History: The Dictator’s Plaything

More and more Americans are catching on to what dictators have always understood—the importance of controlling the historical narrative.

America has belatedly learned that it is no longer invulnerable to the anti-democratic currents advancing around the world. While the United States may still be the land of the free, its trajectory is moving in the wrong direction; on the Freedom House scale, America now ranks among flawed democracies like Croatia and Italy rather than the United Kingdom or Germany.

America’s democracy deficit is homegrown. But the erosion of our institutions takes place in a world dominated by the spread of autocracy; the growing self-assurance of strongmen; the development of methods of political control that are nuanced, flexible, and strategic; and a transnational autocrats’ network that trades in influence, ideas, and “best practices.”

Modern authoritarians have developed the means to control the commanding heights of the media, the mechanisms of elections, the police and military, civil society, minority groups, and the economy. More recently, they have focused on another crucial category of democratic life: history and culture.

In autocracies large and small, brutal and relatively relaxed, historical revisionism has emerged as a regime priority nearly as important as crony capitalism or control of the judiciary. Modern strongmen demand a new national narrative because the old narrative raises uncomfortable questions about the leader’s legitimacy. Today’s autocrats and aspiring autocrats (think Poland) routinely use the highly charged term “traitor” to demonize their adversaries. They attack opposition figures not because they are leftists or archconservatives but because they are not “real” Turks, Hungarians, or Russians. What defines a real Turk, a real Hungarian, a real Russian? The new history is meant, in part, to serve as a point of reference from which to pass judgment on the patriotism of individuals, whether they be opposition politicians, uncooperative business owners, independent-minded schoolteachers or poets, or citizens who’ve come out as gay.

Vladimir Putin is the master of modern historical falsification. In 2007 he launched a sweeping redesign of Russia’s national high school history curriculum. The previous version had drawn Putin’s ire for its openness to Western values and for the questions it raised about sensitive subjects such as Stalin’s crimes, his wartime diplomacy, and Moscow’s domination of postwar Eastern Europe.

Putin took an unusual interest in the drafting of the new texts. He chastised teachers for “utter confusion and chaos” in the teaching of history and accused educators of slanting their interpretations to meet the demands of American sources that had given money toward the modernization of Russian education.

The new history, which was implemented through a guidance document for high school teachers, focused on the end of World War II through the early years of Putin’s leadership. He demanded a narrative that was “free of internal contradictions and double interpretations.” He said the textbook project was needed to clear up the “muddle” in teachers’ minds, by which he meant critical attitudes toward Stalin’s purges, the Hitler-Stalin pact, the Iron Curtain that divided Europe after the war, and similar dark corners of Soviet and Russian history. Putin offered mild rebuke for Stalin’s reign of mass murder before delivering the main message: Stalin played an indispensable role in the creation of a modern industrial state and in defeating Hitler.

One purpose of the textbook project was to remind students that Russia had once been a great power and would be a great power again under Putin’s leadership. Where American history books take a dim view of imperialism, the new Russia curriculum brags about the country’s imperialist glory: “Stalin’s empire and the Soviet Union’s sphere of influence encompassed a territory greater than all past European and Asian powers,” it informs students, “even surpassing the empire of Genghis Khan.” And while the curriculum minimizes the role of Lenin and the old Bolsheviks (to suit Putin’s dislike for anything that smacks of “revolution”), it tells readers that communism was “an example for millions around the world of the best and fairest society.”

In introducing the new text, Putin emphasized that Russia has nothing to apologize for—not the purges; the Ukrainian terror famine; the crushing of democratic revolutions in Hungary, East Germany, and Czechoslovakia; or the absence of freedom at home. The new curriculum justifies the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact, which gave Hitler the go-ahead to wage war on Europe and carve up Poland, Finland, and the Baltic states between the two dictatorships. Other countries, Putin insisted, had even darker pages, especially America.

The new version of history also subverts the idea of an international system based on diplomacy and rules. Russia, students are told—right up to the color revolutions in post-Soviet societies—has always faced enemies who have been bent on encirclement and subversion. Under conditions of perpetual threat, Russia thus requires leaders who possess the guile and iron will of Stalin and not the weak reformism of a Gorbachev (who fares badly in the curriculum).

