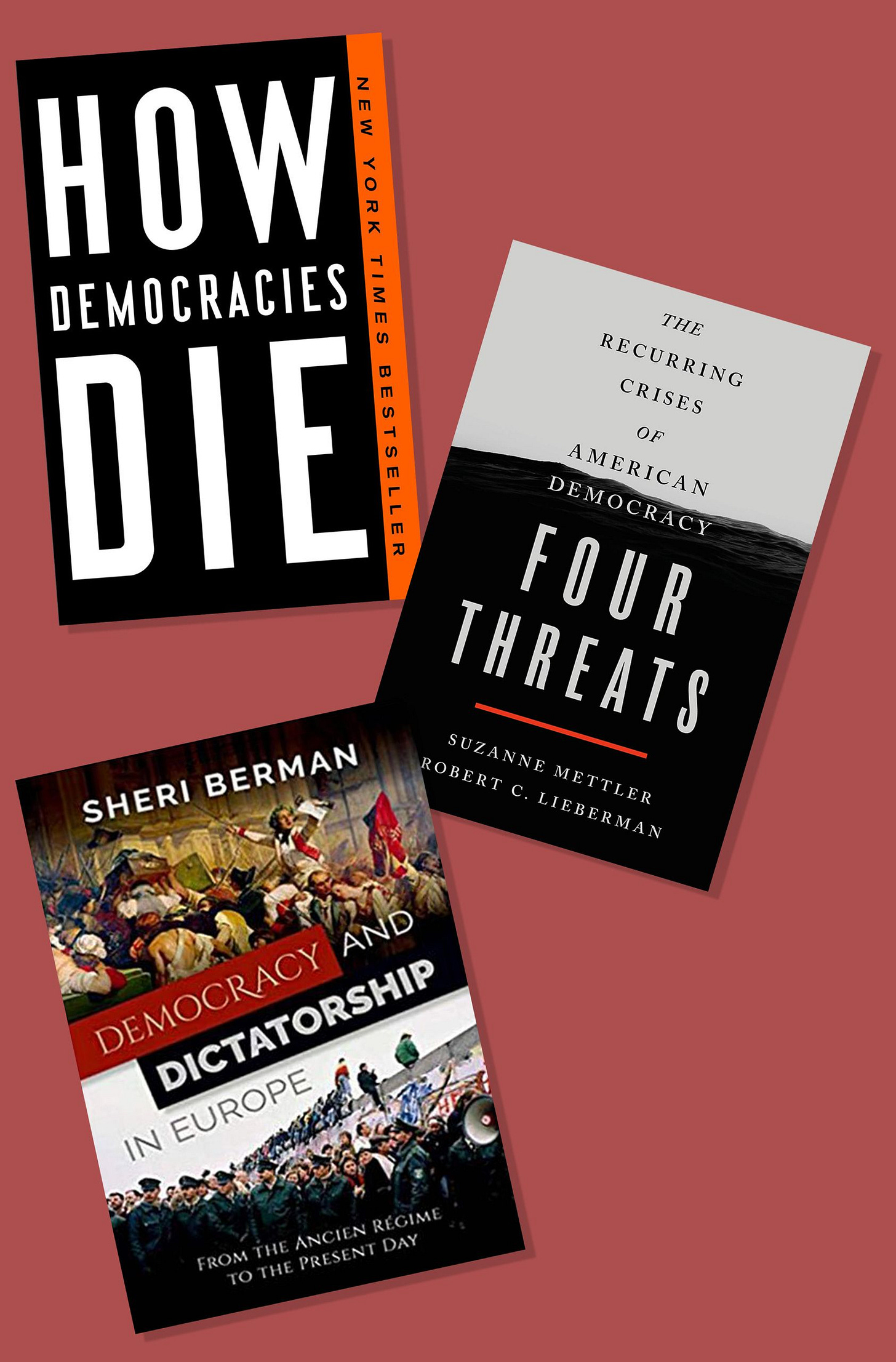

Four Threats: The Recurring Crises of American Democracy

by Suzanne Mettler and Robert C. Lieberman (St. Martin’s Press, 304 pp., $28.99)

Democracy and Dictatorship in Europe: From the Ancien Régime to the Present Day

by Sheri Berman (Oxford University Press, 560 pp., $34.95)

How Democracies Die

by Steven Levitsky and Daniel Ziblatt (Crown, 320 pp., $34.39)

If one thing is clear from the large and growing social science literature on the state of modern liberal democracy, it’s that democracy is at risk. At times, it seems to be such a mess that one is tempted to throw up one’s hands in despair.

