Fascinating Rhythm

The story of race in America isn’t a straight line but an improvisation, featuring not just harmonies but collisions that create outcomes no one can anticipate.

On one emotionally unsettled evening about a year ago, just a few days after the upheavals of May 25, 2020 began to blossom in Minneapolis and across the United States, I found myself 9,650 miles away in Singapore taking solace in the music of Fats Waller. I’ve been a fan since my early twenties, partly because listening to his music invariably cheers me up. But on that evening I chose “(What Did I Do to Be So) Black and Blue.” It’s not a favorite compared to “Ain’t Misbehavin’,” “Honeysuckle Rose,” and many others, but on that sultry Southeast Asian evening, it appealed as a way to connect myself to what was happening back home.

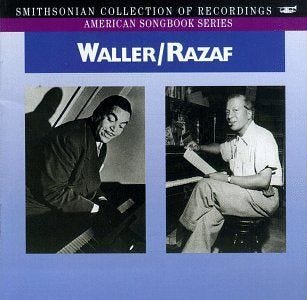

What all those songs have in common, aside from having been recorded by Fats, is that the lyrics were written by Andy Razaf, who also wrote the lyrics for “Stompin’ at the Savoy,” “In the Mood,” “The Joint is Jumpin’,” “That’s What I Like ’Bout the South,” “Elevator Papa, Switchboard Mama,” and nearly eight hundred other songs in a multi-decade career.

I’d seen Razaf’s name hundreds of times over the years on record labels and in liner notes, but for some reason, that night made me want to learn a bit more about him. My first shock of discovery came quickly: Andy Razaf’s birth name was Andriamanantena Paul Razafinkarefo. Born on December 16, 1895, in Washington, DC, his name seemed, well, atypical for an African American. He was the child of Henri Razafinkarefo and Jennie Waller (no relation to Fats). Henri was the nephew of Ranavalona III, the queen of Imerina, and Jennie Waller was the eldest child of the American Consul to Imerina, John Louis Waller.

You’ll be wanting to know at this point what, or perhaps where, the deuce is “Imerina.” It’s what we now call Madagascar. You’ll also be wanting to know why, if Henri and Jennie married and conceived their child on a large island east of the African continent, little Andriamanantena was born in Washington. It’s because Henri and Jennie suffered from bad timing: The French military was about to extirpate the Kingdom of Imerina, a going concern since 1540, and John Louis Waller, fearing for the safety of the newly wed couple and their unborn child, shipped off the expectant mother to America before the violence unfolded. It was a wise decision: Henri died resisting the French aggression. Neither father nor son ever saw one another. Nor did the young Razaf ever set foot on African soil.

Andy Razaf was raised by his mother in the company of her father, who joined grandson and daughter sometime around Andy’s second birthday. They lived together in the New York City area—and for a few years in Cuba!—along with Waller’s wife and her two children from a previous marriage for Razaf’s seminal first decade, until Waller died at age fifty-six in 1907.

Razaf’s biographer Barry Singer speculated that living with his grandfather had a significant impact on the development of his personality and temperament, and indeed the two were alike in many ways. Both were strikingly handsome. Waller was taller, darker-skinned, and broader-chested than the part-Hova Razaf, but old photos attest to the resemblance. Both were resistant to intimidation and failure, yet both suffered disappointments and setbacks aplenty; indeed, both tumbled in later life toward undeserved obscurity. Both were doggedly optimistic and deeply patriotic, even in the face of relentless bigotry. Both were gifted with keen intelligence and mastered the charms of oral and written language, and both were devoted to the advancement of literacy and education for their fellow African Americans

We are living amidst a moral panic over race, in which actors of varying motivations deploy ideologized slogans in an attempt to reduce everything to deterministic and conflictual group essences. These caricatures imagine a binary, White/Black world in which highly abstracted “colors” somehow become cultures. The starkest recent example of this is a poster created (and quickly withdrawn) by the Smithsonian Museum of African American History that asserted that qualities like hard work and rational thinking are manifestations of “Whiteness” and “White Culture.” Imposing such a framework on the richly complex lives of these two remarkable men—John Louis Waller and Andy Razaf—would make it impossible to do justice to their joint story. It would also rob us of a teaching moment, one that might restore clear recognition of both the true arc of American history and hope for its future.

