Gradual Change is F***ing Awesome—And Liberalism Knows It

On Darwin, abuse, and Costanza politics.

WHY LIBERALISM

“Why Liberalism” is a series by Persuasion in collaboration with the Institute for Humane Studies. Last year, we ran six pieces by journalists and philosophers making the case for philosophical liberalism at a time when its foundations were under attack from just about everyone. This year—when, it’s fair to say, we have more convincing to do than ever—we’re doing another round, starting with this tour de force by a longstanding member of the Persuasion community: Wayne Karol.

Wayne takes us on a (deeply personal) journey through high and low culture, Obama and Seinfeld, to make the argument that liberalism’s “slowly, slowly” approach of adaptation and reform is still the most miraculous social technology humans ever came up with. We couldn’t think of a better way to launch the next round of our series.

Seriously, you’re going to want to read this one to the end.

– Luke, series editor.

“If I’m right, the system by which we judge humans, the very method we use to deem them good or bad is so fundamentally flawed and unreasonable…”

Michael, The Good Place

I

If I became the Boss of Liberalism, the first thing I’d do is tell the people who want a politics centered on demonizing rich people and the people who want a politics centered on demonizing white people that the fight is over, and you both lose. From now on, the enemy is abusive people. (If they need an explanation, Donald Trump is rich, white, and abusive. Which one is the problem with him?) From this moment forward, liberalism’s mission is to make the world less abusive. At a time when liberalism is struggling to remember what it’s supposed to be about, it connects us both to our roots (Judith Shklar locating liberalism’s origin in the belief that cruelty and the fear it causes are the worst evil) and to the current crisis (the most on-target description of Trumpism is still Adam Serwer’s “the cruelty is the point”).

You’ll hear a lot of accusations made against liberalism. Focusing on abuse can help us answer the accusers. Liberalism’s left us lost in a lost world where nobody knows how to find moral purpose or even understands why they should? Here is as good a moral mission as you could ask for. Liberalism’s made us too individualistic? Here compassion for what others are going through is what it’s all about. Liberalism’s too quick to hand members of traditionally oppressed groups a moral blank check to be abusive themselves? Here’s a principle that tells us why we shouldn’t. Liberalism speaks in an esoteric language that “regular” people can’t relate to? “Abuse” is a term that anyone can understand. Liberalism’s become so focused on separate “identities” that it’s lost a sense of common ground? Surely there’s enough abusiveness in the world to make a big and flexible tent.

We’re also told that society’s increased focus on abuse and trauma has become a cure worse than the disease, that it’s given our kids an excuse to be both slackers—“Making me accept normal human responsibilities would retraumatize me!”—and bullies—“Questioning a word I say would retraumatize me!” I’m reminded of a quote in a book called Woodstock Census, which describes the Sixties as “an awakening, and like all awakenings it was groggy and stupid.” There’s no denying that the awakening that’s been happening the past few decades about the prevalence and damage of abuse and trauma has had its share of grogginess and stupidity; if you’ll excuse me indulging in some “identity politics” of my own, as a survivor of childhood trauma it infuriates me when the language of trauma is hijacked to shut people up. But do not, DO NOT try to tell me that it was a better world when one of America’s most legendary generals thought that soldiers with PTSD are cowards who deserve to be slapped around, when the first rule of sexual abuse was that you do not talk about sexual abuse, when the psychiatrist I was sent to when I was 14 tried to pressure me into reading Oedipus Rex because I was constantly fighting with my father.

Of course, every movement needs an inspirational manifesto, and I doubt I can do better than to direct you to a piece by Noah Smith. Ostensibly about the life and death of his pet rabbit Cinnamon (find someone who loves you as much as Smith loves rabbits), it makes the best case I’ve ever seen for what could be so emotionally powerful about (though he uses neither word) a liberalism based on opposing abuse. I’m just going to quote two paragraphs, then advise you to check out the rest of “Why rabbits?”:

Nature endows some people with strength—sharp claws, size and musculature, resistance to disease. Human society endows us with other forms of strength that are often far more potent—guns, money, social status, police forces and armies at our backs. Everywhere is the tendency for those with power to crush those without it, to enslave them, to extract labor and fealty and fawning flattery. ‘The strong do what they can, and the weak suffer what they must’, wrote Thucydides; this is as concise a statement as you’ll ever find of the law of the jungle, both the real one and the artificial jungles humans create for themselves. A hierarchy of power and brutality is a high-energy state, an easy equilibrium toward which social interactions naturally flow.