In the wake of the annexation of Crimea, Putin took advantage of a surge of patriotic fervor to remove academics and teachers who were resisting the new direction in history teaching. He called dissident teachers fifth columnists and “national traitors.” Meanwhile, the official version of Russian history stripped the Soviet Union’s worst crimes of their political motives. Thus the Holodomor, Stalin’s terror famine, was delinked from the leadership’s remorseless collectivization drive and desire to punish Ukraine for acts of resistance, and transformed into a tragic act of nature.

The new history meshes nicely with Putin’s hostility to liberal democracy. According to the official history texts, Stalin was prevented from introducing democratic reforms after World War II by the West’s belligerence, and not by paranoia over internal plots and a preference for the iron fist. By implication, American animosity today demands a Russian response along the lines of Putin’s autocracy. Russia, today’s younger generation is taught, always has been and always will be surrounded by enemies, and thus will always require the rule of the strongman: Putin if lucky; Stalin if not.

Rewriting Russia’s history textbooks was one part of a broader project to reshape Russians’ thinking about the past. The media also played a major role, offering up a stream of dramas and documentaries that glorified the Soviet Army’s role in World War II and justified Moscow’s control of Eastern Europe; drew attention to the plight of Russian-speakers in the Baltics; and relentlessly showcased American hostility.

At the same time, Russia is not a totalitarian state; there are alternative sources of historical interpretation available to Russians who are interested. But the available evidence is not reassuring. Opinion polls show steady improvement in Stalin’s reputation during the Putin years. Polls also show that most Russians are unfamiliar with the events of 1937, the apex of Stalin’s Great Terror, with a majority unclear about the identity of the victims or the reasons behind the show trials and executions. Likewise, a solid majority of Russians indicate support for Moscow’s postwar control of Eastern Europe. Putin’s reeducation project, it would seem, has not been in vain.

This Is How They Do It

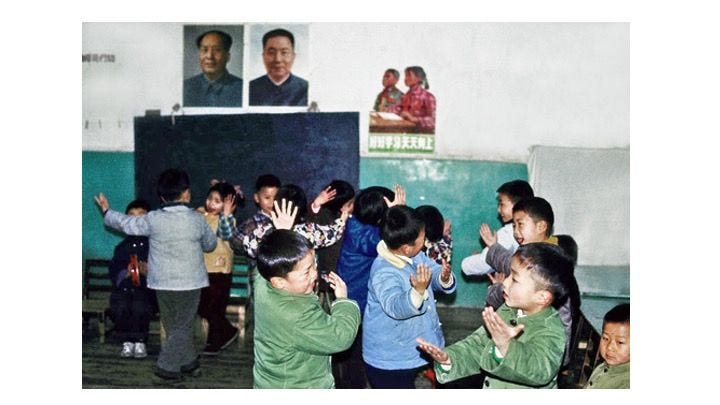

In China, as in Russia, control of the historical narrative is a state priority. Chinese leaders from Xi Jinping on down reject the idea of history as a neutral or objective exercise. History is meant to reinforce the Communist Party’s reputation and control. As such, teachers are directed to stress the achievements of China’s distant past, grievances over foreign interference, and (a scrupulously censored version of) the triumphs of the Communist Party, Mao Zedong, and Xi Jinping.

What is omitted is as important as what is included. Mao’s crimes have been erased. By any reasonable measurement, Mao ranks at the very top of the 20th century’s roster of political criminals, along with Stalin and Hitler. His malign deeds have been registered in Communist Party archives but never discussed in public. In 2016, Frank Dikötter, an authority on Mao’s rule, discovered research that estimated a death toll of forty-five million famine victims during the Great Leap Forward—Mao’s pet collectivization project—with several million executed for resisting Mao’s insane policies. Mao himself was well aware of the unfolding calamity; the party archives depict him as indifferent to his people’s suffering. Human life was of no importance when it interfered with the success of his experiments.

