European security and American international interests. It has a hundred thousand troops on or near its border with Ukraine and has threatened a full-scale invasion unless the Atlantic Alliance, NATO, accepts a series of demands that the Alliance has rightly rejected. Or rather, Russia is threatening to invade Ukraine again, having already seized the Crimean Peninsula and placed forces in eastern Ukraine, touching off fighting that has claimed ten thousand lives since 2014.

Moreover, Russia is ever more closely aligned with China, which is working to undermine the political status quo in East Asia at the expense of the United States. In addition, Russian air power has helped Iran, the principal threat to America’s allies and American interests in the Middle East, keep its bloodthirsty client Bashar al-Assad in power in Syria.

___STEADY_PAYWALL___

Imagine, however, a different global political configuration, with Russia aligned with rather than opposed to the United States. One of the three fronts on which American forces must be ready for combat—the European one—would disappear. China would present a less formidable threat, lacking a Russian partner in pursuing geopolitical disruption. Iran would not have the Russian support it has employed in its campaign to dominate the Middle East. Russia would be using its influence to deny nuclear weapons to would-be proliferators, especially Iran. Russian cyberwarfare would not be the problem it has become.

Such a world would be far more favorable to American interests and American values than the world of January 2022. That more favorable world could have, and should have, come into being, and very likely would have done so, but for a misbegotten and disastrously counterproductive foreign policy of the Clinton administration: the eastward expansion of NATO.

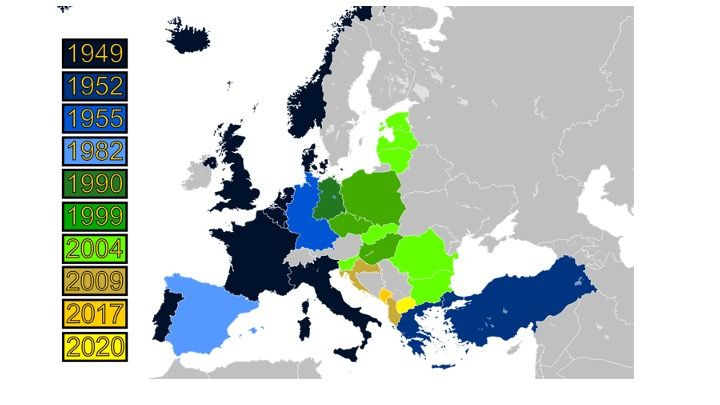

The United States expanded NATO against the deeply felt and strongly stated objections of a Russia just emerging from the seven-decades-long nightmare of Communist rule and struggling to install a democratic political system. Washington pressed ahead with expansion despite a number of assurances by Western leaders that this would not take place. It pushed the Alliance all the way to the borders of post-communist Russia while making it clear from the start that NATO was prepared to receive any country in Europe into its ranks except Russia. America expanded NATO because Russia was—temporarily, as should have been obvious—too weak to prevent it. From expansion the Russians drew some lessons that it was not remotely in the American interest for them to learn: namely, that it was vital to build up their military power, and that trust in and cooperation with the United States are foolish, if not dangerous.

One of the public rationales that the Clinton administration presented for expansion added insult to injury for the Russians. Administration officials asserted that NATO membership was needed to guarantee democratic government in the formerly communist world, despite the lack of evidence that belonging to a military organization assures democracy; during the Cold War, in fact, NATO had several undemocratic countries in its ranks. Moreover, if joining the Alliance could actually consolidate democracy, the country where membership was most important for Europe, the United States, and the world was unquestionably the one country denied it from the outset—Russia itself.

NATO expansion has had powerfully negative consequences. It alienated Russia from the West, making opposition to Western and especially American preferences and initiatives the default mode of Russian foreign policy. It undercut the prospects for a post-Cold War Europe that was “whole and free,” to use an American term, by drawing a new line of division on the continent with NATO members on one side and countries without membership, notably newly independent Ukraine, on the other. It led, ultimately, to the resumption of the political and military rivalry characteristic of Cold War Europe, and of most previous European history, that the end of the Cold War had afforded an unprecedented opportunity to transcend. It ranks, therefore, as one of the greatest blunders in the history of American foreign policy.

Not One Inch: America, Russia, and the Making of the Post-Cold War Stalemate (2021) by M.E. Sarotte, the Kravis Distinguished Professor of Historical Studies at the Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies, recounts the sequence of decisions, especially within the American government, that produced NATO expansion. It builds on the author’s previous books about the end of the Cold War in Europe, taking the story into the first post-Cold War decade. In part through the use of the American Freedom of Information Act, Sarotte gained access to many previously unavailable records. They help to make this gracefully written history, which bends over backward to be fair to all points of view—Russian, Eastern and Western European, and American—the most authoritative account of this historical episode that is ever likely to be written.

