My friend Steve Rhoads, emeritus professor at the University of Virginia, will be publishing through Cambridge University Press a 35th anniversary edition of his 1984 book The Economist's View of the World. The book reviews and explains many of the fundamental concepts of modern neo-classical economics, like opportunity costs, marginalism, incentives, externalities, welfare, consumer preference, and the like in an informative and balanced way. This lays the ground for the book’s final sections that contain a trenchant critique of economic thinking, questioning many of the assumptions that underlie it like stable preferences, neutrality with regard to higher and lower tastes, individual selfishness, and the political sovereignty of consumer choice.

When I first read the book back in the 1980s, I thought it was a devastating critique of the blinkered perspective of the discipline. But it’s a measure of how far my own thinking has shifted that my reaction on reading the revised edition was that it was a bit too supportive of many traditional economic ideas, despite the many revisions contained in the new volume.

___STEADY_PAYWALL___

Let me focus on just one issue for now, which will be a big one for the Biden administration. That is industrial policy, that is, government support for specific sectors of the economy in an effort to goose economic growth. The Economist’s View of the World repeats many of the standard objections to industrial policy that were made thirty years ago. Government bureaucrats are not very good at picking technologies of the future; they have no skin in the game and therefore face distorted incentives and risks; and most importantly, they are likely to use their powers to satisfy political rather than economic objectives. The book points to many of the real-world failures of industrial policy, like the Carter administration’s support for synfuels or the Obama administration's subsidized loans to Solyndra.

And yet, industrial policy has been used successfully by many countries including the United States, in ways that economists fail to acknowledge. East Asian fast developers like Japan, South Korea, Taiwan, and China used different versions of industrial policy to produce historically unprecedented rates of economic growth. There has been a long failure of American economists to recognize this record. The World Bank’s 1993 World Development Report, The East Asian Miracle, tried to pretend that Asia’s success was due to their having followed orthodox neoclassical prescriptions like stable money and fiscal discipline. The Japanese, who happened to be paying for that year’s report, were upset by these conclusions since they knew that they have made use of all sorts of heterodox techniques like directed credits to speed up technological development. The Bank was forced to revise the study, but did so very grudgingly and to this day has not really been willing to admit that industrial policy could be used to good effect.

There are a lot of caveats to this conclusion, coming out of the large literature on "developmental states." Industrial policy will work best for a late developer who is following a path blazed by earlier powers; as it reaches the technological frontier, governments do indeed become less able to predict the future relative to markets. This is why industrial policy has faded as a policy tool for Japan and South Korea in recent years. Moreover, successful industrial policy, as Stephan Haggard has shown, depends on certain political conditions, namely, a high-capacity bureaucracy that is adequately shielded from overt political pressures, something that Peter Evans labeled “embedded autonomy.”

But it is not just governments in East Asia that have managed this successfully: the United States has had an industrial policy for many years, only it is not labeled as such. Rather, it is called the Defense Department, where cutting-edge technology investments have been made by the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA). Many of the foundational technologies of our era, including computers, radar, semiconductors, integrated circuits, and, most famously, the internet all started out as government-funded military projects. When DoD starts spending money big time on a project like the F-35, politicization kicks in and the manufacturing is spread out over as many congressional districts as possible. But the government has proven able to act like a venture capitalist when technologies are new and the stakes not quite so high. As with the Asian fast developers, the trick was that DARPA was run by technocrats and managed to stay out of the cross-hairs of politicians seeking to grab hold of its budget and agenda.