I believe that it is incumbent on us as thinking, feeling beings—it is our moral purpose and our mission in this world—to resist this natural flow, to stand against it, to reverse it where possible. In addition to our natural endowments of power, we must gather to ourselves what additional power we can, and use it to protect and uplift those who have less of it. To some, that means helping the poor; to others, fighting for democracy or civil rights; to others, it simply means taking good care of their kids, or of a pet rabbit. But always, it means rolling the stone uphill, opposing the natural hierarchies of the world, fighting to reify an imaginary world where the strong exercise no dominion over the weak.

Now that’s a mission statement!

II

Or is it? If this world is abusive and that’s just the way it is, isn’t trying to change it a naïve idiot’s delusion? If our arms are too short to box with reality, shouldn’t we have the honesty and the courage to face up to that fact?

If only there was some evidence that liberalism understands how reality works better than its critics! Like, for example, the evidence that’s been sitting in front of us for the past 150 years. The evidence that’s been called “the best idea anyone ever had.” The evidence that we’ve agreed to confine to its designated turf—the biological sciences—and not listen to anything else it has to tell us. That too needs to change.

Let me illustrate with an example. The Affordable Care Act wasn’t easy to love. It’s complicated, too full of systems and subsystems to be reduced to an easily graspable slogan. It certainly wasn’t the sort of out with the old, in with the new that many people think of as “change.” It prompted a lot of “Obama promised change, what the hell kind of change is this?” Here’s what kind: the kind that was capable of surviving the political and economic environment it was in. That started with the existing health care system and created something which descended with modification from it. That took existing systems (Medicaid and Romneycare) and expanded their functions.

The ACA wouldn’t make sense in a world where perfect health care without difficulties or tradeoffs was available as a universal blessing. We don’t live there. Neither do we live in a world where nothing ever really changes and you just have to take what’s dished out to you. In this world, change is an essential part of how it works—always partial, always imperfect, but under the right circumstances it can turn out to be a big fucking deal indeed.

