David Bromwich: Milton on Censorship

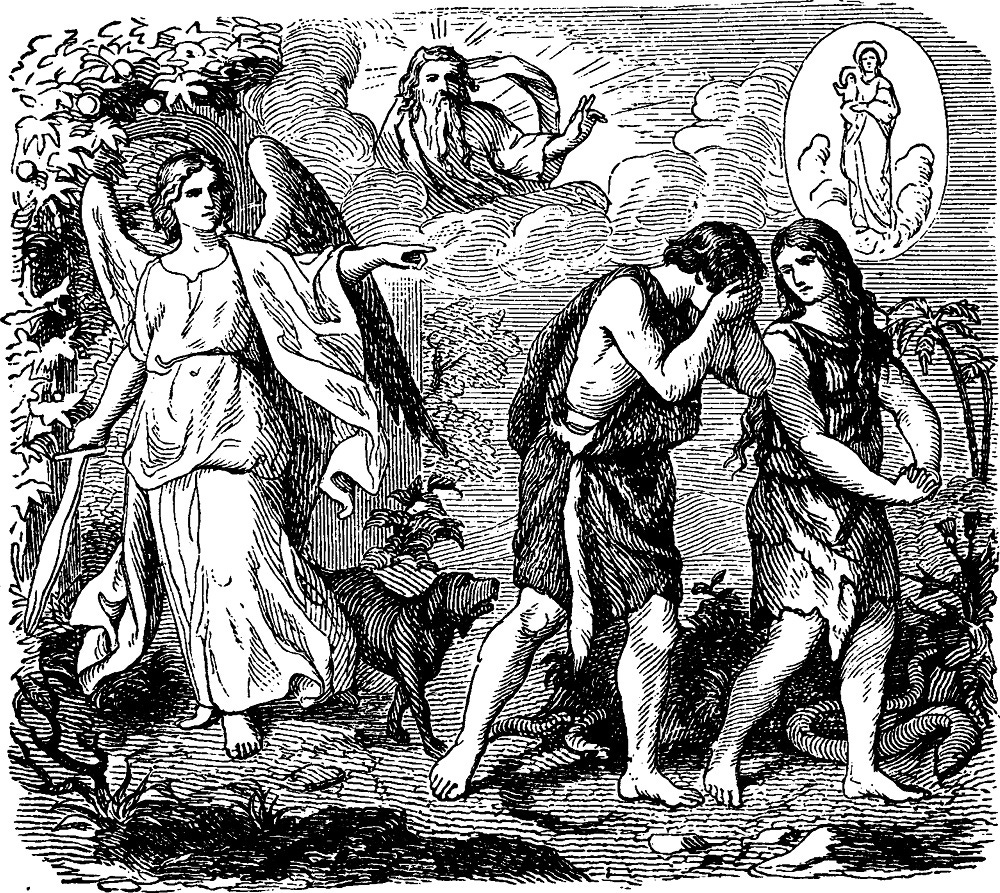

Suppressors of “harmful” speech today evoke censors of old. But tasting from the Tree of Knowledge won’t ruin us.

The blizzard of debate online makes it hard to pause and ponder like thinkers of centuries past, blessed as they were by the lack of good Wi-Fi. Maybe their writings would fail as tweets, but they still hold vital lessons. To rescue those, we’re launching an occasional feature, Persuasion Classics, where a contemporary author introduces a pertinent piece of writing from long ago. We’re delighted that our first contributor is the essayist David Bromwich, who discovered present-day insights in the work of the 17th-century author of Paradise Lost. —The Editors

By David Bromwich

John Milton wrote Areopagitica (1644) during the English Civil War to oppose the official licensing of books. His political motives can be explained simply enough—the process of licensing might have outlawed the republican propaganda he defended and wrote a good deal of himself. Yet his reasons were not merely political. The proposed censorship would have amounted to state intervention in matters of individual judgment. A free person, said Milton, should be at liberty to judge the virtue or vice of unlicensed books. Officious standards that claim to weed out writings deleterious to the public mind are a form of coercion that places state authority over personal conscience.

Today, our weeding-out encompasses much of what is sometimes described as “cancel culture”—a weak phrase for the organized effort to destroy the careers of persons who violate the most recent canons of upright verbal behavior. Examples include the firing of David Shor from a progressive consulting firm for having recommended, during the George Floyd protests, a scholarly paper showing that riots can cause political backlash; and the forced resignation of Donald McNeil from The New York Times for quoting a racial slur in answer to a question about the slur.

Areopagitica is now best known for a passage near the end:

Though all the winds of doctrine were let loose to play upon the earth, so Truth be in the field, we do injuriously by licensing and prohibiting to misdoubt her strength. Let her and falsehood grapple; who ever knew Truth put to the worse, in a free and open encounter?

This may seem hardly a conclusive argument, depending, as it does, on the belief that truth always wins out eventually. That is a faith that Milton held, as have many others. But many (then and now) have been less confident. How long is the long run implied by “eventually”? If the falsehood in question is plainly mischievous, and we are told it is gaining strength every day, can we afford to wait?

Uncertainty of the triumph of truth against falsehood, therefore, may make well-meaning politicians look for quicker remedies. This is where a second argument of Areopagitica affords a challenge to censorship on different grounds. The custodial desire to protect vulnerable readers from themselves, says Milton, is an insult to the dignity of free minds:

Good and evil we know in the field of this world grow up together almost inseparably….It was from out the rind of one apple tasted, that the knowledge of good and evil, as two twins cleaving together, leaped forth into the world. And perhaps this is that doom which Adam fell into of knowing good and evil, that is to say, of knowing good by evil….Assuredly we bring not innocence into the world, we bring impurity much rather: that which purifies is trial, and trial is by what is contrary.

