Conservatism, Once and Future

In their new books, Matthew Continetti illuminates while Yoram Hazony stumbles.

The Right: The Hundred Year War for American Conservatism

by Matthew Continetti (Basic Books, 496 pp., $32)

Conservatism: A Rediscovery

by Yoram Hazony (Regnery Gateway, 256 pp., $29.99)

It is Republican primary season, and talk of a GOP civil war once more fills the air. The idea is overstated: Donald Trump’s influence on Republican voters is going strong. But the conservative movement is still searching for an alternative to Reaganism, and two new books offer useful insights on the quest.

The first is Matthew Continetti’s The Right, a history of the past century of conservative thought and right-of-center American politics.

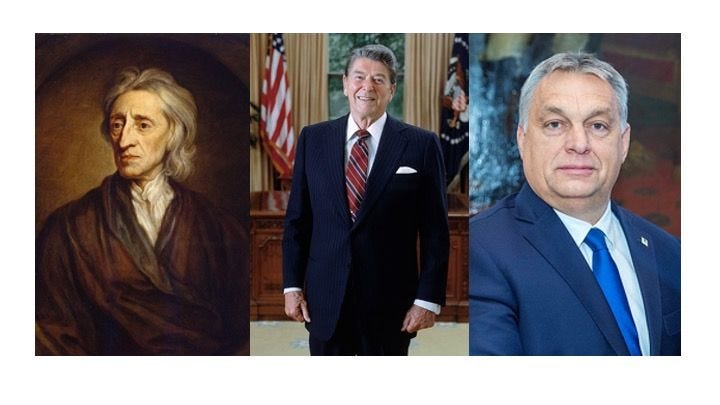

This is a complicated story. As Continetti notes, “There is not one American Right; there are several.” One of his prominent themes lies in the ongoing efforts by intellectuals and political leaders to address American populism. Another is the battle between Lockean liberals and European-style, traditional conservatives for leadership of the conservative movement.

Continetti starts with Warren Harding’s 1920 election. After eight years of Woodrow Wilson’s progressive upheaval, Americans were certainly ready for Harding’s promised “return to normalcy.” Harding and his successor, Calvin Coolidge, endorsed traditional American conservatism: fidelity to the Constitution and the Declaration of Independence, low immigration, high tariffs, Christian patriotism. The 1920s were a period of American revival and prosperity—until the great stock market crash.

Huey Long and Father Coughlin emerged as the Great Depression’s most notorious figures. Long was an iconic Southern populist; his economic policy was far to the left of the New Deal, and he ruthlessly suppressed his political opposition until he was killed in a shootout between an assassin and his numerous bodyguards. Father Coughlin, a Michigan antisemite, attacked Roosevelt from the left, accusing him of being a tool of Wall Street. Roosevelt retaliated, using the Federal Communications Commission and other agencies to cripple Coughlin’s radio program and stop mail delivery of his magazine Social Justice.

Long and Coughlin illustrate the challenge faced by every historian: to depict historical figures in their own terms while also contextualizing them for readers. Continetti includes Long and Coughlin in his history—but they stood well to the left of Roosevelt. In Southern politics, the remaining Bourbon Democrats were conservatives; populists like Long were the progressive force. Yet Southern and Midwestern populism are important parts of the American Right today, and it is nearly impossible to understand the phenomenon without reference to those two figures.

In the post-Roosevelt decades, conservatives struggled to respond to populists. William Buckley and L. Brent Bozell, Jr., endorsed Joseph McCarthy only to be embarrassed by him. Buckley’s later attacks on the conspiratorial John Birch Society had little impact, but Buckley’s quixotic mayoral campaign in New York uncovered latent blue-collar support for many aspects of conservatism; and, while George Wallace took the segregationist vote, Richard Nixon made inroads in the South.

After Nixon’s resignation, a “New Right”—single-issue advocacy groups and policy organizations like the Heritage Foundation—emerged to advance conservative policies in Washington. Many were disappointed by Ronald Reagan’s failure to achieve as many victories as had been anticipated.

When the Soviet Union imploded, the “fusionist” alliance among anti-communist hawks, traditionalists, and classical liberals did as well. It was an old fight: Bozell, who became a fascist sympathizer, and fusionist Frank Meyer battled furiously in the early pages of National Review over the value of freedom. Pat Buchanan, another fascist sympathizer, emerged as leader of the “paleoconservatives,” who in their resentment of neoconservatism often slipped into antisemitic invective.

George W. Bush’s presidency nearly severed the link between the Republicans and the populists. Despite the “humble” foreign policy and “compassionate conservatism” that took him to the White House, it became clear after September 11 that his would be a war presidency. True, the populists backed him during the invasion of Afghanistan; many continued their support into his Iraq campaign. But Bush’s attempts to reduce the appeal of jihad by building democracies in the region left them cold.

For the next decade, populists fought the conservative establishment, first by adopting the Tea Party’s folk libertarianism, then by rallying behind Donald Trump. As Continetti points out, Trump’s skepticism of trade and immigration was in some sense a throwback to the Harding-era GOP. Traditionalists have tried to seize on Trump’s energy to finally defeat the economic conservatives—but have not succeeded. Trump won the loyalty of 1970s New Right organizations by appointing Federalist Society members to the judiciary and loudly supporting Israel, which many traditionalists despise. Trump country may be red, but it loves the white and the blue. None of the branches of conservatism can plausibly claim Trump; they can only court him.