But the past few years have produced a massive amount of excellent scholarship on democracy and its discontents, and this literature can at least provide some clarity about our predicament. The thread running through the scholarship is “democratic backsliding,” a term that has been around in political science for decades and has gained recent traction (along with more ominous words, like autocracy, fascism, and tyranny) in popular publications—Vox, the Atlantic, the Guardian.

The idea of democratic backsliding illuminates a process that’s at work in democracies today: the erosion of formal institutions, which can make it virtually impossible to hold politicians accountable, thereby eroding democracy itself. Ellen Lust and David Waldner, in a 2015 USAID white paper, described the process of democratic backsliding as comprising “changes that negatively affect competitive elections, liberties, and accountability.” Nancy Bermeo, in a 2016 article in the Journal of Democracy, defines it as a “state-led debilitation or elimination of the political institutions sustaining an existing democracy.” While many factors correlate with this sort of backsliding, Bermeo highlights two in particular. One is executive aggrandizement, which “weaken[s] checks on executive power one by one, undertaking a series of institutional changes that hamper the power of opposition forces to challenge executive preferences.” The other is strategic electoral manipulation—“actions aimed at tilting the electoral playing field in favor of incumbents.”

All these actions, Bermeo stresses, take place legally, and typically without too much outcry from citizens or even observers. Politicians can impede voter registration, attack opponents, and pack electoral commissions without ever committing fraud. These actions may be “too arcane to be the stuff of mass mobilization” or may lack “the bright spark that ignites an effective call to action.” We know that backsliding happens slowly, and that at the very least it can leave democratic publics feeling wary, distrustful, and cynical about their governments. These attitudes can have the perverse effect of making it even harder for citizens to bring about change.

Two recent books take up the question of whether democratic backsliding is occurring in the United States.

Steven Levitsky and Daniel Ziblatt’s How Democracies Die, one of Barack Obama’s favorite books of 2018, argues that democracy requires more than formal institutions and rules, like those outlined in the U.S. Constitution. Rather, democracy is a set of practices—norms—that constrain what our leaders do. These “soft guardrails” prevent political competition from breaking into open conflict. Levitsky and Ziblatt point to two guardrails in particular: mutual toleration, or respect for legitimate opposition, and institutional forbearance, the avoidance of “actions that, while respecting the letter of the law, obviously violate its spirit.”

When the soft guardrails are no longer in place, democracy can deteriorate quickly. Levitsky and Ziblatt take us through many historical examples of democracy on the brink, in places as varied as Venezuela, Hungary, Weimar Germany, and Spain. The authors describe the ways in which democratically elected autocrats take steps that “enjoy a veneer of legality . . . adopted under the guise of pursuing some legitimate—even laudable—public objective” in order to consolidate their power.

Factors that can either enable or constrain elected autocrats include political parties, public opinion, and crises. So, for instance, parties can either contain a leader or, through silence and complicity, provide him with even greater power. (For a deeper look at such complicity, see Anne Applebaum’s terrific Atlantic article, “The Collaborators.”) In the same way, favorable approval numbers in public opinion polls, or the pressure or a crisis, can give leaders more leeway to enact an antidemocratic agenda without risking reprisal.

