In a World Obsessed With Innovation, What If Most of It Isn’t Real?

Bullshit jobs aren’t just a phenomenon of bureaucracy. They’re in tech, too.

In the beginning was the work. The work was done. The work was real. Then, somewhere along the way, work became just motion.

It was like virtue signaling—only worse. At work, I practiced another kind of signaling: innovation signaling. Everyone knows innovation is the ultimate corporate virtue. For years, it wasn’t innovation itself but the signaling of it that I performed. Innovation signaling was my job.

And not just mine.

At Mastercard, I made around $250,000 a year. Over six years, my title changed—Enterprise Architect, Director of Strategy, Principal of Technology. When you’re an engineer, “Principal” is the ceiling if you’re not interested in managing people, and I hit it early. With nowhere to go upward, I moved sideways instead—new bosses, flights to Manila, Dubai, London, and headquarters in New York.

There was movement—through airports, through inboxes. Emails received, emails sent. We gathered in front of whiteboards, drawing the shapes we learned in kindergarten: squares, circles, triangles, arrows connecting them. Each stood for something—systems, messages, networks, the physical, logical, or business layers of whatever new innovation we were trying to invent. When it became too obvious that it wasn’t new, we said we were reinventing. When even that felt untrue, we called it reframing, repurposing, reusing.

What we produced was usually an abstraction of what already existed, wrapped in something new—sometimes just new buzzwords. Because you have to move—even when you’re not inventing anything. You have to check the box, upload the file to an internal shared-drive graveyard—a proof of motion, a justification to others and to ourselves that work had been done. That the high salary reflected merit. That it was earned. That it didn’t come at the cost of something else.

I don’t know when I started noticing that all the movement was the same kind of nothing. Maybe it had started disappearing even earlier, and I just hadn’t seen it—because I was anchored to a different time, blinded by my own expectations of what work was supposed to be. Maybe I was still learning, and I mistook learning for doing. There was a lag in perception. I’m just not sure what caused it.

It’s not a great revelation—David Graeber wrote Bullshit Jobs back in 2018. But we were technologists. Bullshit jobs were for administrators and bureaucrats, for consultants and life coaches, for people selling insurance or purpose. Not for us.

At first I thought it was just a short-term lull. Maybe my team was signaling innovation this year, but other teams might do something real. Or if not them, then surely the company. But there was nothing.

I moved everywhere, touched projects, asked people: “So what are you working on?” Every conversation followed the same arc: “What? Then what? So what?”

Sometimes work looped back on itself like a recursive function. Sometimes it was a dead-end street. Worst of all—a highway that ends midair.

It never added up to anything.

I started checking the company’s press releases. Everything sounded groundbreaking. Blockchain! Cutting-edge innovation!

But it wasn’t. I knew what those projects actually delivered because I was leading some of them. When I came across a press release I wasn’t sure about, I started feeding them through AI.

Copy.

“Is this true innovation or innovation signaling?”

Paste.

One by one, every single one of them came back as innovation signaling. Every. Single. One.

The job of almost everyone I worked with at Mastercard for six years was the same as that of the marketing team writing press releases. We were all spinning, packaging, messaging. The only difference was our audience. I took the spin upward—to my boss and senior leadership. That I was worth keeping. That I was worth $250,000, plus benefits, equity, and remote work. The marketing team took it outward—to the public, to shareholders. To you.

It’s not so obvious. You see logo changes, a new chime when you check out, a slick Super Bowl ad, your card made to look like titanium. But what’s behind all that is old. Mastercard’s “switch”—the company’s bread and butter, the monolithic system that authorizes, clears, and settles transactions—was built during the Nixon era. It’s still the same.

But there is always something that can be pushed out as transformative, digital-first, next-generation, seamless, future-ready, AI-powered, priceless. But it was the same thing as before—just repackaged, rebranded, abstracted. You thought it was new. We pretended it was new.

Later, I moved on from Mastercard and joined consulting companies. More travel. I touched more companies. Banking, financial services, fintech, consulting—saturated with people signaling innovation.

Financial gatekeepers: Experian, TransUnion, Equifax, FIS, Fiserv, PayPal, Stripe. They don’t innovate; they extract.

Internet and cloud infrastructure: Equinix, Digital Realty, Cloudflare, Akamai. They own the digital roads and charge tolls.

Logistics monopolies: UPS, FedEx, Union Pacific, BNSF. Generating private profits on public dependence.

Healthcare and identity gatekeeping: Epic Systems, Cerner, UnitedHealth, ID.me, LexisNexis. They control access to health and identity, but not for the public good.

Capitalism shouldn’t tolerate this kind of work across so many corporations for long. There’s competition, there’s supposed to be rational choice. Customers vote with their feet. Stop innovating, and they should go elsewhere.

But these companies do not just last. They thrive even though they don’t innovate. Because of the digital machinery they inherited. Because of network effects, barriers to entry, locked-in customers, hostile acquisitions.

The companies I worked for made plenty of money. No matter what happened—COVID, mass layoffs, war in Ukraine, any global crisis—someone would always say: “Well, our cash coffers look good.”

We could weather any storm—stagnation, stagflation, shrinkflation, inflation, hyperinflation, recession. You name it.

Bonuses. Promotions. Record profits. The company’s coffers stay full.

These companies don’t just survive. They thrive.

Economist Tyler Cowen has asked: What happens when two-thirds of the economy is stagnant?

I think what he identified on the macro scale, I experienced on the micro level. How much of the white collar economy is actually fake?

I think I was trapped in the stagnant two-thirds. Then again, maybe “trap” isn’t the right word. I was making $250,000 a year. Some might call that floating.

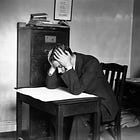

For some reason, I keep thinking of that drifting, aimless plastic bag in American Beauty. So free—yet still just a plastic bag. Floating. Polluting. Empty.

Sarah Majdov is a computer engineer and technologist who spent years in what she calls the “Goldilocks position” of corporate life—right in the middle, high enough to glimpse strategy, low enough to understand execution. She is the author of Fatamorgana.

Follow Persuasion on Twitter, LinkedIn, and YouTube to keep up with our latest articles, podcasts, and events, as well as updates from excellent writers across our network.

And, to receive pieces like this in your inbox and support our work, subscribe below:

“Over six years, my title changed—Enterprise Architect, Director of Strategy, Principal of Technology.” This is a wonderful essay. For a couple of months recently, I watched a group of men build a house next to where I was staying. They were skilled and produced something both useful and enduring. I asked myself how it came to be that we valued bullshit jobs with bullshit titles more than what I saw these men do.

I lasted about six years at a Fortune 500 company. For years I had a recurring nightmare that I was back there and would wake up in a state of panic. The only good thing about the nightmares was that I was still young and skinny. My former coworkers still believe the empty slogans. Thoreau had it right, “the mass of men (and now women) lead lives of quiet desperation.”

This is everywhere. I worked for a local government and my reviews were centered around process improvements and extra curricular activity. As a PM you’d think excellent project management would be a priority. No. As long as the projects were not going badly then the focus shifted to virtue signaling in other ways. I pulled back on extra curricular activities and my boss said I wasn’t “engaged”. What? I was spending more time doing my job.