Continetti’s book is an excellent primer for understanding key aspects of the last century of American politics, and many of the author’s recommendations are very shrewd. He covers a tremendous amount of ground with lucidity and panache. At the end of his four hundred pages, he left this reader wanting more.

In Conservatism: A Rediscovery, Yoram Hazony attempts to reorient the traditionalists to this new era. As he sees it, America has erred by rejecting Anglo-American conservatism and embracing Enlightenment liberalism.

To Hazony, Anglo-American conservatives are empiricists who emphasize the nation-state, endorse public religion, embrace a strong executive checked by the people’s representatives, and defend individual freedoms granted by God. They argue that all humans are born into hierarchical communities to which they owe loyalty, strive for honor within its traditions, and through them create institutions like language, religion, law, and government, which should be altered only with great care. This tradition is much older than the Constitution; beginning in the Tudor era, a line of English thinkers prepared the ground for the Federalists. When the Federalist Party faltered, the Whigs picked up the torch of conservatism and handed it off to Abraham Lincoln’s Republicans.

Rather than emphasize the values and obligations created by specific communities, liberals believe that all people at all times in all places will embrace universal truths like the equality of man and consent-based politics. John Locke and Thomas Jefferson personify this tradition, seen most clearly in the Declaration of Independence. Hazony casts Enlightenment liberalism as a great foe of this tradition.

Hazony’s primary problem is that, whatever the merits of his argument, few if any Founding Fathers accepted it—including the ones he cites. To them, universal rights and John Locke were inseparable from their cause. George Washington told his army that “the united efforts of America are exerting in defence of the common Rights and Liberties of mankind.” Alexander Hamilton instructed an opponent of independence: “Apply yourself, without delay, to the study of the law of nature” by reading Locke and liberal authors. Before joining the Declaration’s drafting committee, Adams argued that “all men are born equal.” At the end of his life, he claimed that “mankind is most indebted” to Locke, who “most diffusively spread illumination and civilization in the world” and whose disciples

have done more to overturn tyranny civil, ecclesiastical and political, and to bring into credit & reputation principles of toleration, humanity, civilization, private judgment and free inquiry, than all the writers who preceeded [sic] them.

More, the distance between Jefferson and the Federalists is not as wide as Hazony claims. Jefferson described the Federalist Papers as “the best commentary on the principles of government which ever was written.” James Wilson—whom Hazony pegs as a traditionalist—asserted that “the people may change the constitutions whenever and however they please. This is a right, of which no positive institution can ever deprive them.” This is nearly identical to Jefferson’s thought.

Of the eight Federalist principles that Hazony describes, Jefferson more faithfully adhered to several than the Federalists and their successors did. The Federalists created a strong executive, but Henry Adams noted that President Jefferson exercised “executive authority more complete than had ever before been known in American history.” The Whig Party named itself to contrast with “King Andrew” Jackson’s executive power and attract Southern plantation owners. The Federalists, when forced to choose, put merchant bankers ahead of manufacturers. Several of the Federalists Hazony cites advocated dissolving the Union, two as early as 1794; and John Quincy Adams wrote that states-rights radical John “Calhoun is but a pupil of the Hartford Convention” that was attended by others. The closest the United States came to an actual alliance with Britain was under Jefferson, not Washington.

In some cases, Hazony’s tradition is more Jeffersonian than Federalist. He applauds the Bill of Rights, which was championed by Jefferson and opposed by the Federalists. His emphasis on hierarchy is an unwitting echo of Jefferson’s “natural aristocracy among men,” which was “the most precious gift of nature for the instruction, the trusts, and government of society.” Adams agreed that such an aristocracy existed; he wanted government to check it, not consult with it.

Many of Hazony’s conservatives saw liberalism as part of their tradition, not its enemy. Hazony asserts that Isaac Newton’s empiricism and Locke’s rationalism are fundamentally contradictory; Adams embraced aspects of both, writing to his wife that “Newton and Locke are examples of the deep sagacity which may be acquired by long habits of thinking and study.” In 1775 Washington argued that Britain’s actions were “not only repugnant to natural Right, but Subversive of the Laws & Constitution of Great Britain itself.” To Abraham Lincoln, “the primary cause of our great prosperity” is “the principle of ‘Liberty to all,’” the expression of which is the Declaration and the assertion of which

has proved an ‘apple of gold’ to us. The Union, and the Constitution, are the picture of silver, subsequently framed around it. The picture was made, not to conceal, or destroy the apple; but to adorn, and preserve it. The picture was made for the apple—not the apple for the picture.

Hazony is surely right that our political and cultural commentariat are too quick to dismiss family, faith, and tradition, and that our country has many social pathologies. But his project would uproot the sources of not our troubles but our independence. This would be a departure from our traditions, not a continuance.

“What is conservatism?” Lincoln asked. “Is it not adherence to the old and tried, against the new and untried?”

Mike Watson is associate director of Hudson Institute’s Center for the Future of Liberal Society.