Destruction and Hope in Portland

How calls for justice morphed into the violence that struck the city.

By Nancy Rommelmann

Just before 1 a.m. on May 30, 2020, Noha Kassab received a text from her sister.

“Noha, there’s a lot of stuff going on downtown, you better watch the store,” Kassab recalled the message reading. From her home in Beaverton, Oregon, eight miles west of downtown Portland, Kassab contacted her four children. There might, she told them, be trouble at Kassab Jewelers on Southwest Broadway, the flagship store of the business she’d started with her husband in 1990.

Three of her children work in the family business. “They all have [security] camera access to the store,” Kassab said. “And we started watching.”

Kassab saw a group of young people enter the store. A boy in a ski mask swiped a laptop. A girl in cutoffs bounced a piece of furniture off a jewelry case. This group was replaced by a second group, then a third. A masked young man swung what looked like a homemade weapon into the display cases, shattering the glass and setting off a frenzy of hands grabbing.

“I feel like my store was raped over and over for an hour and ten minutes,” Kassab said. In the video, she could intermittently see the police directly outside her front door. “The police are standing on the corner of Alder and Broadway, doing nothing,” she said.

Kassab boarded up the store that day. It has yet to reopen. And if 14 months later she has not gotten over “the anger and sadness,” she has found a way to channel it: Last October, her attorneys filed a tort claim notice against the City of Portland, seeking $2.5 million in damages (including the theft of $1.5 million in jewelry), alleging that elected officials and the Portland Police Bureau “failed to plan or prepare for, and failed to adequately protect, downtown businesses.”

“They have a legal obligation to protect my property when there’s civil unrest,” Kassab told me in late June, sipping an iced latte at Washington Square, a suburban mall that houses another location of her business. “Why is it right now Portland is still, more than a year later, boarded up and closed? Because of our city officials, who lack leadership and they should all be fired. Fired, totally fired.”

“Seeing Portland like this breaks my heart”

Kassab is not wrong in her claim that “lack of leadership” contributed to Portland’s unmatched stretch of violent protests in the wake of the killing of George Floyd on May 25, 2020. But the medium that allowed the violence to bloom over 100 consecutive nights, with flare-ups to this day, is more multifarious and reckless—a giving over of common sense for what some saw as the common good. The belief that Portland was fighting the right fights—against Trump, against the police, for Black Lives Matter—had a tiny minority of citizens engaging in criminality, a larger portion willing to see past these crimes, and the majority staying silent, whether out of fear of being branded right-wing or racist or, given the pandemic, wanting to stay clear of the whole thing.

Kassab falls into none of these categories. She’s been critical of what’s going on in the city and intends to stay that way. A Palestinian raised in Kuwait, she came at age 17 to study at Oregon State University, where she was introduced to her future husband, a Lebanese immigrant. By the time she was 24, the couple had two children and were running a jewelry business in downtown Portland’s pawnshop district.

“Then we opened a store in Beaverton and expanded to Broadway, so that was a lot of work, hard work,” Kassab said, over her latte. “And then people go and write on my store ‘FYL’? You know what that stands for?” Kassab whispered, “Fuck your life.”

Kassab started to cry; her husband had suffered a heart attack at age 59 and died 18 months before the store was looted.

“The reason it hurts me is because he’s gone right now, and I look at the store he was so proud of, destroyed, and the city does nothing, nothing,” she said. “And I love Portland, don’t get me wrong. I grew up here. We used to brag about how safe Portland was ... you could walk downtown Portland in the middle of the night, and no one would get close to you. This is not the case anymore. Seeing Portland like this breaks my heart.”