These two stories—Waller’s in particular—are virtually unknown today.1 Before that fateful evening in steamy Singapore, I had never heard of John Louis Waller or the Kingdom of Imerina. An informal sampling of colleagues and friends revealed that I was not alone. A conjoined story of these two men would be a tale with many layers that could easily fill a book, or even make for a blockbuster adventure movie. It’s also a tale that needs to be told—and told now.

Talent Meets Opportunity

John Louis Waller was born a slave in January 1850 (or possibly 1851) in Madrid County, Missouri. Waller’s parents and eleven siblings were all the property of the Sherwood family. Slave owners typically broke up families, but the Wallers remained intact over many decades. Waller’s father, Anthony, was the Sherwoods’ carriage driver, his mother, Maria, ran the kitchen, and John’s older siblings were responsible for the animals, the well-house, blacksmithing, carpentry, and other household tasks involving tools and the skillsets associated with them. None worked in the fields.

Young John Waller got the chance to travel with his father and the Sherwoods, opening up vistas denied to most slaves. In November 1862, when he was eleven or twelve, the Sherwoods’ slaves fled their masters, as did most slaves in that part of the country when the opportunity arose. A Union Army brigade took them and others in and brought them to Tama County, Iowa, near Cedar Rapids. Anthony tried to farm on land provided to him, but it was tough to make ends meet for his large family, so he hired out John to the nearby Wilkinson family to work a variety of chores. Mrs. Wilkinson recognized John’s intelligence and taught him to read.

Literacy changed young John’s life forever. He read everything he could get his hands on, was able to go to non-segregated public schools, and earned his high school diploma in the town of Toledo, Iowa. He then apprenticed himself to be a barber, that being one of the few trades acceptable for African Americans to practice with White customers. He even started college but was called back to the Waller farm when sickness struck the family.

When things improved at home, John went to Cedar Rapids in 1874 to work as a barber; as one of the few literate African Americans there, he soon emerged as a rising community leader and began to write and speak about community issues. N.M. Hubbard, a local lawyer, recognized his talent and invited him to study law. Waller excelled and, at age twenty-seven, just as Reconstruction was ending, he was admitted to the Iowa bar. Had it not been for the peculiarities of his arrangements with the Sherwood family and the encouragements of Wilkinson and Hubbard—all ordinary, 19th-century White Midwestern folk—John Louis Waller would not have become the man he did.

At that time, too, Benjamin “Pat” Singleton was urging recently emancipated slaves to leave the South for Kansas, a new promised land far from old humiliations and enduring bigotry. As tens of thousands of “Exodusters” arrived in 1878–80, John Waller decided to join and, if possible, become a leader in a semi-autonomous and would-be self-sufficient African-American community. He set up shop in Leavenworth, but as a lawyer he attracted few clients: Most Whites were reluctant to hire him, and most African Americans couldn’t afford him. So Waller made ends meet by opening a barbershop.

Unfortunately, Kansas was poorly suited to be a promised land: The harder soil of its colder, drier climate would not support cotton, indigo, or most of the other crops the former slaves knew how to grow. In the end, some two-thirds of the Exodusters returned to their families in the South.

But Waller stayed in Kansas and in 1879 married Susan Boyd Bray, a widow with two children, Paul Henry and Minnie. Susan was deeply literate (she could also read music) and political (she was an outspoken suffragist). John and Susan had three children together: Jennie, John Jr., and Helen. After they married, John and Susan moved the family to Lawrence, Kansas, joined a socially upscale AME Church, and quickly became part of the town’s African-American elite. With others he and Susan helped form an African-American literary society, which offered help on the side to those wishing to learn to read.