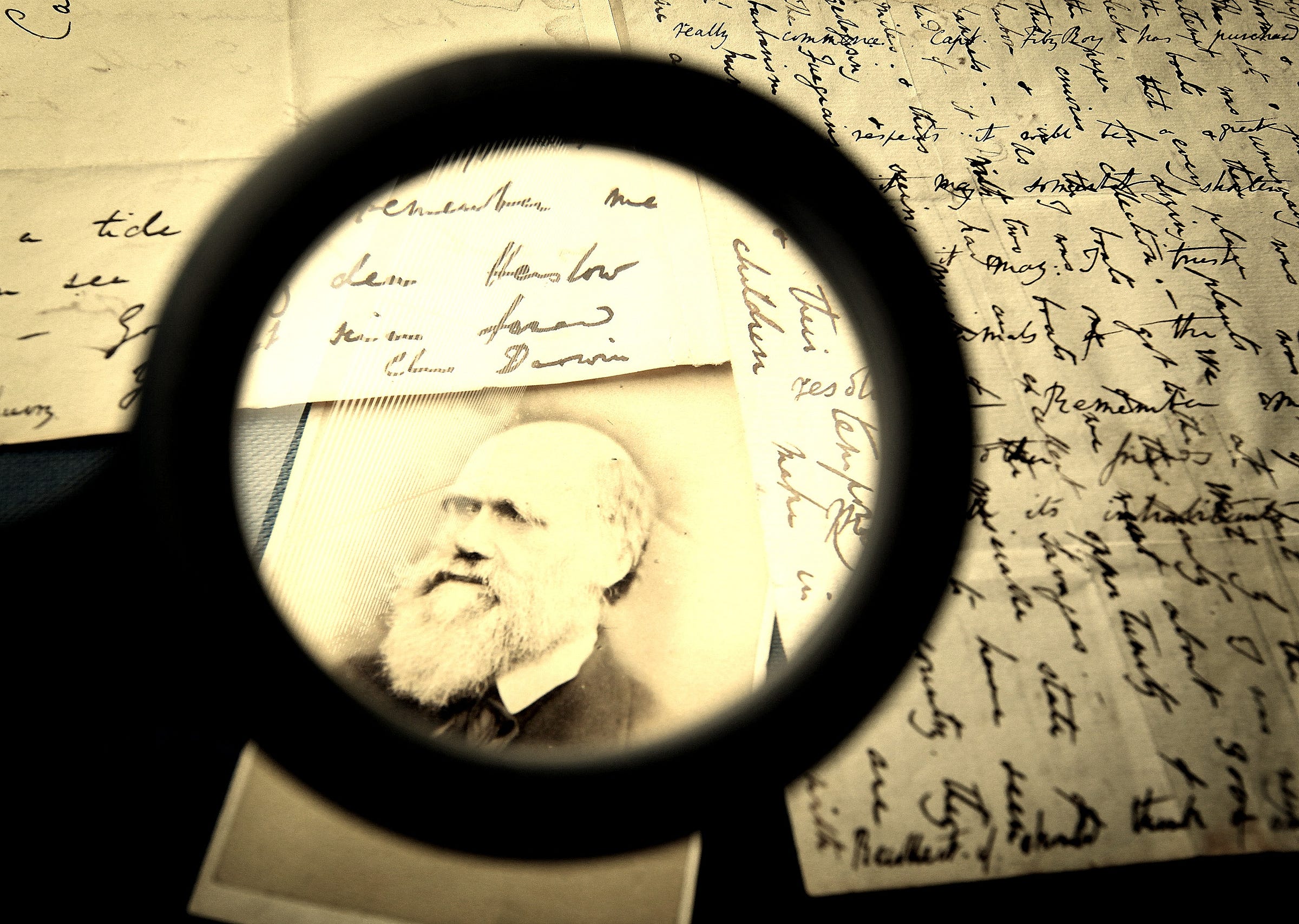

Yes, I’m claiming evolution for liberalism. Not just because that’s the side the culture wars have assigned it to, or because out of modernity’s Big Thinkers Darwin has held up in a way the Marxes and Freuds haven’t, or even that it’s because their societies had liberalized to the extent they had that Darwin and Alfred Russel Wallace were able to get away with it rather than being burned at the stake. (Let me repeat that: burned at the stake.) Theodosius Dobzhansky famously wrote that “nothing in biology makes sense except in the light of evolution.” What I’m saying is that the case that beings as flawed as humans deserve the rights and freedoms and dignities that liberalism promises us all makes a hell of a lot more sense if you know our true history than it would if we really were children of some perfect Eden.

If you tried to sum up natural selection in one sentence, it might go something like “Species became what they are to survive the environment they were in.” Isn’t that the same thing we tell people who were abused as children?

III

If there’s one sentence in this essay that I want people to remember and repeat, it’s this: Darwin is Robin Williams in Good Will Hunting, telling humanity it’s not our fault.

The modern concept of abuse wasn’t part of Darwin’s culture, but if you look at what he wrote privately, to people he trusted, it’s clear that he got it. To Asa Gray:

I own that I cannot see as plainly as others do, and as I should wish to do, evidence of design and beneficence on all sides of us. There seems to me too much misery in the world. I cannot persuade myself that a beneficent and omnipotent God would have designedly created the Ichneumonidae with the express intention of them feeding within the living bodies of Caterpillars, or that a cat should play with mice.

Let that sink in: there’s a species of wasp that lays its eggs inside a living caterpillar, and when the larvae hatch they eat the caterpillar alive. That’s Nature, that’s the world we had to adapt to. Darwin was willing to see the cruelty, the abusiveness of the natural world without flinching. Perhaps just as important, he was willing to take the step that’s so essential for someone who’s trying to heal from abuse. He was unwilling to accept that somehow, some way, there had to be some sort of rightness to all that suffering. He refused to legitimize it. Oh yeah, he got it.

What’s the moral of Darwin’s story? That it’s not our fault that we’re children of a universe that’s violent and destructive on a scale so far beyond human experience that explosions that would massacre every living being for light years around are just part of how it is. It’s not our fault that we’re children of a solar system so inhospitable that life couldn’t make it even on the planets that Earth has the most in common with. It’s not our fault that we’re children of a planet that began as what can only be called Original Hell. It’s not our fault that we’re children of creatures who even when they were dinky little bacteria caused what’s been called “the greatest pollution disaster ever to afflict our planet.” (The poison was called oxygen. It killed an unimaginable number of beings before life adapted.) It’s not our fault that we’re children of early mammals who had to be nocturnal because if they showed their furry faces during the day they were too small and weak to stop dinosaurs from chomping on them. It’s not our fault that we’re children of early humans whose existence was so precarious that at one point around 900,000 years ago there were fewer “reproducing individuals” than the number of people I went to high school with.

A lot of people are saying that liberalism needs to embrace patriotism, that it’s normal for people to want to be proud of their country. I have no quarrel with that, but how about a little species patriotism? When other species are caught in a downpour they have no choice (unless they’re lucky enough to be near some sort of natural shelter) but to get soaked to the bone, weakened, less able to fight off predators and pathogens. Not us; we build our own shelters and stay nice and dry while the wind howls around us. Warm, too; fire is one of the most dangerous things on this planet, and we figured out how to use it to help us stay alive. How’s that for impressive? The climate has changed and we can’t feed ourselves by hunting and gathering? Fuck it, we’ll grow our own food! When we got sick we didn’t just lay down and die; we checked out every plant in the area till we found the ones with medicinal properties. Think of the effort that took. Think of the courage, since some of them were surely poisonous. Now think about what it took, in a nonliterate society, to keep track of which plant helps with what disease, in what doses, with what side effects, and to accurately pass that knowledge from one generation to the next.

