Is the Climate Crisis Just Too Hot for Us to Handle?

Probably not—if we give citizens a way to talk to each other without the polarizing labels.

As world leaders meet at the Glasgow Summit (COP26) to confront the climate change crisis, many question whether American democracy can muster the political will to act effectively. Can the United States—the second biggest contributor to greenhouse gas emissions after China—adopt the kinds of dramatic, long-term changes necessary to reach net zero, the point at which we stop adding to the total of climate-warming greenhouse gases in the atmosphere?

As freedom recedes and authoritarian power surges, whether the United States can help lead a global transition to net zero has become an existential challenge not only environmentally but politically. Our democracy is being tested in two respects. First, can we rise above our crippling levels of political polarization to adopt the far-reaching, long-term policy solutions that will be needed? Second, can the public comprehend such a complex subject? Is it possible to engage the American people in thoughtful debate on a range of possible solutions that would greatly affect their daily lives? It is difficult to imagine a change in America’s energy profile of the scope arguably needed unless the American people can be engaged and significant bipartisan agreement forged.

From our most recent deliberative poll, which brought together a representative sample of 962 Americans in September to deliberate online in video-based discussions, hopeful answers to these questions emerged. America in One Room: Climate and Energy, a collaborative project between the non-partisan problem-solving organization Helena and Stanford University’s Center for Deliberative Democracy, was the largest national experiment with in-depth deliberation ever conducted. It sheds light on what the American people would think about climate change and the policy alternatives to address it if they could weigh the issues with one another under “good conditions” of mutual respect and accurate, balanced information.

Each participant received a set of balanced briefing materials including pro and con arguments for each policy option. They discussed the policy options online in diverse small groups and then, in online plenary sessions, questioned experts with differing points of view. They were polled on their views before exposure to the briefing materials and deliberations and again at the end of the process. This gave us an opportunity to measure the ways in which their opinions and knowledge changed through deliberation.

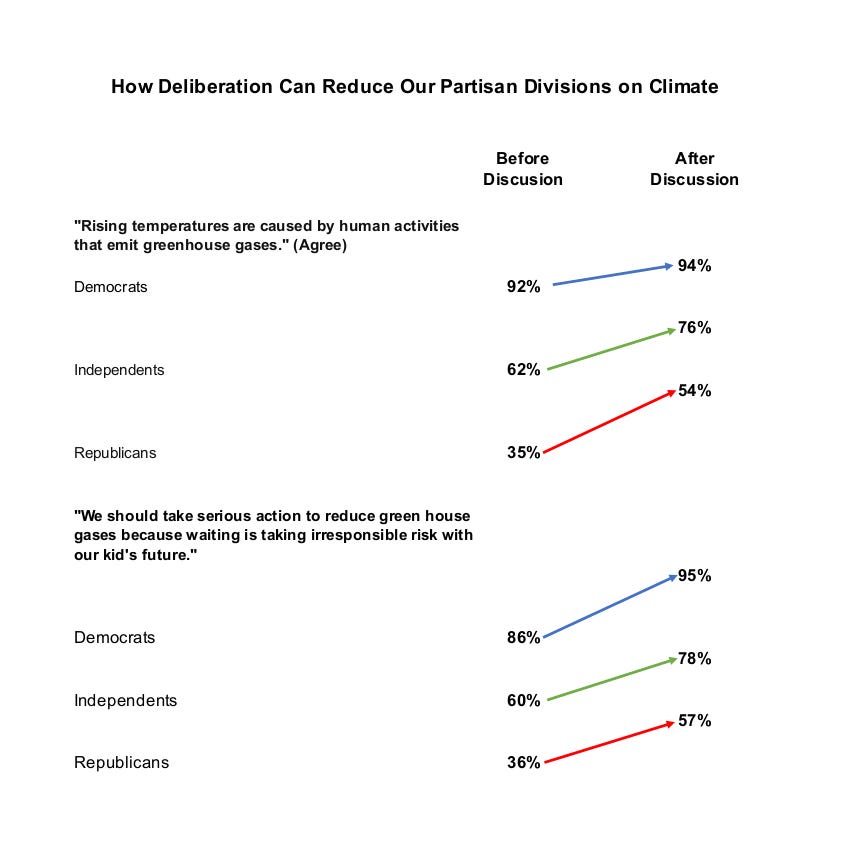

The responses before deliberation reveal a chasm between political parties. Only 35 percent of Republicans but 92 percent of Democrats initially saw rising temperatures as “caused by human activities that emit greenhouse gases.” After deliberation, Republican agreement with this view increased nineteen percentage points to 54 percent, a majority; agreement in the overall sample rose from two-thirds to three-quarters. Republicans and the overall sample changed almost identically on the need to get to net zero greenhouse gas emissions in order to halt the rise in global temperatures.

The same pattern held for many specific energy policies. While Democrats remained more supportive of most forms of action on climate change, the differences between the two groups of partisans narrowed dramatically. Republicans joined Democrats and Independents in majority support for eliminating emissions from coal; creating incentives for carbon capture and storage; investing in hydrogen as a new energy source; providing incentives to manufacturers to produce electric cars; developing a new generation of nuclear energy; limiting emissions in electricity production; and “creating strong incentives” for other nations to join the United States in a rapid “transition to a Net Zero global economy.”

Some significant differences remained after deliberating, but they were mostly about the timetable. Republicans were far more likely to question a 2050 target for reaching net zero, eliminating the sale of all new gas- and diesel-powered cars by 2035, and requiring all-electric new buildings and major appliances by 2035. Still, the Republicans significantly increased their support for climate action on sixty-six of the seventy-two questions.

Participants overall became more knowledgeable about climate change, with the average proportion of correct answers rising significantly from 62 to 78 percent; and they emerged with a greatly increased sense that they had “opinions worth listening to.”

But what good is an experiment when most people are stuck in their “filter bubbles” and many do not think about these issues at all? Despite the horrible storms, floods, droughts, and wildfires that beset the country this summer, the control group, which did not deliberate, barely budged in its views on climate.

We conducted this experiment on an automated platform that allows any group to moderate its own video-based discussions. It showed the power of balanced, evidence-based, civil dialogue in transforming opinion. But there is no reason why such applications should be limited to less than a thousand Americans deliberating in 104 small groups. In theory, it could be applied to any number. Even more consequential would be to muster the many elements of our civil society—churches, schools, and community groups—to foster open-minded and balanced discussions in contexts that make people feel informed and valued enough not just to weigh the tradeoffs between different policy options, but to do so together, with one another.

Nine hundred sixty-two Americans have just shown that it is possible to put aside bitter partisan divides and think together in a civic spirit. Now it is time to enlarge that number many times over, so that we can fashion innovative solutions to our twin crises of climate change and our democracy itself.

James Fishkin is the Janet M. Peck Chair in International Communication at Stanford University, where he directs the Center for Deliberative Democracy.

Larry Diamond, an editorial board member of American Purpose, is a senior fellow at the Hoover Institution and the Freeman Spogli Institute for International Studies at Stanford University.