Damage in pursuit of justice

“It’s so hard to figure out why I live here now,” Kurt Martig told me last August. I was interviewing Martig, a landscape architect, about the unrest in the city. He and his wife kept a TAB trailer and a Prius in the driveway of their small single-family home, typical of the homes in Portland’s Kenton neighborhood. Martig cut plums from a tree in his backyard and told me he’d moved to Portland from Ohio in 2016, lured by, among other things, people he assumed would share his liberal and libertarian values. What he found in the summer of 2020 were locals who considered the nightly violence acceptable—including when a few dozen activists, on the run from police after setting fire to the nearby police union hall, trashed the four-day-old outdoor shopping plaza paid for by Kenton’s small business owners. Then they did it again the next night.

“I go on Nextdoor.com and I’m seeing things like, ‘People have insurance, things are less important than lives,’” Martig said. “I’m like, guys, you’re hurting innocent bystanders, the business owners are getting hurt, the employees are going to get hurt, the customers, it’s all the way down.”

Others disagreed. Someone at the dog park told Martig he should factor in “the decades and centuries of oppression and understand why people are doing what they’re doing.” A friend told him that the cops were always worse.

“It kind of breaks down to, you can either be one way or the other,” Martig said. “Which is a false choice.”

Then there were those who seemed not alarmed by events, but inspired. “We saw them from our upstairs front window marching … back to Kenton Park. They were drumming and chanting. They sounded joyful,” a woman posted on Nextdoor the week of the plaza incident. “I have to say they brought tears to my eyes. I was proud of them. Keep up the nonviolent protests, young folks!”

At first, I could not understand the unwillingness to differentiate peaceful activists from those in it for the anarchy. Were people afraid the entire protest movement would be tarred if the destruction was acknowledged to be lazy and not getting anyone anywhere? But then I realized, it was getting people somewhere: It was landing the tiny minority, and by extension the city, in the spotlight. And if the star turn came at the expense of others—some of whom were black small-business owners, as many were in Kenton, or a Palestinian widow like Kassab—if you squinted hard enough, you could see damage in pursuit of justice as justifiable.

Driving out the rot

Where Kassab and others saw heartbreak and a collapse of civic responsibility, others saw Portland pushing toward an idealized version of itself: a place of progressive policies with the moral fortitude to pursue racial justice and to tear down institutions that exclude or persecute.

In terms of oppressing its black citizenry, Portland has a bad history. In 1844, the Provisional Government of Oregon voted to exclude black settlers from its borders. Redlining continued through the 1970s, and the city has seen its share of horrific racially motivated killings, including the 1988 murder of Mulugeta Seraw, an Ethiopian student beaten to death by three skinheads who claimed affiliation with the group White Aryan Resistance. In the supercharged days after Floyd was killed, these would be among the issues cited as evidence of the rot upon which Portland was founded. People questioned how anything new and honest could be built before the rot was driven out.

One factor, though: How amped-up were those doing the driving?

After Trump clinched the Republican nomination, many in Portland, where I lived from 2004 until 2019, fell into a kind of anti-GOP fever, one that did not break via “Not My President!” marches, impeachment fantasies, or the 2016 election of Ted Wheeler, a progressive politician, as mayor of Portland.

That Wheeler would oppose Trump was a given. What was not was how easily Trump’s rhetoric (“very fine people, on both sides”) and policies (“kids in cages”) would provoke Wheeler to steer Portland harder left, to make laws that offered the sensation of benevolence with none of the benefits. For instance, in February 2019, Wheeler presided over a city council meeting where the council unanimously passed a resolution to condemn hate groups. The officials didn’t bother to define what a hate group was, consider how this action would affect First Amendment rights, or discuss what might happen when others were in power—people who might consider them and their ideas hateful. As to that last, Wheeler was about to find out.

“There’s nothing we can do”

As soon as she saw the tape of her store being broken into, Kassab called 911. “The first time, I’m screaming—and I have all this documented—‘They’re breaking into my store!’ And [the dispatcher] goes, ‘I know, I know, there’s nothing we can do. We don’t have enough people.’”

If that’s the case, Kassab told the dispatcher, she was going downtown herself. “And he goes, ‘Nope, you can’t go downtown, it’s very unsafe.’ I said, ‘I can’t go downtown and you’re not doing anything?’ And he goes, ‘Yes. You can’t go downtown.’”