That’s humans. That’s what we’re capable of. If we can’t find something to take pride in here, something is very wrong.

And we’ve kept on doing it. I’m certainly (more than) old enough to play “When I was a kid”; so let’s test the hypothesis—popular on both left and right—that everything sucks and it’s only getting worse. When I was a kid it was rare for people to live into their nineties, now it’s common. How’d we get so convinced that we’re the unhealthiest culture ever? When I was a kid only 12% of American homes had air conditioning and 16% didn’t have complete indoor plumbing facilities; why are we so nostalgic for the economy of those days? When I was a kid half the people in the world lived in extreme poverty, now it’s less than ten percent. Maybe globalization’s not so bad? When I was a kid we were beginning a thirty-year crime wave, and then it dropped just as dramatically. Why do “more than two-thirds of Americans believe that crime has been getting worse, year after year”?

When I was a kid, millions of black people still lived under an oppression that was as vicious as it was ridiculous. (I mean, segregated water fountains? Seriously?) When I was a kid (or maybe a little before), “institutionalization and sometimes electric shock treatments were used to force women to accept their domestic roles and their husbands’ dictates.” When I was a kid, “If my kid was queer I’d fuckin’ kill him” was considered normal. Why do we find it so easy to believe that in the old days we had morals and values that we’ve degenerated from?

So when left-wing illiberalism tells us we haven’t really changed anything, and right-wing illiberalism tells us we’ve only made everything worse, why aren’t we shoving what we’ve accomplished in their smug faces? Why can’t liberalism take a fucking win?

I’ve got a hypothesis. One of the most frustrating things about healing from abuse is that when you’ve made progress at dealing with an issue, often your reward is that it’s time to deal with a tougher one. An alcoholic quits drinking, now you have to find other ways of dealing with what the booze helped keep under control. Break off a relationship that’s no good for you, now you have to figure out what you do want and how to get someone like that. It takes time and figuring out, and sometimes you’re going to make mistakes.

Liberalism too has found that the price of solving problems can be the creation of (hopefully smaller) ones. Create an economy that produces unprecedented prosperity? Now you have to deal with the pollution that comes with it. Free people from the fear and insecurity of authorities being able to beat the shit out of you at whim? Now you have to figure out how you are going to keep order when you need to. When you find yourself moving to a deeper level, it’s not unusual for the difficulties to make you feel like you can’t do it, you’re not good enough, you haven’t really accomplished anything. It’s important to remind yourself (or, more likely, have other people remind you) of all the reasons why that’s not true. If that’s where liberalism is at, it’s important that we change the narrative. Like, now.

IV

How many times in the past ten, or fifty, or a hundred years have we been told that the problem with liberals is that we’re so centrist?

We wouldn’t be so easy for leftists to guilt-trip into being more radical than we really want to be if we’d remember that that’s a feature, not a bug; as Paul Starr noted in Freedom’s Power, “Through the mid-twentieth century, liberalism occupied the political center, offering a middle way between communism and socialism, on the left, and conservatism and authoritarianism, on the right.”

When’s the last time you heard anyone make a case that that’s a righteous place to be? Not a practical place, good for winning elections in a divided country, but a place where a moral, principled person should want to stand, where you could see yourself telling an idealistic young person that that’s where they should want to be?

When they tell us that centrists are unprincipled cowards, easy to push around and quick to “compromise” (i.e. sell out) with Evil, we don’t have a language to tell them why they’re wrong. We don’t have a way to get out of this bizarre situation where the sort of people who vote in general elections prefer moderates, while those who vote in primaries believe that extremism is no vice and moderation no virtue.

If liberalism is seen in the light of evolution, that should be no surprise. Humanity’s basic moral template is still a creationist worldview that doesn’t know how to make sense of liberalism.

The most popular name for that worldview is “moral clarity” (a term that’s a favorite of both Sean Hannity and Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez), but I prefer to call it “polarized morality.” It tells us that the universe is a battleground between two utterly opposing, utterly different forces (and don’t you dare suggest that there’s any moral ambiguity about it): Good and Evil, Right and Wrong, God and Satan, whatever you want to call them. That you can draw a nice neat line between them as easily as choosing sides on the playground, and it’s everyone’s moral duty to, as they said on The Colbert Report, “Pick a side! We’re at war!” And that if you choose Good, you’re committing yourself to wage a war of extermination against Evil. Thou Shalt Utterly Destroy Them, period, no ambiguity. Anything less and you’re a traitor and should be treated like one.