John immersed himself in local politics as a loyal Republican and, in those days, as a declared prohibitionist (even though he was a silent partner in a local saloon to help pay the bills). Over the next several years, he worked as a lawyer when he could, owned barbershops, and in due course started a newspaper for Negro readers, for which he wrote eloquently and passionately on behalf of equal rights and equal opportunity according to the post-Civil War law of the land. He was a remarkably eloquent orator, and his youthful prominence prompted some older, more established African-American leaders to oppose his ambitions. He tried to climb the greasy pole without compromising his values, which included strenuous efforts to oppose creeping school segregation in Kansas.

At the time, the size of the African-American vote in some Midwestern states mattered to White politicians, as Republicans saw the Democrats gaining on them. Even in Kansas the bosses sought out African-American opinion leaders who could help keep them in office. Waller understood this and hoped for White patronage to help him break through politically at the state level. He thus consistently opposed union strikes and boycotts mounted by African Americans, hoping to persuade the Whites who could boost his prospects that he was a reliable team player. He seemed on the verge of success on a few occasions, but each time, another African-American politician undermined him or higher-echelon Republicans chose a White man for the post Waller sought. He got a series of minor patronage jobs, such as being a purchaser for the Kansas state prison system.

As he struggled to advance his political career, Waller continued reading, writing, and speaking. He kept himself abreast of the progress of the industrial revolution and became an enthusiastic pro-capitalist, believing that entrepreneurship offered a route for emancipated slaves to lift themselves out of poverty and dependency. He also developed an ear for the “return to Africa” activism of the day. He had read of the post-1833 British experiment in Sierra Leone to repatriate freed slaves to Africa, and he knew the mixed story of Liberia. In the 1880s, the Reverend Henry McNeal Turner of the AME church and the Liberian educator Edward Wilmot Blyden became the most influential of many back-to-Africa voices. Waller considered their arguments.

In 1888 Waller campaigned enthusiastically for Republican presidential nominee Benjamin Harrison. Republicans considered the African-American vote in several Midwestern states crucial to their chances of wresting power away from Grover Cleveland and the Democrats, who were busily using the 1883 Pendleton Act, which reformed the civil service, as a means to insert bigoted Southerners into the federal government (exactly as Senator George H. Pendleton intended), thus further ensconcing Jim Crow and rolling back civil liberties for African Americans in Northern towns and states. In a close election in which Harrison won the election but lost the popular vote, Kansas went solid Republican. John Waller was chosen to deliver Kansas’ electoral vote tally to the Electoral College in Washington, a ceremonial first for an African American born into slavery.

After the election, Waller’s admirers lobbied President-elect Harrison to make him U.S. ambassador to Haiti. That post, however, went to Frederick Douglass. Waller ended up with an appointment as steward of a state insane asylum, and then as manager of a state school for the blind.

Kansas Democrats tried to use Waller’s disgrace to attract African-American voters in what was shaping up to be a close race for governor. Waller refused to be used, however, and campaigned hard for the successful Republican candidate. With that, his big break came: At the urging of the new Republican governor, Lyman Humphrey, in February 1891 President Harrison appointed Waller U.S. consul to the Kingdom of Imerina. Waller arrived in the port city of Toamasina, site of all foreign consulates, on July 26.

Missteps Meet Misfortune

The reasons that Presidents appoint people to diplomatic posts don’t always align with the desires of high and mid-level State Department officials. Harrison’s main aim was at best general with regard to Madagascar: advance U.S. commercial interests, and don’t let the Europeans push Americans around. Concern for the prestige of rising American power was no small thing at the time. Besides, American commerce with Madagascar then exceeded that of both the French and the British.