After Kassab again called 911 and was again told to stay away, her three sons and son-in-law headed to the store. When they got there, it was too late.

“People were still coming in, and my sons were yelling at them to leave, but this is all after the fact,” she said. As she would later write to friends and customers, the security tape showed, “9 Portland Police SUV’s, one Police Cruiser, 3 fully stacked riot police vans, 5 motorcycle cops, 3 fire trucks with lights on, all drive by at different times through the night and don’t stop to help us once.”

“They were told not to do anything,” Kassab said, of the police not stepping in. She does not know this from the police, only from what people told her.

When I asked whether there was an official policy that night, the Portland Police Bureau told me, “When we have large-scale events, it triggers an Incident Management Team ... The responses can change depending on a wide variety of circumstances, and rarely will we see any kind of blanket policy on responses. If we have resources available, we would typically respond to property crimes. But if we have limited resources, the [Crowd Management Incident Commander] would make decisions about priorities, such as life safety.”

Out of the more than 100 people seen on tape looting her store, Kassab says she knows of only one who was arrested and prosecuted. While the city’s new district attorney, Mike Schmidt, did commit to prosecuting deliberate property damage and theft, he also announced last August that his office would “presumptively decline to pursue criminal charges which result solely from the participation in a protest or mass demonstration.” The result was unsurprising: Masked people running around in the dark tended not to be arrested, and for those that were, the charges did not stick.

In November of 2020, 91% of all Portland protest arrests were not prosecuted. More recent data showed that, of 1,108 criminal cases referred to the DA’s office between May 29, 2020, to June 11, 2021, 64% were rejected “in the interest of justice.” When I asked for clarification as to what “in the interest of justice” meant, and for whom, I did not hear back.

Fiddling while Portland burned

Hours before Noha Kassab’s store was vandalized, thousands marched from Portland’s east side to the west, across the Burnside Bridge and into downtown. This was the city’s first large-scale protest to honor George Floyd and register anger at the police. Just after 10 p.m., a group broke off from the march and headed for the police station and courthouse known as Justice Center. They can be seen on video smashing in first-floor windows, setting fires, and destroying office equipment, unaware or not caring that there were prisoners and personnel one floor below.

The siege against Justice Center continued for weeks, with protesters ripping down the protective fencing the city erected, sandbagging doors, setting outside dumpsters on fire, and shooting fireworks inside. For young people who’d been sequestered for months, such direct action offered the impression that they were the new freedom fighters. And if some would soon start acting more Weather Underground than Southern Christian Leadership Conference, this, they could tell themselves, was what was called for now. Portland was not going to be another Charlottesville; the next police killing of a black man would not happen here. As the white college kid in the black bloc outfit told me, “We’ve tried for 20 years to do it another way. It hasn’t worked. Nothing changes except with violence.”

And yet the violence continued and nothing changed. It was the same scene every night—windows broken, fires started, the occasional bucket of feces thrown—the only innovation being when the violence spilled over to the Mark O. Hatfield Federal Courthouse next door. If locals saw this as OK or looked the other way, if people across the country were transfixed by Portland’s Anarchist Entertainment Hour, the Trump administration was neither. In June 2020, Trump signed an executive order dispatching federal troops to Portland to protect federal property.

Things had been hot in Portland before, but the addition of the troops created an absolute conflagration. For all of July and August, thousands gathered in front of the federal courthouse, where they sloganeered and screamed and bashed in the building’s boarded-over windows; locked arms in solidarity and were tear-gassed and in several cases wounded by federal troops. Reporting among this crowd, I can attest to how energized they were to be openly opposing what they saw as the police state and to have the eyes of the world on them as they streamed their revolution via cellphone. It seemed to intoxicate them and give meaning to what had been a very difficult year.