That’s the morality you might expect if we are the creation of an Ultimate Ruler with the right and the power to hand down Absolute Rules. What it seems utterly incompatible with is liberal democracy. How would it make any sense to permit freedom of expression if we can be certain of what’s right and what’s wrong? (As the pre-Vatican II Catholic Church used to say, “Error has no rights.”) Basic tools of democracy like negotiation and compromise and dealmaking would amount to moral treason, the equivalent of telling Hitler, “Okay, I’ll agree to you killing three million Jews, but that’s where I draw the line.” And of course the idea that there could be times when something more moderate could actually be better than something more extreme would be self-evidently absurd; as Ayn Rand’s John Galt put it, “There are two sides to every issue: one side is right and the other is wrong, but the middle is always evil.”

If that’s how the world works, the success of liberal democracy would be hard to explain. So maybe that’s not how the world works? Let’s start with economics. If polarized morality is true, the ideal economic system would be either capital-C Capitalism or capital-S Socialism, all market or all government. And yet for the past century or so, the real world has made it quite clear that capitalism modified by ideas that originally came from socialists (in their various forms) has given people better lives than either straight capitalism or actual socialism. When liberalism’s answer to “More government or more market?” is “It depends on the circumstances,” it’s not because we’re a bunch of squishes who don’t have the balls to pick a side, it’s because that’s the right answer!

If polarized morality is so out of touch with reality, how did it get so dominant? I’m going to speculate. I can think of one situation where it would have a survival advantage. If you’re in the middle of a physical fight where only one of you is going to walk away alive, that’s not the time to be considering whether your opponent has a legitimate grievance against you. If thinking of the other guy as Pure Evil helps motivate you to feel like you have to win this fight, that just might give you an edge.

But you know when that attitude’s not a good thing? If you’re around your family or friends or neighbors or coworkers still feeling like you’re locked in a kill-or-be-killed struggle, ready to explode at the slightest microprovocation. Most of life isn’t a death match, and you need to be able to shake it off (literally, that’s the physiological reaction which tells our body that it’s over) and go about your life. Polarized morality tells us that it’s never over, that it’s realism to stay traumatized, that The Enemy is always lurking, ready to get you unless you get them first. And it’ll tell you whatever lies it needs to keep you there.

Many of us, hopefully most, do manage to unlearn it to some extent. We realize that life and people are more complicated than is dreamt of in polarized morality; that “The kindest person you ever meet will have some moments of cruelty in their life; even the most upright and honest bend the rules once in a while; even people fighting for noble causes will have times when they’re selfish, arrogant, and greedy.” But only partly: polarized morality has been so drilled into us that dislodging it is no small effort. Besides, it’s what we know; for all its faults, wouldn’t it still be better than moral anarchy? What are we supposed to do instead?

I’m sure people used to fear that the only alternative to absolutist rule was political anarchy, and liberal democracy proved that wrong. There are other visions out there, from yin and yang to the ancient Greek “nothing to excess.” If you prefer something more modern, perhaps the wisest way of looking at it I’ve ever found is from an obscure book from the early Eighties, Charles Hampden-Turner’s Maps of the Mind:

It is in vain that we search for an essential difference between good and evil, for their constituents are the same. The crucial distinction lies in the structure; i.e. the manner in which the pieces are assembled. Evil is disintegration, an angry juxtaposition of alienated opposites, with parts always striving to repress other parts. Good is the synthesis and reconciliation of those same pieces.

And if you want a version that fits on a bumper sticker, here’s Buckminster Fuller: “We walk right foot, left foot, not right foot, wrong foot.”

But theoretical constructs only get us part of the way. Humans need examples, role models, someone who’ll live the values they preach, show us how it’s done. If we asked Central Casting for someone like that, what would they send us? Given polarized morality’s ubiquity, the only way it would be believable is if this was someone who’d led a life where polarized morality wouldn’t have worked for them, who had to synthesize and reconcile so many seeming opposites that the only way to be themself was not to side with one pole and reject the other. Of course you’d want someone with star potential, the sort of charisma that makes them easy to like and impossible to ignore. And wouldn’t it be a cool twist, in keeping with the reconciling-of-opposites theme, if they were somehow part all-American and part exotic?

Yeah. Him. The most successful liberal politician since at least LBJ, if not FDR. The one who consistently ranks at or near the top of surveys of most popular political figures (which is even more impressive given that there’s no shortage of people who hate him). The one who started to take America a few tentative steps toward an alternative to polarized morality (I believe another word for that would be “change”), only to have the public not understand what he was doing, get scared and confused, and run back to the comfort of the familiar, leading to a politics where polarized morality was back with a vengeance. Literally.