In addition to imposing a collective amnesia about Mao’s atrocities, the Communist Party has flatly forbidden discussion of Western values in universities, schools, or the media. In 2013 the party issued to schools and universities a directive known as the “Seven Don’t Mentions.” The unmentionables include Communist Party mistakes, but otherwise focus on the core institutions of liberal democracy. The party leadership took the challenge of stifling student discussion of Western ideas sufficiently seriously that they circulated a guidance to educators. Among its strictures: “Strengthen management of the internet, enhance guidance of opinion … give no opportunities that lawless elements can seize on.”

In countries like Russia and China, history falsification is meant to justify, obscure, or conceal mass murder, the repression of minorities, and aggression against neighbors. In Venezuela, it is designed to glorify a system, Marxian socialism, that has failed everywhere it has been attempted, and that has led Venezuela to de facto military dictatorship and economic collapse. Hugo Chávez, the late father of the Bolivarian Revolution, insisted on a curriculum that would indoctrinate socialist values in the minds of future generations while eliminating events showcasing the great moments of Venezuela’s democracy.

Notably, historic occasions like the 1958 coup against the strongman Marcos Pérez Jiménez—an event that ushered in four decades of liberal democracy, political stability, and prosperity—were scrubbed from the new textbooks. These new school textbooks, Chávez announced, would help forge a “new man” and erase “the old values of capitalism, egoism, and individualism.” The curriculum guidance reduced democracy from a system that enhances personal freedom and protects the individual from an oppressive state to a system of collective power as reflected in a powerful socialist government.

Where Chávez used history to glorify the anti-democratic left, Hungary’s Viktor Orbán has sought to delegitimize political ideas (and personalities) from the left, the center, and the right that challenge his narrow notion of national conservatism and illiberalism.

As Orbán often reminds the world, Hungary has been badly treated by history. On the losing side in World War I, Hungary was stripped of a sizable part of its prewar territory in the peace settlements. An unenthusiastic ally of Nazi Germany, it suffered a homegrown fascist movement and endured Soviet occupation and communist rule for nearly four decades. After the collapse of the Soviet empire, Hungary experienced twenty years of democratic rule, with competitive elections, the restoration of property rights, religious freedom, and a wide array of civil liberties. Like other new democracies of the post-Cold War era, Hungary’s political condition was not ideal. But by the standards of its troubled history, those two decades represented a remarkable step forward from the years of dictatorship, injustice, and war.

Since his Fidesz party swept to power in 2010, Orbán has worked nonstop to refashion the country’s political landscape, media environment, and culture. As he has consolidated control over the political system and the economy, he has steadily escalated a war on liberal, European culture—the culture that predominated during Hungary’s two decades of liberal democratic rule.

Orbán has been open about his antipathy to liberal democracy. Indeed, he and other Fidesz figures have argued that the break from the communist period did not occur in 1989, when the Soviet empire collapsed, but rather with Orbán’s 2010 election. This view casts the country’s center and center-left politicians as being substantially the same as the communists.

In a 2018 speech to Fidesz loyalists, Orbán spoke grandiosely of his election as signifying “nothing short of a mandate to create a new era.” He spoke of a “spiritual order … determined by cultural trends, collective beliefs, and social customs” and declared: “We must embed the political system in a cultural era.” Subsequently, the Fidesz government established a National Culture Council with the mandate of “setting priorities and a direction to be followed in Hungarian culture.” Orbán also issued a detailed school curriculum; among other things, it included a syllabus instructing teachers which literary works should be quoted in full and which in part.

In conducting his cultural offensive, Orbán has moved methodically to capture the institutions of learning, the arts, and the media. An intelligent and highly disciplined politician, he has gained control of most universities, the Academy of Sciences, the Petofi Museum of Literature, practically all of the country’s regional media outlets, theaters, and museums. He has also encouraged the formation of several think tanks that are dedicated to the promotion of his political ideas, the expansion of his influence beyond Hungary’s borders, and the vilification of his critics.

Among Orbán’s chief objectives has been a revisionist interpretation of key 20th-century events. He has been cagey about Hungary’s role in World War II, suggesting that Hungarians were victims just as much as Jews were victims, while downplaying the role that the Arrow Cross, the Hungarian fascist movement, played in the persecution and deportation of the country’s Jewish population. He also dredged up the reliable old anti-Semitic tropes in his campaign against George Soros, with references to “cosmopolitans” and “globalists” plotting against Hungary.