Wheeler, too, seemed to find meaning. Of all the progressive mayors in the country, he would be the one to go up against Trump for sending troops, would stand among his people and be teargassed, would consider what activists were urging him to do—have police fully stand down during demonstrations in hopes of sustaining a “calming de-escalating effect”—only to double back. He could not seem to pick a lane and was ever-reactive, both to Trump’s provocations and to the activists’ demands—fiddling while Portland burned.

The protests rolled into month four. Activists marched through residential neighborhoods, shining lights in people’s windows and shouting, “WAKE UP WAKE UP WAKE UP MOTHERFUCKER WAKE UP!” When I asked one of the activists what the goal was, she responded that because some people lived uncomfortable lives, these people should be uncomfortable, too. She and her crew seemed carried away at stirring up a little chaos, and I thought, for the 900th time, that they were lucky to be doing so in pacifistic Portland, that they would not have gotten away with it for long in Caracas or Detroit.

We can consider people entranced by chaos and think, “They’re young; they don’t yet have responsibilities and believe they are fighting for a better world.” This belief need not be sustained on building anything, only the collective effervescence that comes with tearing things down; as one activist who participated in the burning of the police union hall in Kenton told me, “I’m not going to lie: It’s fun.”

But fun for how long, when you’re engaging in the same sorts of destruction night after night after night? When you get up in the morning and there is no longer anything novel or newsworthy about broken glass and embers? Where does the emotional sustenance come from then? I sometimes saw the activists, 14 months in, as caught in a sort of bulimic loop, binging every night on figurative junk food only to get up in the morning feeling gross and undernourished and needing somebody to blame for the emptiness.

As the months wore on, the person they would blame was Ted Wheeler, who would endure a massive crowd chanting, “FUCK ted WHEEL-er!,” see his photo plastered around town with the words “WANTED! DEAD OR ALIVE,” be repeatedly attacked while at restaurants—and finally, after activists camped out in front of his condominium and demanded he move out, move out.

“There are some people who just want to watch the world burn”

The second week of September, more than 700,000 acres around Portland burned. The air was full of particles and an eerie yellow, and citizens were ordered to stay inside. This is the reason the uninterrupted nights of violence capped out at 100. They started up again the following week. On September 23, at least one Molotov cocktail was thrown at officers. On October 11, in opposition to Columbus Day, activists tore down statues of Theodore Roosevelt and Abraham Lincoln.

As the presidential election neared, several people suggested to me that, were Biden to win, things in Portland would calm down. I told them that not having the serial provocateur Donald Trump in office might take the edge off, but that the activists did not consider Biden their man; that their guiding star, so far as I could tell, was the destruction of those they perceived as enemies.

I saw this when they scrawled anti-Semitic obscenities on an Israeli restaurant that was part-owned by a Palestinian. I saw this when they stole my phone and called me “a fash.” I saw this clearly in the video of activists celebrating the shooting to death of Aaron Danielson, a member of the Trump-supporting group Patriot Prayer, by a self-proclaimed BLM/antifa supporter.