NATO expansion had legitimate purposes. It was intended to keep the Atlantic Alliance in business after the disappearance of the adversary it had been formed to oppose, which was a way of keeping the United States engaged in Europe in order to provide a measure of stability to that often war-torn continent. Expansion was also designed to reassure the countries of Eastern Europe and the non-Russian former republics of the Soviet Union that had achieved independence with the Soviet collapse in December 1991 that they were not fated to exist in a strategic vacuum, at the mercy of a reduced but still powerful Russia if that country should adopt a revanchist foreign policy.

As is clear from Not One Inch, however, the United States could have achieved these goals without paying the high price that NATO expansion exacted, by persisting with an organization that America created at the beginning of 1994 called the Partnership for Peace (PfP). That organization was open to all countries in Europe, and many participated. It involved military cooperation of various kinds. Participation did not preclude NATO membership, but neither did PfP establish a fixed timetable for formally expanding the Alliance or exclude eventual Russian membership. It thus provided time to judge the political trajectory of the new Russia before taking steps that were bound to worsen relations with Moscow. The Department of Defense welcomed PfP. Russia’s democratically-inclined President Boris Yeltsin, already worried about NATO expansion, called it “brilliant” and “a great idea.” The Partnership for Peace, that is, provided the best of both worlds, preventing a security vacuum in Europe without excluding or alienating Russia. Yet the Clinton administration threw it away in favor of formal, anti-Russian expansion.

It had a variety of motives. The countries of Central Europe, especially the first three to be admitted—Poland, Hungary, and the Czech Republic—lobbied hard for full membership, and senior administration officials pressed their case. The ultimate decision rested with Bill Clinton, and he seems to have acted on the basis of domestic political considerations, seeking to win the votes of Americans with ancestral ties to these countries in the upcoming 1996 presidential election. Since it involved a treaty, expansion also had to secure a two-thirds majority in the United States Senate, and succeeded because some Senators were persuaded that the stakes were small, with no risks or costs involved, and that America was simply doing a good deed for small, friendly, would-be democratic European countries. The belief, fostered by the Clinton administration, that expansion would have no serious adverse consequences turned out to be catastrophically mistaken.

Those consequences were foreseeable in the 1990s. Indeed, they were foreseen. A group of fifty former Senators, foreign policy officials, and experts on Russia and European security signed an open letter (the present writer also signed it) calling expansion “a policy error of historic proportions.” George F. Kennan, the former American diplomat who first prescribed the post-1945 policy of containment toward the Soviet Union, termed expansion “the most fateful error of the entire post-Cold War period.” Clinton’s secretary of defense, William Perry, opposed the measure so strongly that he seriously considered resigning over it. The Clinton expansionists charged ahead with their project anyway.

An aggressive, anti-Western foreign policy is not the only damaging Russian trend of the last two decades. Putin, Yeltsin’s successor as Russia’s president, reversed the shaky progress toward democracy that the country had made in the 1990s. Post-communist Russia has become a dictatorship. NATO expansion did not, by itself, determine the course of Russian domestic affairs. Russia’s historical absence of democratic traditions, experience, and institutions would have made democracy-building difficult whatever the United States did or refrained from doing.

Still, expanding the Alliance while excluding Russia certainly did not help matters. It undercut the country’s beleaguered democrats, who had identified themselves with the West. Even worse, Putin has used what he has claimed to be the threat from NATO as a pretext for consolidating his power at home and for launching military adventures against Russia’s neighbors, notably the 2014 invasion and occupation of Ukraine. NATO expansion made his claim all too plausible to the Russian public, and Putin has exploited the broadly held anti-American sentiment in his country, which expansion did so much to create, to enhance his political standing at home.

Putin surely knows that NATO is not about to attack Russia, but he also knows that to maintain his grip on power he needs at least a modicum of popularity and that posing as the defender of a beleaguered nation is the source of public esteem most readily available to him. Post-Soviet Russia would have presented difficulties to Europe and the United States under any circumstances, but it would have been far better, to paraphrase President Lyndon B. Johnson, to have the Russians inside the tent spitting out than outside the tent spitting in. (Johnson referred to a different bodily function.) NATO expansion fecklessly evicted them from the tent.

The decisions that Sarotte ably chronicles belong to the ever receding past, but they have a significance that transcends the purely historical. Vladimir Putin’s policies rule out cordial Western relations with Russia as long as he remains in power. Today the appropriate policy toward Russia is deterrence, not conciliation. One day, however, he will be gone. Who and what will succeed him cannot be known in advance, but it is possible that a new leadership will wish to repair relations with Russia’s neighbors, the West, and the United States. In such circumstances it will be crucial for policymakers to understand the great mistakes of the past in dealing with Russia, in order to avoid repeating them.

Michael Mandelbaum is the Christian A. Herter Professor Emeritus of American Foreign Policy at the Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies, a member of the editorial board of American Purpose, and author of a forthcoming history of American foreign policy, The Four Ages of American Foreign Policy: Weak Power, Great Power, Superpower, Hyperpower, which will be published in June.