How Social Media Destroys the Things That Matter Most

We need freedom and structure. Digital platforms are eroding both.

From time to time, we take deep dives into topics that run longer than our average piece. In today’s longer read, the FIRE’s Talia Barnes and Persuasion editor Luke Hallam explore how social media undermines our attempts to find balance between freedom and structure.

— The Editors

A two-sided coin

Over the past 10 years, rates of social media use have climbed alongside depression and anxiety, political polarization, institutional distrust, and an array of additional worrying trends. As social psychologist Jonathan Haidt noted in his aptly titled Atlantic article, “Why the Past 10 Years of American Life Have Been Uniquely Stupid,” something has felt off in recent years, America seems to have had a worse time of it than other places, and anyone can see that social media plays at least some role in what’s happening.

Though many who use these apps or see their real-world ramifications recognize the sense of malaise that hangs over much of our interactions and experiences, it’s difficult to pinpoint the precise origin or nature of this cloud of problems. Attempts to do so often yield two seemingly contradictory throughlines.

The first emphasizes that the freedom enjoyed by older generations is not available to young people today. This view is supported by studies showing increased self-censorship, attacks on freedom of speech, and the rise of helicopter parents who limit childhood autonomy.

The second emphasizes the apparent lack of structure in our lives, evidenced by the loss of confidence in shared institutions, a decline in community engagement, and the fact that local organizations are losing their sway to generic megacorporations. The claim here is that the shared narratives that once bound people together have lost much of their power.

Both accounts identify social media as one of many driving forces behind what’s gone wrong.

Paradoxically, they’re both correct: Our culture is characterized, simultaneously, by a lack of true freedom and a lack of meaningful structure, and both problems are exacerbated by the nature of our online “communication” platforms.

To understand how this can be so, we must recognize that “freedom” and “structure,” though apparent opposites, represent flip sides of a single coin—both equally vital for a functioning society. Author and psychologist Dr. Peter Gray’s summary of Basic Psychological Needs Theory describes the relationship between these two values: “To feel in charge of your own life you must feel free to choose your own paths … feel that you are sufficiently skilled to pursue those paths … and, as a social being, have supportive friends and colleagues who care about you and give you strength to pursue your paths.”

In other words, freedom has value because it allows us to find structure, while structure has value because it helps us to exercise freedom. Only through a healthy relationship with both do we feel empowered and connected.

On the other hand, when freedom is stifled or misdirected, people feel anxious and trapped; and when structure is thwarted or tampered with, people feel depressed and disoriented. This suggests why social media is contributing to a sense that everything is going wrong. When it comes to both freedom and structure—those precarious interrelated values—digital platforms offer us the hope of something meaningful, and spectacularly fail to deliver.

False freedom

Social media warps autonomy by selling us the idea of freedom, while providing none of the conditions that incentivize authentic self-expression.

First, the sell. Those who approach social media sites believing that they offer a space to discover and be our authentic selves don’t arrive at this impression in a vacuum. They are simply internalizing the core message put forth by the companies themselves. Instagram’s 2021 brand campaign, “Yours to Make,” perfectly encapsulates the hopeful ideal of autonomy represented by social media:

For young people, identity isn’t defined, it’s something that’s constantly explored. Whether that means connecting more deeply with the people that matter to you, discovering and experimenting with new interests, or sharing your perspective, however work in progress it may be … Instagram believes when we have a place to collectively explore who we can be, we move ourselves, our communities, and even the world forward. It’s Yours to Make.

Indeed, experience may feel like “ours to make” when we’re posting in our pajamas from our bedroom, comfortable and physically alone. But once that post is live, it takes on a life of its own. Our painful awareness that we are not, in fact, alone—and our capacity to feel shame when exposed to the judgment of others—inextricably shapes our actions and expression online.