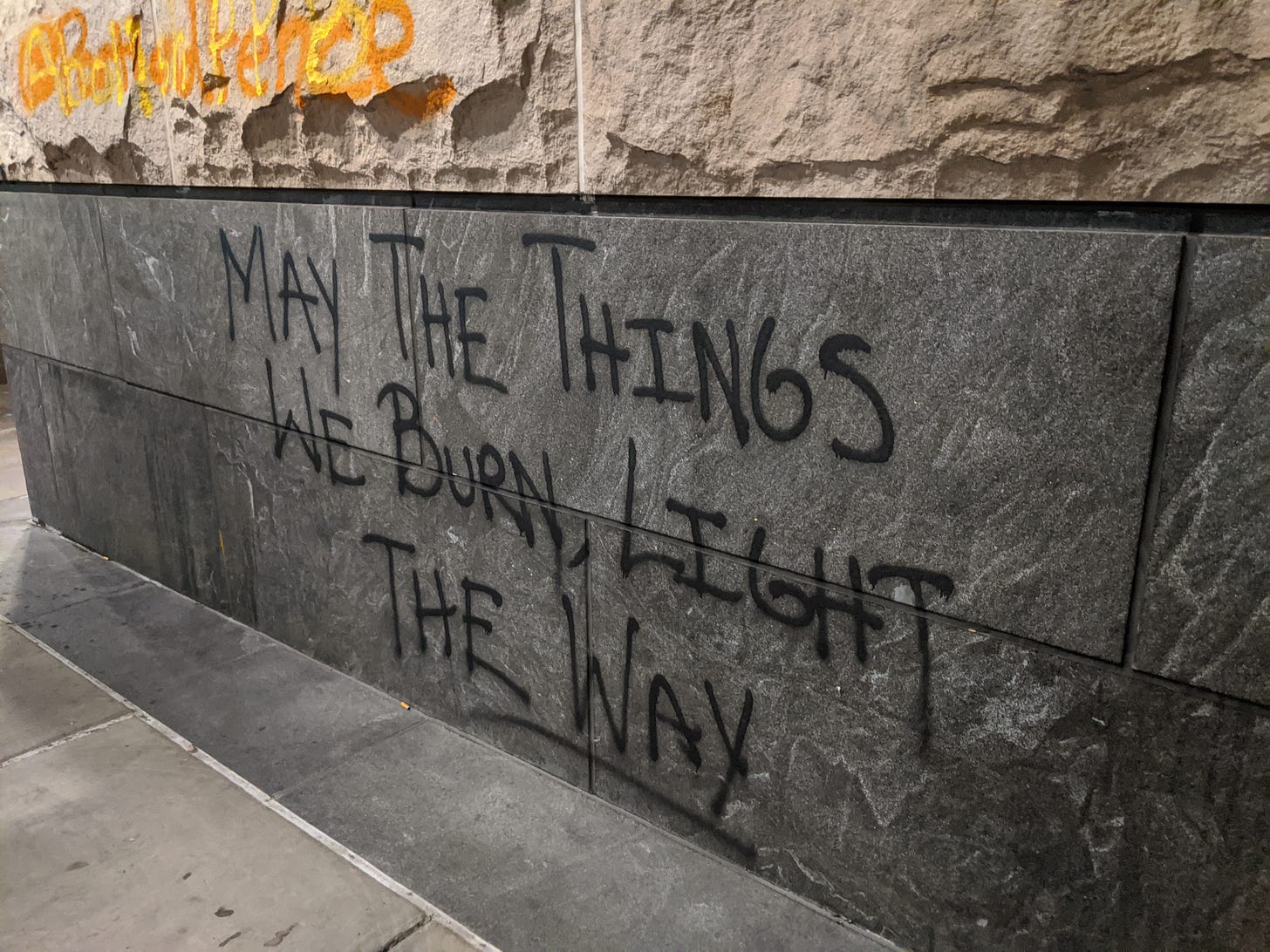

The day after Biden was elected, about 150 activists gathered in a city park, passed out flyers (“Are You An Anarchist? [the answer might surprise you!]”) and marched up Southwest Broadway, past Kassab Jewelers and past Nordstrom, whose windows were also boarded over and onto which someone spray-painted “FUCK TED.” Among the crowd were two guys carrying rifles; one of them told me, in a conciliatory tone, “We’ve started carrying in Portland and, overall, we’ve gotten a great reception.”

This great reception was not extended from organizers of an event, sponsored by local BLM groups, that was taking place along Portland’s waterfront. That event’s emcee challenged the 150 activists squatting on a curb across the street, urging them to join the peaceful protest, to “stop standing separately and get the fuck over here.” The activists did not get over there and instead continued their destructive march through the city, bringing down store windows in cascades of glass and spray-painting the 108-year-old Benson Hotel. The hotel’s managing director, George Schweitzer, scrubbed off the paint, the umpteenth time he had done so, at a time when hotel revenue in Portland was down 81% from the year before, with no relief in sight.