Orbán’s regime historians have concocted a wildly implausible theory of the origins of the 1956 Hungarian Revolution. According to a consensus of serious historians, the driving force behind the uprising was a coalition that included reform communists, leftist intellectuals and writers, and the Catholic Church. The principal figure was Prime Minister Imre Nagy—a disillusioned communist—who was executed after Soviet tanks crushed the revolution, and is regarded by Hungarians as a hero and martyr.

That a signal event like the revolution could be inspired by ex-communists and leftist intellectuals clashes with Orbán’s preferred interpretation of history, in which moderate liberals and social democrats are lumped in with full-blown communists on a march towards a totalitarian state. From this comes the novel theory that the revolution’s inspiration emerged from Budapest’s streets in the form of rebellious teenagers and “simple people.” Why such an emphasis? Mária Schmidt, the leading regime historian and figure behind the recasting of the revolution’s origins, has stated that Orbán’s critics are the opposite— cosmopolitans, atheists, and “anti-nation.”

In some institutions, like the media, Fidesz’ takeover has meant party control over personnel and content. In others, like the universities, the impact on intellectual freedom has yet to be felt. But in a small country like Hungary, domination over critical institutions of culture and learning by a leader with Orbán’s ambitions will likely have consequences for artists and intellectuals dependent on these entities for jobs and support. Hungarians are historically familiar with the vindictive vocabulary Orbán has injected into political life, a language of “good Hungarians” against “people with alien souls” who “promote foreign interests.” Some will resist; others, no doubt, will succumb to self-censorship.

Meanwhile, in America

There are no history wars in dictatorships like Russia and China. A single version of history prevails, stamped and sealed by the leadership and imposed in classrooms, through culture, and on the internet. In the United States, by contrast, the debate over history interpretation has been ongoing for decades. It has been waged by scholars, journalists and, increasingly and lamentably, politicians.

The current argument can be traced to the 1960s, when an intellectual school dubbed “revisionism” and inspired by opposition to the Vietnam War called into question the traditional reading of America’s role in the world. Revisionists were skeptical of claims that American policy was motivated by an impulse to spread freedom; they generally treated America as a destructive force, inclined by militarism, racism, imperialism, and greed.

Often influenced by Marxist categories, the revisionists were especially focused on the origins of the Cold War; they brushed aside the traditional view that the conflict’s source could be found in the Soviet Union’s totalitarian and expansionist system and Stalin’s paranoia. Some revisionists drew on their conclusions about the unsavory nature of U.S. foreign policy to make the broader case that America itself was anchored in inequality, prejudice, and exploitation. Revisionist scholars were unhindered in arguing their case; protected by tenure; and often praised by critics. But while revisionist academics left an imprint on scholarly judgments of U.S. global behavior, revisionism itself was largely rejected in the wake of the Cold War’s peaceful conclusion, the repudiation of Marxism, and the embrace of democracy by much of the world.

The debate over revisionism was intense and polemical, but it was largely conducted by scholars and journalists and much less by elected officials. Indeed, the United States has been unique in the limited role that the national government plays in the determination of what the schools will and will not teach. Curriculum decisions are highly decentralized, with textbooks selected by authorities in each of the fifty states, and often by municipal school officials. The selection of an American history syllabus is messy and open to pressure tactics from organized and sometimes well-funded lobbies representing diverse ideologies, identity groups, and religious denominations. Today, there is a legitimate complaint that history and civics have been shunted to second-class status throughout the education system, and that students leave school functionally illiterate about America and the world.

The upsurge in political polarization has made the process of forging a national consensus around an American narrative practically impossible. American history has expanded into a much broader undertaking than a debate over high school textbooks. America is notable for its academics, journalists, biographers, memoirists, and documentary filmmakers, all of whom contribute to the shaping of the American story. America’s intellectual pluralism, the stellar quality of its historical writing, and its constitutional protections for freedom of speech and inquiry render the idea of history via presidential decree à la Vladimir Putin inconceivable. Yet there is a dark side to that magical word “diversity” in the competing versions of the American story that have emerged in recent years. The competing versions have become competing demands for the adoption of one or another explanation of the American story.