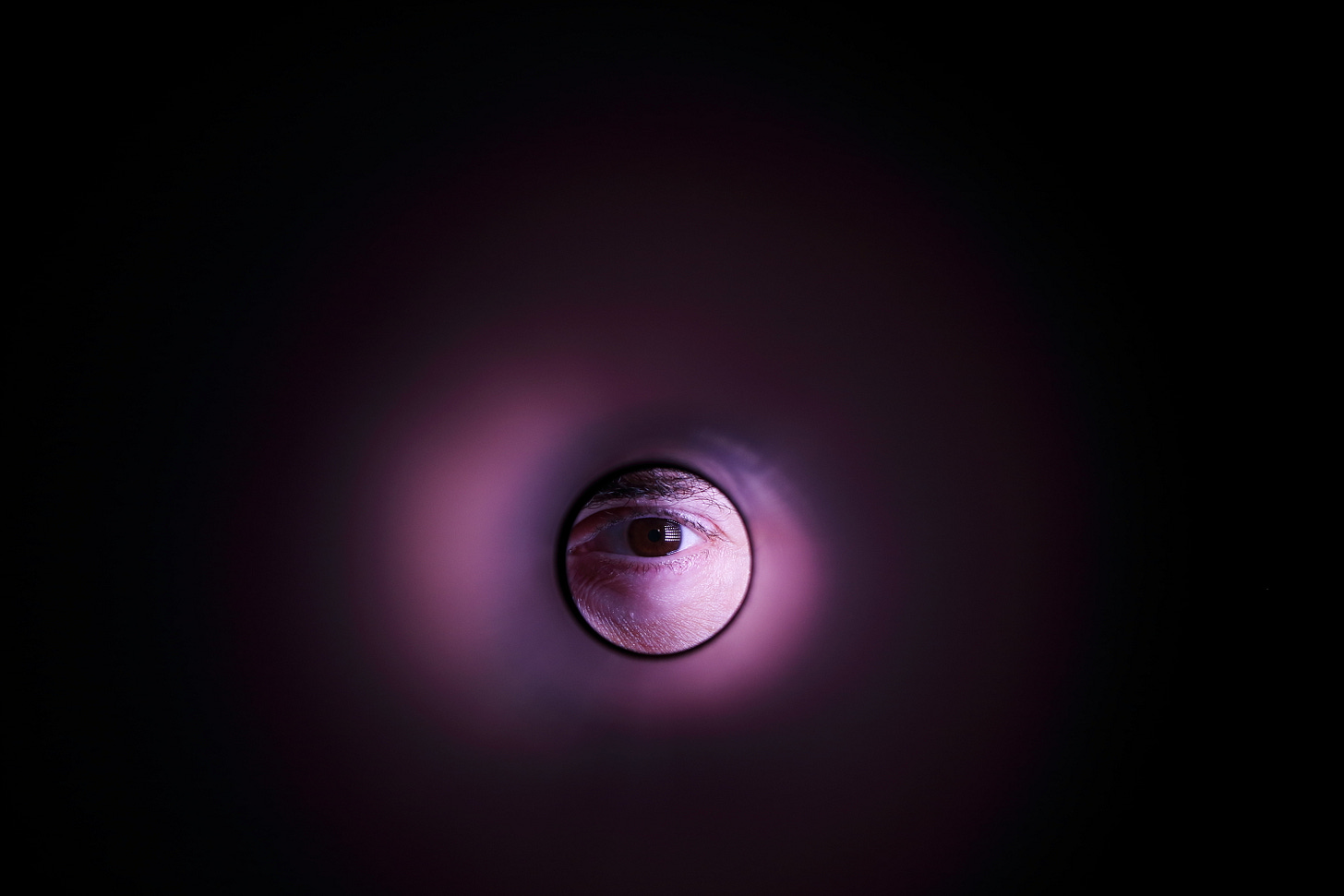

There is an insightful passage on shame in the French philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre’s 1943 book “Being and Nothingness,” in which Sartre asks the reader to imagine someone peeping through a keyhole, trying to see into a locked room. Sartre describes how the gazer hears footsteps behind her: She is being watched. Instantly, she recoils from the keyhole. In Sartre’s estimate, the gazer, initially immersed in the experience of the other room—in a state of free-floating consciousness—becomes self-conscious, regretful, and alert to herself and her thoughts because she knows she is being watched.

“It is shame … which reveals to me the Other’s look and myself at the end of that look,” writes Sartre. Upon sensing the presence of the Other, the gazer intuitively sees herself through the newcomer’s eyes, becoming self-conscious, aware of herself as a kind of object. Shame, for Sartre, is “the recognition of the fact that [one is] indeed that object which the Other is looking at and judging.”

For those of us who spend a significant amount of time on social media, this disorienting dance of engaging and recoiling—fueled by an alternating sense of autonomy and shame—will sound familiar. It happens every time we check our phone. By cropping, coiffing, and curating the persona we display, signaling allegiance to popular causes, and publicly casting judgment on others who transgress unspoken social rules, we objectify ourselves with others’ judgment in mind. LinkedIn perhaps embodies the logical endpoint of this process: in theory, a site for making business connections; in reality, a space where people post little more than “on message” platitudes under the guise of celebrating identity and individuality.

Of course, curating your online presence is not alarming in and of itself. We are social creatures after all, and picking up on social cues can help us forge relationships and avoid conflict. We should, however, be concerned when our efforts to fit in come at the cost of our sense of self.