The State Department further instructed Waller to establish cordial relations with the royal court and to resist French efforts to insinuate themselves further into the kingdom’s affairs. More specifically, Secretary of State James Blaine instructed Waller to present his credentials to the queen, not to the French resident-general.

This was a tricky business. The Berlin Conference of 1888, which divided sub-Saharan Africa among European imperial contenders, designated Madagascar for the French sphere, while Britain, at least informally and subject to the whims of outflowing historical contingency, received an uncontested sphere in East Africa. The Hova royal court had earlier granted an exclusive commercial contract to a Frenchman—an adventurer and slave trader named Joseph-François Lambert—and over time the royal house developed a taste for European styles and stuff, including making Christianity the island’s official religion not very long after an earlier ruler had banned it as part of a campaign to resist European encroachment. Alas, mid-19th-century Madagascar experienced horrific misrule and tumultuous times, all of which combined to open the door to renewed European predations later in the century.

In this way, the Hova elite risked the kingdom’s sovereignty for its own narrow version of modernization, but its pride obviated full symbolic capitulation. The Hovas also believed for too long that they could revoke European privileges at will. What the history books call the first Franco-Hova War (1883) put paid to that presumption. In 1890, two years after Berlin, the British recognized Madagascar as a French protectorate. At that point, the rising Americans—not party to the Berlin deal—stood out for the Hova court as the only potential counterweight against the encroaching French.

The Americans understood this, but so did the French. To navigate the Franco-Hova standoff, European governments had instructed their diplomats to present the exequatur, or credentials, before the French resident-general, even as they then rushed to the highland Hova capital of Antananarivo to say, “Sorry, just kidding!” Waller’s first journey up the hillside came just days after his arrival; as instructed, he presented his credentials to the queen at a lavish ceremony. He had not been to see the French resident-general.

No other foreign legation to the Hova court was led by a dark-skinned diplomat, and the French took Waller’s behavior, together with his skin hue, as the classic glove-slap to the face we read about unfailingly in old French novels. They totally lost their savoir faire at the Champs-Élysées and went batshit crazy (or skillfully pretended to—one never knows for sure). The French foreign minister, Alexandre Ribot, fired off diplomatically extravagant notes to Washington claiming a deliberately unfriendly act and suggesting that the French might forcibly expel Americans from the island and expropriate their property.

For some reason, this startled the guys at the State Department, who did three things in short order: considered pulling out of Madagascar; apologized to the French and cynically blamed the novice Waller for freelancing beyond his call of duty; and instructed Waller to make haste and amends to the French resident-general. Waller pleaded with the department to stand publicly by the instructions he had been given, lest his credibility be wrecked; all he got in return was silence.

Waller could have resigned in humiliation or capitulated meekly to his new instructions. He did neither. He reluctantly visited his French counterpart, but, having been backstabbed before in politics, he managed to persuade the State Department to drop any thoughts about leaving the island or distancing the United States from the Hova court. He appealed to the reputational damage such moves would cause, and did not restrict his advocacy to the State Department.

After the dust of his first week at work had settled, Waller set out to cultivate relations with the queen and her court, smiling over his shoulder at the French all the while. Waller may have been a novice diplomat, but he was as shrewd a tactician in a political contest as anyone. He did not allow the fact that his distant superiors had treated him as a piñata to daunt him.

But Waller’s arrival and shocking first act changed matters irrevocably. The more progress Waller made with Queen Ranavalona III, the queasier and testier the French got. The tipping point came back in the United States in November 1892: Grover Cleveland defeated Harrison to reclaim the White House for the Democrats. Waller knew his tenure would soon be over, so he redoubled his entreaties to the new secretary of state, Walter Gresham. He even broached the idea of a U.S.-Hova trade and security alliance. Alas, such a step would have been a casus belli for the French, and a war with the French Empire was about the last thing any U.S. President wanted to preside over, given the massive collateral trade damage it would cause. Waller got nowhere.