The divided climate within which this debate rages presents America with a serious dilemma. Daniel Chirot has written that “not having a unifying history can permanently cripple a nation’s ability to cope with major crises.” America was well served for decades by a story that spoke of a society that was open to change, expanded individual rights, protected minorities, and that was committed to the rule of law—an optimistic story that stressed the ability to adapt and expand personal rights even while acknowledging deficits and systemic failures, with racial inequality front and center. Does the United States today have such a unifying story? To answer this question, we must also answer whether those who are demanding a top-to-bottom reassessment of the American story are seeking one unifying history, or whether they can accept a plurality of versions, including ones in which America is depicted as a failed experiment.

From the American left and right, we hear arguments that are hostile to the liberal values that lie at the foundation of American democracy and American history. From the right, critics have recently come to describe the American system as deeply flawed, with claims that liberalism today bends toward the authoritarian. An extreme version identifies liberalism in America and elsewhere as a new variant of totalitarianism that imposes ideological conformity and imposes rigid speech codes. The equation of liberal democracy with totalist creeds like fascism and communism has yet to achieve widespread credibility. But the concept is growing, and is drawing inspiration from such enemies of democracy as Putin and especially Orbán, who has been recognized as a kind of conservative guru by many American conservatives.

On the left, there is a growing insistence on an interpretation that places racism and white supremacy at the center of things. Like the Right, elements of the Left have developed a post-Enlightenment critique that is skeptical of liberal values and rejects optimistic tellings of the American story. This is explicit in Critical Race Theory (CRT)—a system of analysis that judges institutions through the prism of racial inequality—and is implied in the broader works of anti-racist theorists like Ibram X. Kendi. CRT has gained a stature on campus that Marxist theory once enjoyed. Like Marxism, anti-racist criticism fortifies a student with an ideology that has an explanation for practically every political or cultural phenomenon.

Scholars who judge politics through racialized categories are dismissive of what they characterize as “liberal myths” such as color blindness, free speech, meritocracy, and equal rights under the law. Kendi (a recent recipient of a MacArthur Foundation “genius grant”), has proposed a constitutional amendment that would establish a Department of Antiracism with the authority to pre-clear all federal, state, and local policies for racist impact. As to what constitutes racism, Kendi asserts that any evidence of racial inequity is evidence of racist policy. But by broadening the class of victimized minorities to embrace all “people of color,” leftist critics are indirectly damning one of the most successful liberal bulwarks: the American immigration system.

The Right has taken CRT and transformed it into a subversive bugbear much like Joseph McCarthy did with communism. Ironically, Republican legislators, in piecing together state laws to forbid the teaching of CRT, have appropriated language from fearful leftist undergraduates who speak of trigger warnings and safe spaces, referring to “discomfort, guilt, anguish, or any other forms of psychological distress on account of the individual’s race or sex.”

The growing disillusionment with liberalism is welcome news for America’s adversaries. Modern authoritarians fear American-style democracy; understand the subversive power of liberal ideas; and are going to extraordinary lengths to destroy nascent democratic institutions and to suppress discussion of concepts like individual rights, civil liberties, and freedom of expression. There are no honest discussions in China or Russia about police abuse, defendants’ rights, the persecution of minorities, or the rights of believers who resist state control. Xi Jinping’s “Seven Don’t Mentions” stands as a foundational document in thought control. It’s worth taking careful note of the forbidden subjects it singles out: universal values, civil society, civic freedom, an independent judiciary, and press freedom. These are the building blocks of democracy, the very institutions that impressed Tocqueville during his American tour. More recently, they inspired millions during the final decades of the 20th century, and they continue to inspire people in dictatorships like Belarus and in countries like Taiwan and Ukraine that are menaced by neighboring dictatorships.

If there is to be a “reckoning” over American history, we should keep in mind that the consequences will be felt beyond our borders by the many millions who continue to find inspiration in the American idea.

Arch Puddington has written widely on democracy and its adversaries. He is author of the Freedom House Special Report, Breaking Down Democracy: The Goals, Strategies, and Methods of Modern Authoritarians (2017).

Image: Public domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=96071656