It's Time To Stop Being Carried Away By Conspiracy Theories

What if it turns out that the global elite wasn’t actually implicated in Epstein’s sex crimes?

Recently, I’ve been in a situation where I had to engage in a lot of small talk. My favorite icebreaker: what do you think is really in the Epstein Files?

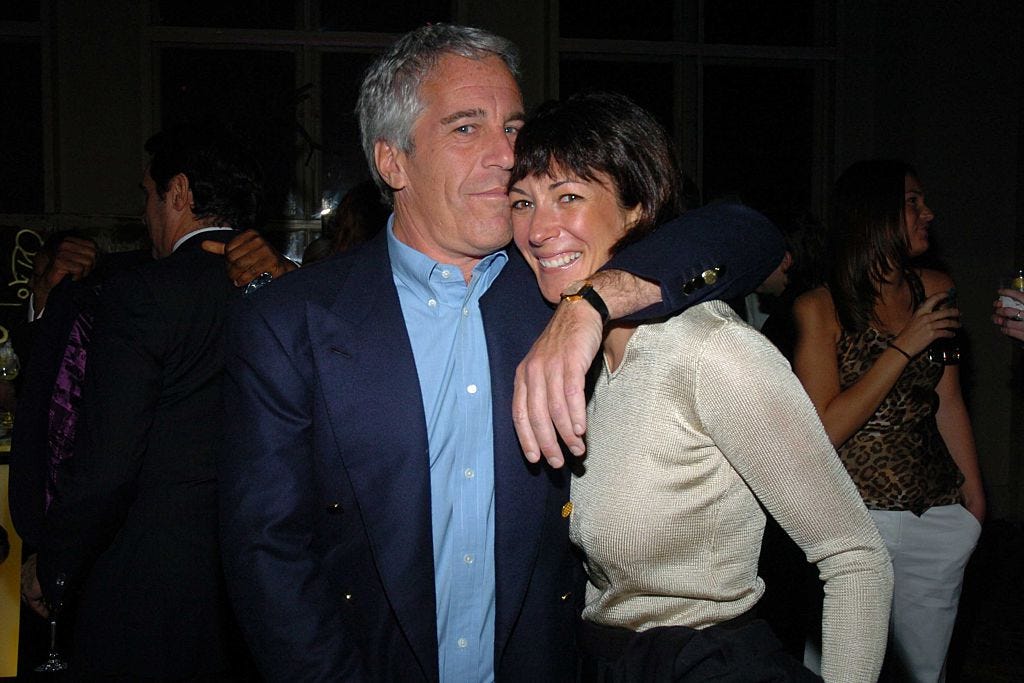

That works wonders actually—especially with men of a certain age (asking who they think killed JFK can work too, but that’s more of a niche audience)—and it seemed to reach a fever pitch in July when, just like in anybody’s favorite thriller, Deputy Attorney General Todd Blanche, doing his best imitation of Clarice Starling headed into a maximum-security prison to interview Hannibal Lecter, flew to Tallahassee, Florida, to interview Epstein associate and child sex trafficker Ghislaine Maxwell and finally get to the bottom of the Epstein case only to be told… basically, nothing at all.

Our culture has gotten to enough of a bizarro place that, even for staid, mainstream outlets, Ghislaine’s two days of denials were basically proof that… she was hiding something. Here’s how The New Yorker reported it: “To read the transcript is to be enraged … by Blanche’s placid acceptance of her version of events. … The interview was a damage-control operation.” And The New York Times spent its summary of the interview berating Blanche for not asking different questions and finishing with the suggestive conclusion, based on a Blanche non-question, that Epstein may well have been working for Mossad after all. But there was one line of Ghislaine’s that really got to me. She said, “People have gone and lost their minds for this thing. … He’s not that interesting.”

And I found myself wondering—even if this makes me sound like a real crank—whether there isn’t actually that much to the Epstein story (at least the aspect of it involving myriad other members of the rich and powerful participating in his underage sex trafficking ring), and Ghislaine Maxwell is kind of making a valid point here actually, and conspiracies aren’t really real, the world being made of much grayer stuff than that, and, oh by the way, Santa Claus actually is mom and dad scampering around the Goodwill on December 24th and grabbing as much cheap merch as they think will fill a stocking.

As New York Times columnist David French put it, the Epstein case has become something like “the thinking man’s version of the QAnon theory.” Believe that Epstein was bumped off in prison; or that all kinds of powerful people were having sex with underage girls on Epstein’s plane, the so-called “Lolita Express”; or that Epstein was some kind of kingpin in a vast, international “sex trafficking network,” as staffers of Senator Ron Wyden described it to The New York Times; or that Epstein “belonged to intelligence,” as one much-recycled claim first reported on by The Daily Beast had it, and it’s like a gateway drug into all kinds of other dizzying possibilities, of how sex and espionage and finance interweave amongst the elite of the elite, and what the real shape of power is. Partake of this chain of thought, and it can get pretty heady—and, over fried food or sitting next to casual acquaintances on airplanes, I’ve been right there with the glue-sniffers in imagining some very lurid tales about honey traps and kompromat and intelligence agencies working with Epstein in much the same way, incidentally, that they were alleged to have worked with Ghislaine Maxwell’s father.