Worse, Gresham replaced Waller with Edward Telfair Whetter, an unreconstructed racist from Chatham County, Georgia, whose slaveholding family’s fortune had been ruined by the Civil War and Reconstruction. After Whetter arrived in Madagascar in January 1894, he manufactured a series of unfounded accusations about Waller’s malfeasance in office. Whetter later recanted some of his accusations when department higher-ups in Washington questioned his lack of willingness to provide evidence, since he had none to provide. But he did manage to drag Waller into court over his supposed mismanagement of the estate of a deceased American trader who had lived in Madagascar.

Both African Americans and White Americans had backstabbed Waller before, but none with the viciousness of a former slaveholder like Whetter. Yet despite all he had been through, Waller retained an almost childlike belief that right would triumph in the end, and that the spirit of optimism and entrepreneurship would be its vanguard. So as his tenure ended, Waller devoted himself to persuading the queen and her powerful husband/prime minister that the best way to thwart French encroachment was to attract massive American investment to the island.

Waller proved very persuasive: The queen soon granted Waller personally a roughly 225,000 square-mile concession in the teak- and mahogany-rich southern part of the island. Announced on March 19, 1894, “Wallerland” was to become “a colony for American Negroes.” Waller planned to divide the concession into plots, initially offered rent-free, in order to attract former American slaves to Madagascar. This was late-century American imperialism with a twist: Waller’s combined pro-capitalism, pro-“back-to-Africa,” pro-self-sufficiency dream would surpass Sierra Leone, Liberia, and Kansas as a promised land. Through Wallerland’s success, he could help the Hovas and also boost American prestige as the premier anti-colonialist force in all of Africa.

Waller understood full well the moral dilemma involved in what he was doing. Slavery was still legal in Madagascar. The Hova court and upper classes had for centuries owned slaves acquired in raids and local wars, and they had sold slaves, too—first to Arab and Persian traders come down from Oman and Zanzibar, and later from the northern town of Diego Suarez to Portuguese, French, and British slave traders. European observers at the time described the Hova—Austronesian people arrived from Borneo many centuries earlier by sea—as “dusky,” “tawny,” and straight-haired, in contrast to darker-skinned with tight-curled hair Bantu-speaking east Africans. Hova slaves tended to be the latter, tribes who had migrated in previous centuries to Madagascar from the eastern region of the continent.

So there was Waller, born a slave, making common cause with a slaveholding Austronesian master class.2 (Consider, while you’re at it, Andy Razaf’s inner reality: His maternal grandfather was born a slave; his paternal grandfather, a member of the Hova royal court, probably owned slaves.) But his dream of Wallerland, and all the redemptive good he believed it could do, urged him on.

To help seal his alliance with the queen, Waller soon gave his blessing to the union of his daughter, Jennie, with the queen’s nephew Henri. Waller waxed increasingly optimistic: For once in his life big things seemed to be headed in the right direction, and fast. He made quick progress in part by dispatching his stepson Paul Henry, who had been hired as an attaché at the consulate, to find tenants for Wallerland from the nearby island of Mauritius as a first step.

From Misfortune to Misery

Alas, the closer Waller got to the Hova and the harder he worked at making Wallerland a reality, the closer the French came to deciding to end the pretense of Hova independence. Whetter, meanwhile, got on well with the French—too well, in fact. Within weeks of the announcement of the Wallerland concession, the French decided to force Hova capitulation, knowing that the U.S. government would no longer object or resist.

French aggression began with the bombardment and occupation of the port of Toamasina (Tamatave to the French) in December 1894. Waller was there, having been forced to abort a trip home to raise funds for Wallerland, thanks to Whetter’s legal harassment, so he experienced the attack firsthand. A month later, the French shelled Mahajanga, on the island’s west coast.