In the years to come he would often be compared to Mr. Spock, but one of the things that made him the Barack Obama so many of us fell for that night in 2004 is that this was a Spock at peace with both his Vulcan and human “halves.” Black and white, Kenya and Kansas, South Side Chicago and Harvard Law—it’s like he was a living embodiment of e pluribus unum. What’s more, he also harmonized his personal history and “the larger American story … in no other country on Earth is my story even possible.” He offered us a way out of yet another polarization that we’d taken for granted since at least the Sixties: that wanting to be proud of America and wanting to make America a fairer, more compassionate place put you on opposite sides. That’s not how Obama saw it. How had America gone from a land of slavery and Jim Crow to one that was willing to elect a black man with a name like Barack Hussein Obama?

Because (as he loved to put it) making “a more perfect union” is how America’s supposed to work. His Selma speech is one of the best examples, joining John Lewis and Lewis and Clark, “the fresh-faced GIs [in World War II] who fought to liberate a continent” and “the Tuskegee Airmen and the Navajo codetalkers and the Japanese Americans who fought for this country even as their own liberty had been denied” into a single this-is-us story. He made a division that had defined American politics and culture for half a century sound so unnecessary! At the same time, he made the central claim of polarized morality—that (in Mónica Guzmán’s words) “all these people on the other side want me to be hurt because they are crazy, stupid, or evil”—seem like the lie that it is.

V

I’m a baby boomer. I expect you to know your Vonnegut.

In the novel Cat’s Cradle there’s a concept called a wrang-wrang: someone who provides a negative example to warn you away from. The principles of liberalism weren’t handed down from On High; they evolved in reaction to its environment, and some of its defining moments have come in response to wrang-wrangs. Time after time, a form of abusiveness that (almost) everyone had taken for granted was taken to such a horrible extreme that it seemed like a moral obligation not only to oppose it, but to define your sense of right and wrong around opposing it.

For Liberalism 1.0, the wrang-wrang was the European Wars of Religion. The belief that there’s only one legitimate religious belief, and if someone believes differently it’s your moral obligation to hate and kill them, had been a cornerstone of Judeo-Christian-Islamic faith for thousands of years. It was the rule in Europe for more than a millennium, and as bloody as it got at times, it was accepted that that’s just how things are. But this time the death toll was so huge—it’s been estimated that Germany lost a third of its population—that people realized this has got to stop, and the way to stop was to respect people’s right to decide for themselves what the right way to worship was. And from that seed grew freedom of speech, freedom of the press, freedom of assembly, the right to self-government, the right to be an individual, to define yourself rather than let your family or tribe dictate who you are. The world would never be the same.

Liberalism 2.0’s wrang-wrang was, of course, the Nazis. It’s not like the gap between what America preached and what it practiced regarding “All men [sic] are created equal” wasn’t obvious, but we’d already been through one civil war; do you really want to risk another? So even people who didn’t like it came up with rationalizations that let them live with it—until the Führer reminded people what racism can lead to, and a critical mass of people went okay, THAT’S why we shouldn’t tolerate it.

The timing is too close to be coincidence; the single decade from 1945 to 1955 included Jackie Robinson signing with the Dodgers, Harry Truman desegregating the armed forces, the 1948 Democratic Convention splitting over civil rights, Brown v. Board of Education, and the Montgomery bus boycott. And from that seed grew the rest of what Steven Pinker calls “the Rights Revolutions”—all sorts of groups who had been traditionally branded bad or inferior rising up to demand their place in the sun. Let me give just one example of how much that changed things: we went from a country where even a president as liberal as FDR was willing to imprison people in camps for having the “wrong” ancestry to a country where even a president as conservative as Bush was not.

And since People Are Saying that liberalism could use some rethinking, who could make a better wrang-wrang for Liberalism 3.0 than Donald Trump?

For someone who lies so constantly, it’s remarkable how transparent Trump’s been about how he sincerely believes the world works: 1) There are only two ways that two people, or two races, or two genders, or two countries can relate to each other: either you’re dominant and the other guy is submissive, or the other guy is dominant and you’re submissive (I’ve taken the liberty of substituting more accurate terminology for “winner” and “loser”). Therefore, anyone who doesn’t submit to your dominance can only be trying to dominate you. If your dominance is less than absolute, the other guy must be taking advantage of you, humiliating you, laughing at you. Therefore, anyone who refuses to submit to your dominance is the aggressor, and anything you do to them can be justified as self-defense. Anything.