Milton is saying here that innocence is not the same as virtue. Innocence, indeed, is no longer an attainable or even a desirable good, once humanity has been cast out from paradise.

We learn to know and cherish the good by testing ourselves against selfish or wrong desires, against the temptations of willfulness and vainglory, spite and cruelty—in short, against evil. Areopagitica puts the encounter with harmful words at the very heart of conscience; our progress as moral beings comes through trial “by what is contrary” to the good. “And this”—so Milton concludes his uncompromising civil-libertarian thought—“is the benefit which may be had of books promiscuously read.”

Can we believe the same is true of words promiscuously heard and tolerated? Of a speech, say, or a casual remark that might cause harm, or a diatribe that seems maliciously to intend harm? If you are a prelate or a magistrate hungry for authority over conscience, the answer must be that there is no benefit in listening. “Real words,” you will say, “do real harm”—they commit a crime distinct from, but comparable to, physical injury. And once you have granted this much, you will necessarily go back and reject Milton’s argument against censorship. It is your duty, after all, to control the stimuli experienced by promiscuous readers and listeners—people whom the wrong words might persuade to commit wrong deeds.

The censors of our own time justify themselves in slightly different language. When they seek to silence or, by slander, to discredit the speaker of words they deplore, they believe they are acting in the cause of justice and the future good of society itself. Milton’s opponents, by contrast, said they were acting in the cause of religion and parliament. But the difference is smaller than it looks. Our age has seen recurrent outbreaks of preventive mass action (with which all good citizens are supposed to agree) in order to stop books from publication. Milton’s opponents backed preventive state action (with which most citizens were supposed to agree) in order to deny a permit for publication in the first place.

In Paradise Lost, Milton’s epic of the Fall of Man—published almost three decades after Areopagitica—Eve tells Adam she has dreamed of tasting the fruit of the Tree of Knowledge; she is apparently shaken, asking if her mind was tainted by the dream, but Adam offers this comfort:

Evil into the mind of God or Man

May come and go, so unapproved, and leave

No spot or blame behind.

The Milton of Areopagitica is speaking through Adam. Dreams, on this view, are a kind of thinking in which the doors of conscious censorship are left open. The temptations a dream may disclose are part of the trial of virtue. In themselves, they no more taint the dreamer than the vicious words of a book against which a reader’s judgment may be tested.

Vagrant words (some of them possibly harmful), daydreams, half-formed hopes and fears are broadcast today with a swiftness and fecundity no poet in the age of books could have anticipated. Often, they seem to escape from their speaker with as little conscious thought as Eve put into her dream. Our cultural institutions have lately busied themselves finding new reasons for the suppression of words they consider harmful; but for the Protestant conscience that Milton wrote to defend, liberty included the freedom to test oneself with such words. Evil acts alone were to be penalized. The essentially religious theory put forward by cultural censors today—namely, that dangerous thoughts or words taint the person they have once inhabited—takes us back to the inquisitorial attitude Milton aimed to abolish.

Our watchers today are governed, if anything, by a more severe idea of moral duty than the God of Paradise Lost. Milton’s poem leads us to see that the ultimate transgression of Eve and Adam was a necessary trial for their passage from innocence to the possibility of goodness. Eve—when she finally considers eating the apple, and then does eat, and regrets doing so—becomes the first human being to have a thought. And Adam, hearing her relate the trespass, becomes the first human being to find words for grown-up love. He says he will depart with her from Eden and die with her: “How can I live without thee?”

There was a close connection between Milton’s distrust of censorship, his idea of sin, and his understanding of a sad self-knowledge that comes through the experience of human freedom. The censors of our age, on the contrary, would limit their human companionship to those who have not sinned or dreamed of sinning. These people are innocent, and they have the merciless confidence known only to the innocent. They comprise a civilian army for the purification of society.

The achievement of innocence has been a project nursed by the leaders and the soldiers of many armies, not all of them religious in the formal sense. But their important work has always required censorship as a necessary step in the progress toward purification. Non-recruits or defectors don’t imagine that they are innocent. They see themselves as probably guilty in many ways that will only be known over time. But the enforcers of morals in our age are active and energetic; they embody a church-without-walls; they crowd the pulpit and the pews, and any congregant may become preacher for a day.

In the 17th century, these people would have been petty magistrates. Today, it is hard to know what to call them. They have been described as the hall monitors of a school in perpetual session. They have been ironically called the Elect. If we keep in mind Milton’s story of the Fall and “that doom which Adam fell into,” perhaps we can see them more clearly. They are angels. They exist to assure that nobody whose words betray an evil thought will escape the deserved punishment. They patrol the gate to stop offenders from re-entering the paradise of the sinless and blameless.

David Bromwich, a frequent contributor to The London Review of Books and columnist for The Nation, is a professor of English at Yale. His most recent book is How Words Make Things Happen.

Delighted to see introduction of Persuasion Classics, at a dangerous moment in our history when such texts may disappear from university curricula. None better to begin with than Milton. David Bromwich does well to link the Areopagitica with Paradise

Lost. No “fugitive and cloistered virtue” for Milton! Felix culpa, indeed. Milton prefers freedom to Eden, and so should we all. Ignorance is not bliss even in the most PC utopia

I'm trying to imagine a world in which scholars who write about literature write about it like this. I know there are some more of you out there, but I fear the post-structuralist moral meddlers have won.