Waller should have realized at that point that nothing much he could do would prevent the French from consolidating their control. Perhaps he did realize it. But his sense of honor drove him to what, in retrospect, looks like risky business. To this day, the evidence is mixed as to what really happened, but it seems that during or soon after the shelling of Toamasina, Waller tried to relay intelligence to the royal court as to what was happening—and perhaps indicated a willingness to secure weapons for his friends. Letters he wrote to his wife were later confiscated and used as evidence when the French arrested Waller and court-martialed him as a spy.

The only American response to the French attacks was Whetter’s ordering Waller detained on charges related to the trumped-up estate mismanagement accusation, likely in hopes that the French might arrest Waller later for other reasons. That is indeed what happened: Whetter informed the State Department that the French had arrested Waller in Toamasina on March 11, 1895.

Soon thereafter, a French military force marched toward Antananarivo, losing many of its number to malaria and other diseases as well as to Minuteman-like Hova sniping from the forests. Reinforcements had to be sent from Algeria and French Sudan. Upon finally reaching the city in September, the French column bombarded the royal palace with artillery pieces they had dragged up the hillside, causing heavy casualties, killing Henri, and forcing the queen to surrender on September 30. Ranavalona III was forcibly exiled, first briefly to Réunion and then to Algiers.

Waller was soon convicted of espionage in a summary proceeding conducted entirely in French. Wallerland was confiscated and declared an illegal concession. Since he was by this point a private U.S. citizen, the State Department did less than nothing on his behalf. Whetter sent cables assuring his superiors that Waller was doubtless guilty as charged. The French sentenced him to twenty years’ hard labor.

The French stripped Waller to the waist, chained his hands and feet to the mast of a French military vessel, and left open the hatch. Waller’s treatment paralleled a major rising of anti-Semitism in the context of the Dreyfus Affair, which started in December 1894 and was in full swing as Waller sailed from Toamasina to Marseille in the humiliating posture of a shackled slave. Exposed to the elements, Waller fell ill. He was thrown immediately into prison on April 21, 1895, where his health deteriorated further over the course of nearly ten months in captivity.

Waller might have died in prison had not the American Fourth Estate leapt to his defense, forcing the new Cleveland Administration to take action. Both the African-American and mainstream press took up the Waller Affair as an affront to American honor, making Waller perhaps the most famous African American of his day. Congress pressured the Administration, demanding hearings. Belatedly, the Administration responded, obstructed only temporarily by the fawning behavior of the new U.S. ambassador in Paris, James B. Eustis, “an avowedly Southern gentlemen,” as Barry Singer writes, “who viewed his role as a former slave’s advocate with extreme distaste.”

Using Waller as leverage, the French demanded U.S. recognition of their sovereignty over Madagascar and agreement not to support any indemnification suit regarding the confiscation of Waller’s concession. They would then release Waller as a goodwill gesture, without revoking his conviction.

To get the press and the Congress off its back, the Administration capitulated. (No one asked Waller if he would accept such conditions.) But then to deflect criticism of its capitulation, Secretary Gresham dragged out Whetter’s old accusations against Waller’s management of the consulate in an effort to offload their own pusillanimity onto him. Insult to injury, in other words. Eustis eagerly helped with a blatantly biased “report.”

The Vigor of a Free Man

A diplomat does not have to be a member of a minority group to be betrayed by his or her own government—ask Marie Yovanovitch for details—but in those days it helped. Nevertheless, when Waller exited a French prison on February 21, 1896, walking with a cane and his back slightly humped at the age of forty-six, his face aged almost beyond recognition according to a contemporary newspaper account, he “still walked with the noticeable vigor of … a free man.”

Waller returned to Kansas, put out his lawyer’s shingle, started a new newspaper, wrote and spoke widely, and campaigned hard for William McKinley. He hoped to be rewarded with the job of recorder of deeds for Washington, DC, the highest federal post an African American could aspire to at the time. No White Republicans supported him, however, and the job went instead to a White North Carolinian.