When we’re confronted with a near-endless array of signs, memes, and fads with which to construct an “identity,” it’s no surprise when our own inner voice gets drowned out. Sartre would say that on Twitter and Facebook we are forever turning ourselves into an “object” to be judged, thereby participating in an endless cycle of self-curation and shaming, all while being told that our unique identity is the most important thing about us and that it’s “ours to make.”

We are forever peeping through the keyhole—we cannot help ourselves. At the same time, we are forever adjusting ourselves to the condition of being seen—with all the pathologies that entails.

False structure

One might think that an online culture hostile to meaningful freedom would necessarily be characterized by strong structures, groups that function as communities. But this is laughably (cryably?) far from the truth. Just as social media promises—then undermines—autonomy, it also tantalizes us with the prospect of community, only to snatch it away before we can enjoy its benefits. To understand how, we should first ask: What is community?

The word itself, like many of its real-world manifestations, suffers from a crisis of meaning. The Oxford English Dictionary describes “community,” simply, as “a group of people living in the same place or having a particular characteristic in common.” By this definition, algorithms that guide user engagement on social media do an excellent job of fostering community, identifying people with shared interests, and grouping them together via similarly curated content feeds. Advertisers are all too happy to run with this definition—think, “the Facebook community”—capitalizing on the warm fuzzy feeling associated with the word while contending with none of the meaning that evokes that feeling.

Fabian Pfortmüller, co-founder of the Together Institute, gives the word some much-needed texture in a thought-provoking Medium article. True community hinges on more than common interest, he says. “I have so, so many attitudes, interests and goals that I share with other people. But that doesn’t mean yet that I’ll feel a sense of community with them.” Nor does it hinge on shared goals. The key ingredient of “community,” according to Pfortmüller, is relationships. And relationships are built on trust.

But how can we trust people whose lives and personalities are predominantly known to us through a series of filters? How can we reap the rewards of the difficult parts of relationships—the harsh-but-necessary criticism, the brutally honest advice, the confrontation, the intervention—without first believing that the person delivering the message truly knows, cares about, and ultimately accepts us? When “communities” are mediated by algorithms rather than chosen in a meaningful way, we lose control of the terms of our membership in (or ostracism from) them. Can these interactions really be considered “relationships” in anything but the most shallow sense of the word?

Put simply, communities are personal, while the algorithmic sorting mechanisms intended to create them on social media are deeply impersonal, funneling users into echo chambers of people who may superficially share the same perspectives but are irretrievably distant, unequipped to engage with one another’s full humanity the way a close relative or friend could.

In this way, social media perpetuates a funhouse-mirror version of community: the stifling conformity, the threat of being cast out. Simultaneously, it disincentivizes the actual thing: the healthy feedback and critique, the sense of belonging and acceptance. Endless sorting (especially insidious when it has the impression of being self-directed) disconnects rather than connects individuals, unravels rather than facilitates social ties, and shrinks users’ worlds to only that content which generates their immediate engagement.

The mental health data speaks for itself. A 2017 study shows that young adults who heavily use social media—50 or more visits per week—have “three times the odds of perceived social isolation as those who went online less than nine times a week.” Ironically, the end-result of hyper-personalization may be a reality characterized by the opposite of belonging: billions of “communities” of one.

Who thrives in dystopia?

The British anthropologist Robin Dunbar argued that a single person cannot really maintain more than 150 social connections at once. Throughout most of history, humans have existed within this limit, amassing social groups consisting of a known quantity of friends, family, colleagues, and acquaintances. The key word here is “known.” Our relationship with these others would have been characterized by mutual trust built over the course of a sustained effort to get to know one another. Under these circumstances, individuality is not easily thought of as threat; criticism, not so easily associated with attack.

Today, on the other hand, the size of our network of interactions is unprecedented and fluctuates wildly with the popularity of each post we share. Interpersonal trust, the glue that keeps relationships healthy and productive, is stretched too thin on social media. Pressure to hold this unnatural position incentivizes two disparate, yet mutually reinforcing, patterns of behavior.

The first is conformity: sacrificing one’s autonomy to the perceived will of the group. Those who most fully embody this ethos may avoid saying publicly any thoughts that aren’t considered absolutely acceptable among their in-group—to appropriate a phrase from George Orwell, they wear a mask, and their faces grow to fit it. With any sharp edges sanded down, they may begin to sound more like brands than human beings, and conflate merely posting with participating in “the conversation.” In reality, this mode of interaction contributes to the warping effect of social media, making group consensus appear more monolithic than it really is and deadening the discourse.