Before the year was out, activists would repeatedly swarm the home of a newly elected city commissioner (because he’d voted against the latest proposed cut to the police budget), establish an autonomous zone (where some occupiers carried semi-automatic weapons), and, on New Year’s Eve, break more windows and set more fires, despite the fact that, as a local news station reported, it was “unclear what the main thrust of the gathering is.”

Wheeler acknowledged the emptiness of the New Year’s Eve protest, if not how his equivocating had helped paint the city into this particular corner. “It’s hard for most of us to even comprehend what goes on in the heads of people who think it’s OK or a good idea to go on a violent rampage through the city on New Year’s Eve and during a pandemic,” he said. “It’s the height of selfishness … There are some people who just want to watch the world burn.”

Turning back, staying home

The song “Portland” by The Replacements includes the line, “It’s too late to turn back, here we go.” But as the pandemic receded, as schools and bars and restaurants reopened, the activists did turn back.

Attendance at the nightly direct actions dwindled throughout Portland’s notoriously inclement winter weather and did not resume come spring. The entire Rapid Response Team, the Portland police unit that deals with crowd control, resigned in June in response to one of its officers being indicted for pushing a protester a year before. Some in the police, including an officer I spoke with, feared that activists and the Proud Boys would take advantage of the void and stage a battle royale. Instead, on June 18, a handful from each group showed up at a suburban park, chased each other around with bear spray, and went home.

The world was moving on, and so was its fixation on Portland. Maybe activists wilted without the sunshine of the media. Maybe they wanted new identities. Maybe the nightly marches got boring. At least one couple I know who’d participated for months said they started staying home at night instead to play Catan.

They and other activists could choose to stop fighting, to take off the black bloc. And while it was possible that a few hardcore radicals would head underground with a copy of The Anarchist Cookbook, the majority likely just wanted to enjoy, unmasked, another Portland summer.

Optimism and disturbing the narrative

“Things here in Kenton have been really quiet. I can't remember when the last protest was,” Kurt Martig told me in late June. A year earlier, he had not seen reasons to stay; now he, his wife, and their new baby had moved into a new house in Portland, taking advantage of the city’s go-go real estate market to sell their old home at way above the asking price.

“The vandalism has slowed down,” Schweitzer, at the Benson Hotel, said. “We waited to go through the anniversary of George Floyd’s death, and then all the hotels downtown basically removed the boards from the windows.”

Schweitzer credited officials for stepping up arrests.“The numbers I heard are, up to 60 people have actually been charged with felonies, and that a high number of those will probably stick.” The district attorney “is working to make sure that people who were vandalizing,” the ones “really out for different reasons than Black Lives Matter,” are brought to justice, he said.

I asked the DA’s office in June for updated data and was told, “In January, law enforcement started marking ‘targeted arrests’ of those engaged in the crimes related to civil unrest that involve arson/burning, property crimes, person crimes, or weapon crimes, and improved their investigative response to these priority cases. Those types of crimes are the cases District Attorney Mike Schmidt has always said he wants to prioritize.”

After I left Schweitzer, I walked up Southwest Broadway. Downtown looked brighter, from last summer certainly, but also last winter, when the place felt abandoned and ghostly. People now clogged the streets, and while some stores were boarded over, most were not.

Things seemed changed, and hopeful. I tweeted as much in a video.

The vehement pushback to my optimism was, depending on how cynical you are, predictable or astonishing. People did not want to hear good news if it conflicted with their preferred narrative that Portland was an anarchist shithole. Like the activists, they had chosen their enemies and were not interested in disturbing that picture with the reality on the ground now.

Well, too bad. Things are improving in Portland, and anyone who wants this not to be the case might ask themselves why.