Guardrails aren’t eliminated overnight: Norms are chipped away slowly, and any one change in isolation may be relatively innocuous. Taken together, however, piecemeal incursions against the practice of democracy can do significant, perhaps even irreparable, damage. In Four Threats: The Recurring Crises of American Democracy, published this past summer, Suzanne Mettler and Robert C. Lieberman delve into American history to understand the confluence of today’s threats. The authors note that forward progress by democratic regimes is not inevitable: Such regimes can also regress, and “it is a grave mistake to assume either that the United States is automatically democratic because of what our Constitution says or that we have moved steadily and inexorably toward greater democracy.” For Mettler and Lieberman, American democracy rests on four pillars—free and fair elections, the rule of law, recognition of the legitimacy of the opposition, and the protection of rights—that have been eroded at various times in the nation’s history. The threats include polarization, conflict over membership (i.e., citizenship), economic inequality, and executive aggrandizement.

The authors explain how each of these threats destabilized the country at various moments in history, including the founding, the mid-19th century, the period after the Civil War, the interwar period, and the Nixon administration. What is distinct about today is the confluence of all four threats at once. “It may be tempting to think that we have weathered severe threats before” and, therefore, will do it again, they write, “but that would be a misreading of history.” The survival of our democracy “is by no means guaranteed.”

How Democracies Die and Four Threats first dispel the notion that American democracy has been stable and progressive. There have been epochs of democratization resulting in voting-rights expansion and greater rights protections, but there have also been deep crises that have threatened the republic. In the United States, resolving these crises often involved highly suboptimal compromises—the perpetuation of racial hierarchy, for example. And in other countries, such crises led from backsliding to authoritarianism.

Both these books are digestible, and, aside from the bleak subject matter, even fun to read. Their analytical clarity makes them somewhat less depressing: They help us disaggregate political problems and think about where the bright lines are. According to these analyses, we have not yet become something that isn’t democracy. And having read them, we are better equipped to call out that which degrades democracy.

Sheri Berman’s Democracy and Dictatorship in Europe, published early last year, is a sweeping, magisterial history of political development on the continent that produced exemplars of modern democracy as well as some of history’s worst regimes. The book, which Berman dedicates to those “who have struggled to get rid of the ancien régime,” span four centuries and at least six different countries and regions. Berman looks at the complex dynamics of regime change and the political, social, and economic upheavals involved in building states, expanding rights, and fighting wars. While How Democracies Die and Four Threats are veritable beach reads for politics buffs (that’s a compliment), Democracy and Dictatorship in Europe requires donning glasses and the proverbial thinking cap. (That said, I actually did read it on the beach myself.)

In taking the long view, Berman shows us that the idea of a gradual and nonviolent path to democracy is a myth. Instead, “the political backstory of most democracies is one of struggle, conflict, and backsliding.” By examining long-run processes like economic development and nation-building, and by integrating these into her analysis of democratization, she shows us that the post-1945 liberal international order that resulted in strong, peaceful, democratic states in Europe was the historical exception rather than the rule.

Together, these books challenge the assumption that democracy is assured simply because it is extant or longstanding. The political conflicts that produced democracy involved struggles for power, control over institutions, and demands for recognition and dignity. But the powerful, even when they cede power, do so in ways that benefit themselves. As a result, democracy is always a precarious compromise.

The United States today faces its own reckoning. Why do we idolize the Founders—or Confederate generals? Why do many of our leaders refuse to acknowledge racial hierarchies that have persisted long after the end of slavery ended and deprive black Americans of full participation in political and economic life? Why does it seem impossible to change our anti-majoritarian institutions while the rest of the free world’s democracies have reformed their arrangements to reflect a diversity of viewpoints? If you’re interested in learning more about why our democracy seems impoverished or inadequate, these three books are a useful start.

Is American democracy backsliding? We’ll have a more definitive answer in November. While American elections have been held during wartime and other periods of crisis, never before have they been held under a leader who has openly threatened the very process of democracy by refusing to commit to accepting the election results or to a peaceful transfer of power should he lose. These last few weeks before the election are a good chance to read up on democratic backsliding, knowing that we are in one of those periods that requires vigilance.

Didi Kuo, an American Purpose contributing editor, is the associate director for research and a senior research scholar at the Center on Democracy, Development and the Rule of Law at Stanford University. Twitter: @didikuo1.