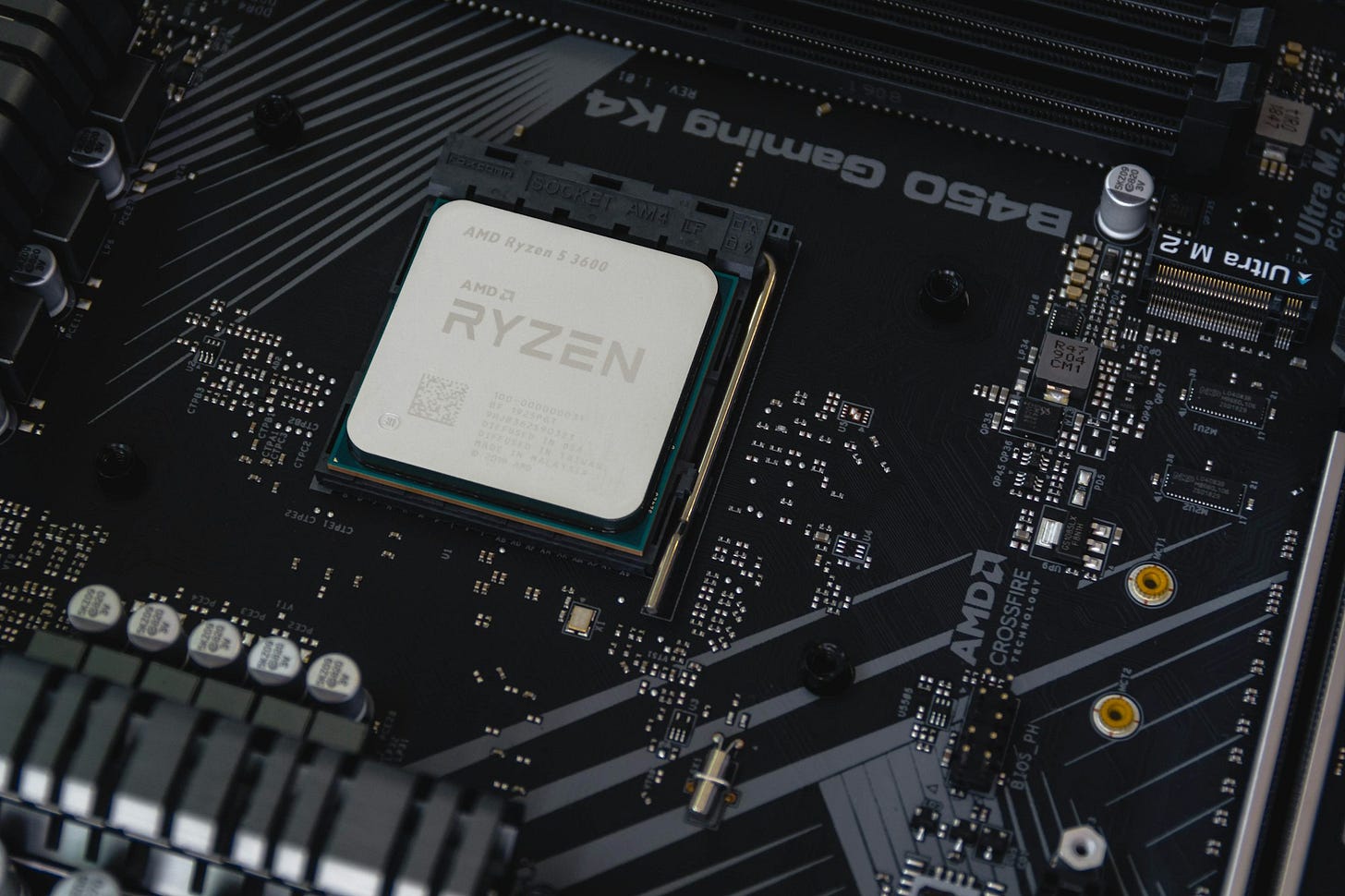

The Biden Administration is pushing industrial policy in two areas, both of which are fully justified in my opinion. The first concerns the review of hi-tech supply chains mandated by an executive order in February, that would look at sourcing of semiconductors, pharmaceuticals, rare earths, large capacity batteries, and the like. This has been triggered by the global shortages in semiconductors and medical equipment induced by the Covid pandemic.

The U.S. and other Western countries remain critically dependent on China and Taiwan. A single Taiwanese company, the Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (TSMC), accounts for 50 percent of global supply. Veteran American companies like Intel had turned to outsourcing their manufacturing abroad until consciousness of the strategic vulnerabilities this created forced an about-face this year. China has announced that it intends to re-incorporate Taiwan within the next few years, and if that happens, it will come to dominate global supply.

The threat to supply chains for everything from automobiles to game consoles is part of a much larger problem of hi-tech competition. At the moment, the Chinese company Huawei is the dominant supplier of 5G telecommunications equipment.

Its only real rival is the Swedish firm Eriksson, whose products are more expensive if more secure. While Chinese dominance in production of, say, plastic toys was probably inevitable, there is absolutely no good reason why this was an inevitable outcome in hi-tech products like telecom switching equipment. The U.S. used to be a major supplier in this sector when Lucent Technologies was spun off from AT&T in 1996 after the latter’s breakup. But the economists who controlled the conversation in those years were only interested in efficiency. Lucent merged with France’s Alcatel SA, which was then absorbed by the Finnish firm Nokia. There were other more profitable sectors for the firm’s owners to engage in like mobile handsets, and in any event the massive supply chains and accompanying knowledge that make manufacturing possible had already moved to Asia.

And so the manufacturing capacity simply leached away without anyone paying attention. It didn’t occur to anyone back then that physical location would make a difference if the world re-polarized geopolitically. The same can be said for hi-tech magnets and the rare earths that are needed to produce them, as indicated in this recent Wall Street Journal article. So today, an industrial policy to reduce dependence on China in these sectors is absolutely called for.

The second area in which the Biden Administration is considering industrial policy is in its effort to speed transition to a low-carbon economy. In my view, the U.S. is currently in a position similar to Japan in the 1950s or Korea in the 1960s: there is a path of technological transition that is fairly easy to foresee. While hydrogen may be the fuel of the future, that horizon is pretty distant at the moment. We are already well on our way to an electrical-everything future powered by alternatives and batteries, and industrial policy can help speed that process. The infrastructure plan announced by the Biden Administration contains money for subsidizing electrical charging stations across the country, a lack of which is currently one of the main deterrents to the more rapid consumer uptake of electric vehicles.

There is always risk of politicization when the government decides to spend large amounts of money on anything. How we have avoided that in the past and how we could avoid it in the future if a big infrastructure initiative actually materializes will be the topic of my next post.