Yet Waller didn’t lose a step, soon becoming an ardent supporter of the Cuban revolution against Spain. When the Spanish-American War broke out, African Americans were still banned from military service despite their having fought for the Union in the Civil War. But Waller persuaded the governor of Kansas to let him raise his own company of African-American volunteers. As their uniformed commander, Waller himself led them to Cuba in August 1898. The company saw no combat but played a role in the U.S. occupation. Five months into the adventure, Waller summoned the family—including his young grandson Andriamanantena (now called Andrea or Andre, mercifully).

It’s not hard to guess what Waller was thinking. Having proved that African Americans would loyally bear arms on behalf of the United States, Waller saw Cuba as a substitute for the lost Wallerland—and a venture that White investors as well as African-American ones would now support. He created the Afro-American Cuban Emigration Society for the purpose and invested his own money in real estate around the town of Santiago. He expected both the U.S. military government in Cuba and the McKinley Administration to support his plan. They didn’t. The Afro-American Cuban Emigration Society never even rose to its knees, much less get legs.

Waller and family returned to the United States almost broke in September 1900. He returned to Kansas just long enough to sell the house and moved the family first to Manhattan and then to a modest home in Yonkers. His plan was to start another newspaper, hoping that on the East Coast enough readers would subscribe to make it commercially viable. Meanwhile, he eyed the Gold Coast (today’s Ghana) as yet another potential Wallerland. He did start a paper, but the Yonkers Progressive American ultimately went bust. Waller, the former U.S. consul to the Kingdom of Imerina, ended up working at the New York Customs House during the year before his death. Singer’s curt description of Waller’s passing cannot be improved upon:

On a Sunday afternoon in October 1907, after calling at the Mamaroneck home of his foster daughter, he attempted to walk the several miles home in a cold rain, contracting pneumonia. Within the week, at age 56, he was dead.

And of His Progeny

Andy Razaf grew up with, and in the image of, his maternal grandfather. He remembered him in his military uniform in Cuba, and he remembered the many stories his grandfather and mother told him. The musical talents and career of his mother’s stepsister Minnie, who performed professionally as a singer and wrote many songs, also doubtless inspired him. Both his grandmother and mother wrote poetry, and encouraged Andy to try his own hand at it. By age seven, Andy could keep perfect time, and before his eleventh birthday, he wrote his first poems.

It is no coincidence that among Andy Razaf’s hundreds of lyrics one was “Garvey! Hats Off to Garvey!” By the 1920s the precociously outspoken Razaf was an editor for Negro World, the official newspaper of Marcus Garvey’s Universal Negro Improvement Association. At the time, it had the largest circulation of any such newspaper in the world. His grandfather would have been proud.

It is also no coincidence that Razaf wrote the lyrics to some of the first African-American political protest music, at a time when lyrics held higher pride of place in musical culture than they came to later. That includes “Black and Blue,” the best known of them, but also “Li’l Brown Baby” and several others.

A special case is “We Are Americans Too,” the best known of more than a dozen patriotic songs Razaf wrote during World War II, and for which he received a commendation from the U.S. Treasury Department in October 1944. The lyrics resonate with John Louis Waller’s Spanish-American War patriotism and his reluctance to alienate useful White support. But that’s not how the lyrics were born.

Razaf wrote the original version of “We Are Americans Too” in 1940 for the Eubie Blake musical Tan Manhattan. But following in his grandfather’s left-footsteps, so to speak, Razaf wrote a protest song in which he mentioned the bigotry, even the lynchings, that African Americans had suffered. Blake was aghast when he saw the lyrics. He told Razaf that the show could not include a song that gave White people hell for treating African Americans so badly or else the show would never sell. They argued about it for some time, but in the end Blake and his associate Charles L. Cooke softened the lyrics anyway. The irony is that, after the war, “We Are Americans Too” came to be considered the anthem for African-American patriotism, and Razaf was lauded for it in its softened form. One can only imagine what John Louis Waller would have made of all that.