In such a stale environment, few are willing to break the mold, and those who are tend to do so abrasively, exploiting the opportunity to generate attention. Thus, the second pattern of behavior: selfishness, or abandoning an ethos of community altogether. Those who reflect this archetype gleefully embrace their worst impulses, substituting trollish taunts and personal attacks for ideas and programs to gain power or status—perhaps amassing large followings in the process.

Of course, no individual engages with others in only one way. As the conformist’s meekness sets the stage for the bully and the bully’s ire incentivizes conformity, we are called, opportunistically, to be one, the other, or both. “If we demand that our public figures tolerate the occasional insane hellish mobbing (or even tolerate the risk of facing it),” notes the writer Sarah Haider, “we are filtering for pathological personalities to fill our public discourse.” She’s right. It’s hard to escape the feeling that the warped incentives of social media facilitate an ever-intensifying feedback loop of antisocial, anti-relational behavior.

There must be a better way.

Touching grass

Social media isn’t real life, but it undeniably influences it. Those who design these sites should strive to implement systems that enable people to exercise the best version of freedom and find the best version of structure. Increased transparency regarding content filtration and the murky workings of algorithms, or adjustments to “like” and “share” functionality, represent pieces that can help people relate to one another more organically, leaving them feeling less fragmented and more whole.

But picking up the remaining pieces will be left to individuals, and must entail engaging outside of the constricting and warping structures of these apps altogether: in other words, touching grass, as the internet idiom goes. Along these lines, where autonomy is broken, we might seek out physical and psychological spaces conducive to self-understanding and expression: This might be as simple as taking long solitary walks or spending time on artistic pursuits. Where community is broken, we might foster belonging: becoming involved with local civic institutions, maintaining close friendships, or getting to know our neighbors.

What common thread binds efforts of this kind? A shared recognition of human complexity.

More than a two-sided coin, autonomy and community are like a yin-yang symbol: healthy independence requires some outside input; healthy group belonging, some individual agency. To live well means reckoning and wrestling with this apparent contradiction, rather than selling our souls, wholesale, to social media’s warped idea of one or the other.

Talia Barnes is a writer and copy editor for the Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression (FIRE).

Luke Hallam is an associate editor at Persuasion.

You might also like:

Jonathan Haidt and Yascha Mounk discuss why public discourse has become so toxic on the Good Fight podcast.

Beatrice Frum on “shadow banning,” the perils of social media, and her choice to leave TikTok.

Follow Persuasion on Twitter, LinkedIn, and YouTube to keep up with our latest articles, podcasts, and events, as well as updates from excellent writers across our network.

I love Haidt since reading "A Righteous Mind"; however, although I do agree with much of his blaming of social media for wrecking so much of western society, I think he misses the actual root cause that Jordan Peterson nails.

It is our western education system. It is a hive controlled by the human species of radical malcontents. It is the seed of social, political and economic dysfunction that social media only serves to amplify. And the rot of the toxic ideology of critical theory is front and center for pushing the dysfunction into the system and thus into society as the little graduated darlings are thus programmed to rage at all the things they yet possess the wisdom to understand.

Haidt blaming social media is like blaming the misfiring of the sprinklers for the weeds taking over the garden.

And it isn't social media per se that is the sprinkler problem; it is the filtering algorithms. Social media does good as it was originally designed to network people together. It's original vision was to enhance human connections and conversations; thus increasing understanding of diverse thought, views and opinions. But the algorithms do just the opposite. The put people in group-think bubbles where their myopic bias is strengthened by a information feed tailored to make them feel smugly right about everything. Then in the rare case of an opposing view getting based the gate-keeping robots, they explode with rage claiming the source to be a science denier, a threat to democracy, a radical white supremacist fascist... and they support a Biden Administration Ministry of Truth to shut down those terrible people that are obviously dangerous in their wrongness.

My perspective in all this is that the current education system along with the algorithms are the real threat to democracy. They are both out of compliance with American First Amendment rights as they actually take over to direct thought and speech. They also break the Forth Amendment in the guaranteed rights of privacy... because they document our opinions and use information and use it to make us targets.

Remove the fake scholarship toxic ideological programing of Critical Theory from the education system, support education choice to allow parents to get their kids out of the Marxist hive. Then implement new legislation that limits the use of algorithms to filter content to feeds and replaces it with users' choice and acceptance for how their feeds are configured.

An admiral effort at dissecting a complex problem. I wonder if the following is a possibility: a new social media platform whose algorithms are heavily informed by humane values. Uncivil and unhealthy behavior in various forms would be blocked. Freedom and self-expression would take a back seat here, not to conformity, but to simple decency. Why not? Why should tech nerds, corporate profiteers and the pathological rule this medium? Tweaks to the existing formats suggested by the authors and J. Haidt would help. But what we ultimately need is a regenerate culture with its own institutions.