What sort of people would be attracted to a message like that? Matthew MacWilliams did a study of Trump supporters way back in December 2015. These weren’t the people who voted for him because they’re loyal Republicans or they didn’t like Hillary or they were pissed about inflation or immigration or wokeness. These were the hardcores, the people who felt like Trump was telling it like it is and liberating them to do the same. MacWilliams “found a single, statistically significant variable [which] predicts whether a voter supports Trump—and it’s not race, income, or education levels: It’s authoritarianism.” Read a little further, and you’ll find that political scientists define authoritarianism by support for authoritarian parenting: whether or not they think each of the following is more important: “1. Respect for authority vs. independence; 2. Obedience vs. self-reliance; 3. Good manners vs. curiosity; 4. Being well-behaved vs. being considerate.”

Ask believers in authoritarian parenting why that’s so important—those are a lot of good qualities that they’re willing to sacrifice to submissiveness—and they’re likely to tell you that if you don’t establish dominance over your child they’ll end up dominating you. (One of my father’s yelling-cliches when we were fighting was “I’m not going to kowtow to you!”) News flash: parents have far more power—physical, financial, knowledge and experience—than children. If the stronger are afraid of being dominated by the weaker, someone is out of touch with reality. It can only make “sense” if you fear that anything less than absolute domination is weakness. No wonder they like what Trump’s selling.

But while Trump will always have the hardcores, the people who decide the elections and the culture of the next few years are going to be those who want something different. So with apologies to Mr. White, it’s very important that liberalism doesn’t stink. Let me close, then, with a few areas where a liberalism seen in the light of evolution and abuse might want to do some rethinking.

VI

The indictment against “liberal elites” has become so popular that you’ll even hear it from many liberals. We’re smug, self-righteous know-it-alls, convinced that we and we alone know The Way of Righteousness. We preach diversity, while we tell everyone how they must live and think and speak. We preach tolerance, while viciously condemning and canceling anyone who dares to suggest we might be wrong about anything. We preach compassion, while looking down our noses at the Sainted Working Class. We’re so sickening that even the groups that used to vote liberal, from “people of color” to young people, have had enough of us. Why Trump? Because we provoked Normal Americans to send him after us, to give us the ass-kicking we so richly deserve.

How do I plead? The Nixon Defense: everybody does it. When’s the last time you encountered a belief system that wasn’t contemptuous of those who are too stupid/corrupt/evil to see that they’re so obviously right? But the paradox of liberalism is that we lose what does make it a better way of living in the world if we’re too smug about it. Just as the way to make America a more perfect union is to recognize what we’ve done wrong and act to change it, a more perfect liberalism requires doing the same, which means listening to people who tell us we’re wrong. That’s why people who are wrong more often than they’re right are still entitled to freedom of speech. Because nobody’s anti-perfect.

If you’ve found something that helps you with healing, it can be tempting to believe that it’s the answer to everything. For a long time, the desire to shove the blessings of liberalism down the throats of “uncivilized” people for their own good was one of liberalism’s major moral failings. John Stuart Mill, Mr. Liberalism himself, called British rule over India a “blessing of unspeakable magnitude” for the shovees. The liberal alternative to “The only good Indian [sic] is a dead Indian” was Great White Father “civilizing” his red children. It’s an attitude not all that different from O’Brien telling Winston in Nineteen Eighty-Four: “We shall squeeze you empty, and then we shall fill you with ourselves.”

Modern liberalism has done an admirable job of rejecting (at least the old-school version of) that attitude. The progressive overcorrection (putting “indigenous” people on a pedestal and so on) doesn’t change the fact that the correction was absolutely the right thing to do, and it happened because liberalism was willing to listen to criticism and respond to it. Are we doing something to make conservatives feel like we’re out to squeeze them empty? If so, we should stop.

And you don’t need me to tell you that liberalism needs to clearly and firmly reject what went so terribly wrong on the left of center over the past decade or so. The thing is that we need to do so in a way which shows that we get what was wrong with it, that we’re not just saying it to get votes, and we need to give a liberal perspective on why it was wrong, not a lite version of the conservative attacks on it. I’ve got an idea. A name for it which shows that we get it in a way that calling it “wokeness” or “critical race theory” or even good old “political correctness” does not: Costanza politics. Its basic premise was the same as the episode of Seinfeld where George decides to do everything by opposites. And it worked about as well as a typical Costanza scheme.

In Moral Politics, George Lakoff wrote that conservatism includes a concept he calls the Moral Order: the belief that some people and groups are naturally entitled to moral authority over others—or, as I prefer to put it, that some people and groups are morally entitled to receive submission from others. He also notes that in liberalism, “The priority given to Fairness overwhelms Moral Order. There is virtually no place left for it to apply, except in the religious instances where God has moral authority over human beings. Among human beings, it disappears.”