Moving on

On July 19, 2021, Cyan Waters Bass was sentenced to four years in prison for arson and assault during a riot last September. The DA’s office said Bass pleaded guilty to using “a wrist rocket slingshot to damage multiple windows in the Justice Center and then used a flammable liquid to set the building on fire … Bass then ignited a Molotov cocktail and threw it in the direction of police officers.” Bass was 21 at the time; in his mugshot, he looks not displeased. Perhaps he was proud to suffer for his cause. Or perhaps he thought there would be no consequences. At the time, it was easy to slip away without prosecution, to fight another day.

Those days appear to be gone. While it remains to be seen whether the crackdown on criminality will last, it is hard to imagine Portland officials tolerating a resurgence of activist violence.

Still, if some businesses along Southwest Broadway see Portland returning to what it was, Kassab Jewelers does not. “Every time I get close to opening that store, something happens,” Noha Kassab said, of the still boarded-over location. “Whether it’s happy stuff—the George Floyd police got convicted—they still went downtown and broke glass. That’s a vicious cycle. I understand why people are angry, but how does that make it right when you destroy other people’s businesses?”

As Kassab’s case against the city moves forward, her fury with officials remains fresh. She is not the only one. Last month, a group started collecting signatures for a recall campaign against Wheeler.

“I would be the first one to go for that,” Kassab said. “And there should be a recall against Mike Schmidt as well ... I truly believe it’s our local officials that have destroyed Portland. It’s the decisions, the lack of accountability … Since when do you go and break someone’s glass and not be held accountable? … Where is my right as a taxpayer, as someone who’s built a business? Why do these people have more rights?”

Because politicians handed them over. We all did when we were happy to have Portland center-stage, hungry to see how valiant or asinine its players could be. But we should not forget, and it took me a long time to remember, that these are very young people, living through a pandemic that knocked many twice and three times their age on their asses; that no doubt took some of their jobs and killed some of their loved ones. People barely out of their teens have very few tools. They make mistakes. Like the rest of us, they don’t want to be lonely and so they go look for a tribe. For these reasons, I can see why a tiny minority of citizens created such a big mess and then, after the ardor cooled, moved on.

What is harder to square is the inaction of the grown-ups—the people in positions of power who pledged to protect their electorate, then gave so much purchase to raw partisanship and were willing to let citizens pay the price. If Kassab is angry about this, she has a right to be, when what she is asking for is the minimum obligation she might expect. “Safety,” she said. “I just want my business open and to feel safe.”

Nancy Rommelmann is a journalist and co-founder of Paloma Media.

This article reflects the views of the author and the individuals quoted herein, not necessarily those of Persuasion.

An earlier version of this article referred incorrectly to the date that Noha Kassab and her husband started their business. They started it in 1990, not 1983.

The DA and mayor decided political violence was ok, as long as they agreed with the cause. It really isn't much different than a 50s sheriff in the South looking the other way at Klan violence.

The biggest question to me now is why wasn't the FBI more active in bringing federal racketeering charges against Rose City Antifa and others engaged in conspiracy to commit violent crimes. Many former FBI officials have been speaking out to express their shock at this dereliction.

A solid demonstration of how to think and write perfectly reasonably about a perfectly unreasonable situation. I have mixed feelings about the piece--some very positive and some very negative--and will have to think a bit in order to sort it out. The line that disturbs me the most is the bit about "...the majority staying silent, whether out of fear of being branded right-wing or racist or, given the pandemic, wanting to stay clear of the whole thing." If it was only a story about property damage that would be one thing, but there were abundant and perfectly serious death threats underscored by multiple physical mob attacks. And the explicit stated goal of Antifa and many other organised rioters is to "tear the system down" presumably with property damage being an important symbolic element. Hopefully the majority will come out of it's stupor sometime soon. Towards this I would like to see more investagative reporting on this story and would welcome stories that are not afraid disturb and to expose enemies of the public and the leaders of organised violence against our institutions. The reflexive cancellation of a young British musician over the mere mention of Andy Ngo's book does not point in a good direction and I am concerned that the silent majority will not get the raw information and facts needed for them to sort out how much we should value "the system" and whether it is worth defending or not.