Andy Razaf died in 1973 at the age of seventy-seven, but in November 1951, at age fifty-six—his grandfather’s age when he died—he suffered sudden paralysis as the result of a much-earlier syphilitic infection migrating to his spine. The stroke didn’t kill him, but it presaged the acute pain that plagued him throughout his later years. Like his grandfather, however, Razaf never stopped despite the pain, the frustrations, and the eclipse of his fame. He kept writing lyrics and articles for the Negro and progressive press in a continuation of his 1920s efforts for Negro World.

In January, Richard Thompson Ford wrote in these pages, “James Baldwin, the prophet of Harlem, warned of the fire next time, but he also knew that black people love America more than America loves itself.” That really struck me, partly because it reminded me of a Razaf line from “We Are Americans Too”: “None have loved Old Glory more than we; Or have shown a greater loyalty.”

Both lines struck but also puzzled me, so I asked Ford a simple question: Why? “Look,” I said, “the formerly enslaved Children of Israel in the Bible famously long for the ‘fleshpots of Egypt’ when they’re stuck in the desert with only manna to eat. But they never say they love Egypt. I don’t get it, and I want to, please.” Here in part is his answer:

America is the only home Black people really have … and Black people have made America what it is as much as any other race; despite discrimination, slavery, Jim Crow, the culture is very much our culture. So we love it and we see its potential to live up to its professed ideals, to become what it promises to be. That’s worth fighting for.

It’s not for me to say, but in these days of simplistic, emotionalized answers to ingrained complex questions, when the burgeoning zero-sum mentality can think impatiently only in terms of eternal conflict and victimhood, the lives of John Louis Waller and Andy Razaf testify to the greater wisdom of Ford’s conclusion.

Both Waller and Razaf could unquestionably have claimed the status of victims by dint of accidents of birth and the bigotry they suffered during their lives. But neither embraced victimhood, broad-brush accusations of racism, or imagined helplessness. Both seized instead upon their talent to build a better future; each in his own way—and sometimes the same way—succeeded. All Americans are better off for it, whether they realize it or not.

The thorough raveling of White and Black in the making of American culture is, as the late Stanley Crouch insisted, gloriously permanent. It has been and will be what we, all entangled together, make of it. We must never tire of trying to make it better, and as we try, the stirring stories of those who have gone before, like Waller and Razaf, form an ensemble of what amounts to an anthem. These are not stories with simple happy endings, but stories like that aren’t very useful. Useful stories must be true stories, and truth often carries today’s pain to invest in tomorrow’s gain. As Andy Razaf wrote in “Baby Mine:”

I’m laughin’ at sorrow

He’s knockin’ in vain.

I welcome tomorrow,

And smile at the rain.

Adam Garfinkle, an editorial board member of American Purpose, is unemployed.

1Sources differ as to whether Waller’s middle name is spelled “Louis” or “Lewis.” As to the relevant historiography, plenty exists about Razaf intermixed with the history of American jazz, but only one serious biography examines Razaf’s family origins: Barry Singer, Black and Blue: The Life and Lyrics of Andy Razaf (1992). On Waller there exists a privately published 52-page biography by Estelle A. MacNaughton from 1913, entitled Life’s Phases, and Randall B. Woods’s A Black Odyssey: John Lewis Waller and the Promise of American Life (1981). Woods never mentions Andy Razaf or anything that happened after Waller’s death. Finally, a relative of Waller’s, David M. Talley, created a one-hour documentary in 2009, “Striving for Equality,” based largely on Woods’ book. No other secondary literature on Waller seems to exist. Otherwise, details of “the Waller Affair” in this essay can be gleaned from newspaper archives from the 1896–97 period and from some lean documentation in the Department of State Archives.

2This fact of free African Americans owning African-American slaves in antebellum America is brilliantly plumbed in Edward P. Jones’s award-winning 2003 novel, The Known World.