That’s one way you could deal with it if you find conservatism’s Moral Order to be unfair and oppressive. Another would be to figure that if conservatism’s Moral Order is wrong, “then the opposite [Moral Order] would have to be right.” (Jerry’s line just might be one of the best single-sentence summaries of polarized morality ever.) Blacks would therefore be morally entitled to receive submission from whites, women from men, gays from straights, trans people from cis people, nonhumans from humans, the non-West from the West, the poor from the non-poor, the disabled from the abled, the homeless from the housed, criminals from the law-abiding, Them from Us—and we can be sure there’s more to come, since one of the best ways to make a name for yourself in Costanza politics academia is to find new ways to add to the list!

That’s why “antiracism” managed to recap exactly what people healing from abuse should not do, from refusing to acknowledge the progress you’ve made to accusing anyone who doesn’t give you blind, unquestioning support of betraying you to acting like your abuse history is a moral blank check, that you’re free to commit your own abuses and still entitled to a victim’s (to use one of Costanza politics’s favorite words) privilege. To bring it back to Darwin: it’s like they were choosing to adapt to an environment that no longer exists. Given what often happens to species that are in that situation through no fault of their own, if your concern is “Black survival,” to choose to put yourselves into such a survival-endangering milieu is downright, well, Costanza-like. And we’re living with the results.

Of course, there’s considerable evidence that diversity really is our strength. One researcher found that diverse groups were better at decision making than smarter but monolithic ones. Another put together mock juries, some all-white and some racially mixed, and found that the diverse ones “considered more potential interpretations of the evidence, remembered information about the case more accurately, [and] engaged in the deliberative process with more rigor and persistence.” As Steven Johnson put it, “We are smarter as a society—more innovative and flexible in our thinking—when diverse perspectives collaborate,” and that’s true whether the diversity is racial, gender, or “professional, economic, and intellectual.”

My point is that diversity only works if the different perspectives do collaborate, otherwise it’s the story of the blind men and the elephant, at war over partial perspectives claiming to be The Truth. And while our spiritual imaginings tend to feature One All-Seeing Eye as if that’s all we need, natural selection has chosen differently; we see right eye, left eye, not right eye, wrong eye.

That’s liberalism’s ultimate insight. No one is the one and only Light Unto the Nations. No one is Swami Rabbitima (“Knows All, Tells All”). That means we have to work harder to figure out how it really is; it also means that nobody has to be squeezed empty.

That’s not a bad tradeoff.

Wayne Karol is the author of “The Sixties as Science Fiction: An Appreciation of Paul Kantner.”

The “Why Liberalism” series is a project by Persuasion in partnership with the Institute for Humane Studies (IHS). IHS is a non-profit organization that promotes a freer, more humane, and open society by connecting and supporting talented graduate students, scholars, and other intellectuals who are advancing the principles and practice of freedom. For additional information and details, media, programmatic, and funding opportunities, visit TheIHS.org.

Follow Persuasion on Twitter, LinkedIn, and YouTube to keep up with our latest articles, podcasts, and events, as well as updates from excellent writers across our network.

And, to receive pieces like this in your inbox and support our work, subscribe below:

No, Trump is not abusive, he is an overt narcissist... a typical self-confident male leader.

His directness seems like abuse to the covert-vulnerable narcissists.

The difference is that we can deal with Trump's criticism because it is direct. We can come up with arguments against his criticism if we disagree. We can have confidence that he is not hiding any agenda... he just says what it on his mind and his actions generally completely match his words.

If we are going to eliminate the worst type of abuse, it would be the covert/vulnerable narcissist type. These are people that put on a fake face while hiding their real intent and agenda... which is usually one of resentment to destroy any in their way... any daring to criticism them or oppose them.

The problem with modern left-liberalism is that it has become the safe space for the covert/vulnerable narcissist. People that think they are little Gods that should rule the world, but will never admit it to your face... only work to stab you in the back until you are bloody and dead while they take your resources and position because they, of course, believe they deserve it.

Kudos for a far-reaching, clear and engaging account of liberalism versus its antagonists across (a reasonably abbreviated portion of) history. No "master narrative" can account for all historical evidence ("Life is not simple, and therefore history, which is past life, is not simple.) Wayne Karol's essay here offers a powerful story knitting liberalism's essential strengths to key other stories (the evolution of life, the wars of religion, U.S. race relations, Nazism, capitalism, cancel culture, Trumpism, and child abuse) and showing why gradual reformism can be, and often has been, the more successful, durable strategy. Liberal/progressives need just this kind of narrative, and the implicit arguments it incorporates, to help our fellow citizens conceive of a "big picture" alternative to the phantasmagorical vision of "American carnage" so dishonestly and self-servingly promoted by Trump and his clique of opportunists.