After a time-out of nearly ten years, I finally decided to return to building and flying drones. I had done this quite intensively after I first moved to California in 2010, getting help from Chris Anderson and his 3D Robotics colleagues, and wrote about how cheap drones would affect global politics in the FT. I gave this up, however, after I had an A-fib attack flying a drone near my house, ending me up in the hospital. I found drone flying to be extremely stressful; it is easy to crash or lose an expensive drone, and they can do a lot of damage if they hit someone. That’s why I started building terrestrial rovers instead, which can’t get out of hand the way a drone can.

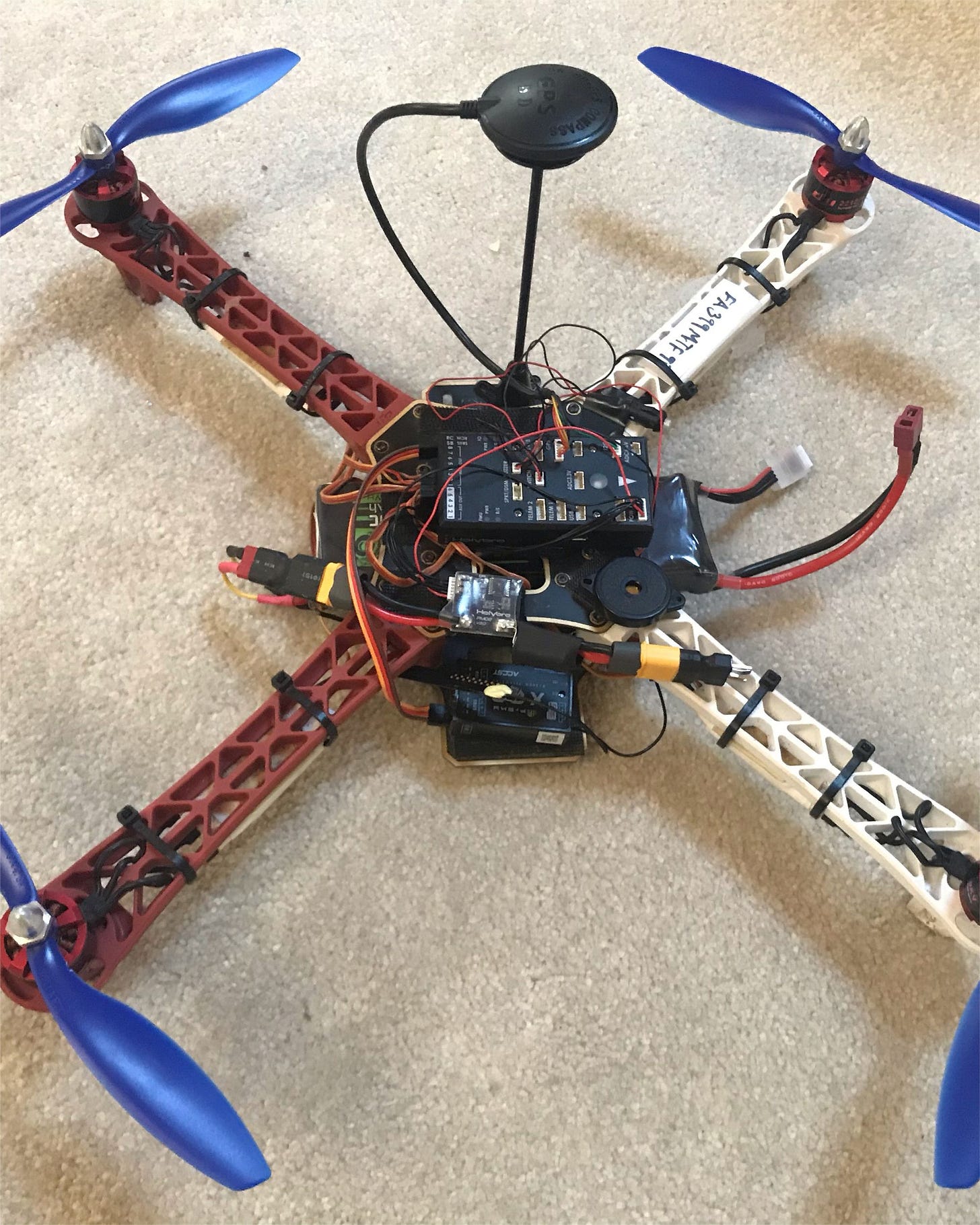

The technology in the meantime moved on very substantially, both for amateurs like me and in the world of geopolitics. Over the past couple of months I replaced the Naza flight controller in an old DJI drone with a Pixhawk 4, which is a descendant of the open-source 3D Robotics software and hardware. Ardupilot’s Mission Planner software allows you to program a drone to fly to series of waypoints on the map and return to where it started, without having to actually fly the machine manually. The first-person view cameras have gotten very small and very high-resolution, allowing you to fly through doorways and under underpasses while recording everything in 4K video.

___STEADY_PAYWALL___

The Ardupilot hardware and software is a real pain in the ass to install. The flight controller comes in a wide variety of models (all sourced from China, and these days requiring several weeks to deliver), and needs to be mated with a GPS, transmitter and receiver, compass, telemetry radio, barometer, and a wide variety of sensors. This is not a plug-and-play operation; you need to go through countless pinout diagrams and YouTube videos to figure out how all this stuff interoperates. The Ardupilot software allows you to set hundreds of parameters, making it very flexible but also very complex and hard to work with. Nonetheless, it has become the control system for a wide variety of professional drones, rovers, and boats.

Ten years ago it struck me that inexpensive consumer drones could easily be repurposed for targeted assassinations and used by a wide variety of countries or terrorist groups. An Ardupilot-equipped drone could be programmed to fly to a point on the map and then drop a grenade on someone; you could not jam it because it is dependent only on passively receiving a GPS signal. The FT published a piece recently about how the al-Tanf base in Syria with 200 U.S. personnel had been attacked by Iranian-linked drones, and how Iraqi Prime Minister Mustafa al-Kadhimi was the target of a drone attack last November. Even the Taliban, which has been relentlessly targeted by U.S. drones, has been able to field its own drones and use them to attack enemies within Afghanistan. Drone technology, in other words, has been democratized, and is no longer the exclusive preserve of advanced countries like the United States and Israel. There are a wide variety of defense contractors working feverishly today on methods for defeating such low-cost drone attacks, but no technology has yet emerged that will effectively do the job.

If we move up to a higher level beyond large consumer drones, we see that these machines have the potential to change the nature of warfare rapidly. Last April I wrote about the impact of Turkish drones on the conflicts in Syria, Libya, and Nagorno-Karabakh. (This turned out to be the most widely shared piece American Purpose has published.) Since then, the Ethiopian government under Abiy Ahmed has used military drones to turn back the Tigrayan offensive that was threatening the country’s capital, Addis Ababa. Turkey is also supplying Ukraine with drones, one of which was used to target a Russian artillery emplacement in Donbas, which provoked a furious Russian response. Ukraine has received not just drones but drone manufacturing capability from Turkey, and Ukrainian engines are being incorporated into their designs. These drones could significantly raise the cost of a Russian invasion.

It seems to me that military drones have the potential to profoundly change the nature of land warfare. Drones are not good as offensive weapons, because they by themselves cannot be used to seize and hold territory. But they are excellent as defensive weapons, and can defeat the heavy combined arms forces that most modern militaries, like those of the United States and Russia, currently employ. The relative balance between offense and defense has had a huge impact on military outcomes and therefore geopolitics over the centuries, and we may be at the beginning of a new shift in the balance. This will be the topic of my next post.