But the cold shower of Maxwell’s prison testimony—with her immunity at stake, mind you, and with Maxwell liable for further prosecution if caught in a lie—raises the possibility that there is less here than meets the eye. And if the Epstein case turns out to be, at least from the perspective of honey traps and kompromat and international sex-trafficking syndicates of pure evil, a relative Nothingburger, then it may be worth taking a good hard look in the mirror and asking ourselves if our wild imaginations have gotten away from us.

To be clear, I’m not saying there’s nothing at all there. Epstein was duly convicted for (with help from Maxwell) procuring prostitution from minors and before his death was facing charges for trafficking and conspiracy to traffic minors. Julie K. Brown, the Miami Herald reporter who did more than anybody else to break the story, estimates that the number of victims in the Palm Beach house alone runs into the hundreds, and—as she put it to Ross Douthat—“These girls’ lives were essentially ruined, even if they had gone to his house only one time … it affected the rest of their lives, and the stories that they were telling me were just incredibly powerful.”

But as reporter Will Sommer, a conspiracy theory specialist, contended in an interview with Ezra Klein: “I think it’s very possible that Jeffrey Epstein was a guy with a lot of powerful friends who was incidentally a pedophile, and that these powerful people were not involved with that aspect of his life.” Or as Maxwell said from prison (with all due disclaimers applying): “A [powerful] man wants sexual favors, he will find that. They didn’t have to come to Epstein for that.”

Stick with what’s actually proven about Epstein—as opposed to the more far-flung insinuations—and the story cuts itself down to size very quickly. In August, The New York Times breathlessly reported a look into Epstein’s “Manhattan lair.” But read beyond that and the “lair” sounds awfully like a well-appointed townhouse where dinner guests experienced lousy spreads, ready-at-hand chalkboards where they could “sketch out a diagram or write a mathematical formula,” and—the pièce de resistance—an entomologist. The presence of young female servers was remarked upon by guests, but The Times’ piece had no stronger evidence that guests were complicit in Epstein’s sex crimes than the fact that a first edition of Lolita was prominently “showcased.” Meanwhile, today’s front page piece investigated JPMorgan’s “enabling” of Epstein, which seemed largely to boil down to JPMorgan’s being a bank that allowed its client to withdraw his own money, sometimes in denominations of the tens of thousands. “Cash is a currency of criminals,” The Times’ summary noted. Which is true. But cash is also a currency of everybody else as well. (It turned out that Epstein had been transferring huge sums of money to his victims, and that the bank’s internal safety mechanisms maybe should have treated this as suspicious—but it is a stretch to claim that it is complicit in “enabling” his crimes.) Similarly, there’s good reason to think that the creepy “temple” on Epstein Island—the epicenter of many a conspiracy theory—may well have been a music pavilion after all.

And if some of Epstein’s victims have claimed they were trafficked to other powerful men, not all those claims have stood up to closer scrutiny. Virginia Giuffre, the best known, said, for instance, in her 2016 deposition, “There’s a whole bunch that I just—it’s hard for me to remember them all.” Her list of positive IDs ended up including former Senate Majority Leader George Mitchell, famed lawyer Alan Dershowitz, former governor Bill Richardson, Prince Andrew, “another prince, I don’t know his name,” and “another foreign president, I can’t remember his name, he was Spanish.” Giuffre reached a settlement with Prince Andrew, but Dershowitz proved to have the perfect alibi of looking like every other old Jewish man and, in 2022, elicited from Giuffre the statement that “I may have made a mistake in identifying Mr. Dershowitz.” There has been little concrete follow-up on the other accusations. People like Ezra Klein and Ross Douthat, who seem to be on extended furlough from the usual gamut of opining in order to pursue some promising leads in the cold case, have admitted the possibility that the Epstein story may return back to the realm of mundanity: that he was a mere multi-millionaire, as opposed to a billionaire, and, like everybody else on the planet, was living somewhat beyond his means. “At the end of the day … his estate was not that large,” Klein noted. And a great deal of his sinister network, when shaken out and viewed from a different direction, comes to look like run-of-the-mill social climbing.

In other words, it may be time to rein it in. The society has gotten itself into a state where it’s only conspiracy theories that really make sense to us, where Joe Rogan—open-minded and of the people—has become our Walter Cronkite, where we just can’t deal with the possibility that power more often than not tends to reside in overwhelmed people dealing with imperfect means. The ubiquitous impulse to view Epstein as a parable of power may say more about us than it does him.

There was a vivid illustration of where conspiracy thinking leads in the Minneapolis attack last week. It may in turn be a conspiracy theory to imagine that Robin Westman, the shooter, was involved in 764, a nihilistic online group dedicated to sowing mayhem, but there’s no question that Westman spent way too much time online, living in an almost entirely gamified, phantasmagoric reality where the taking of life had virtually no meaning and everything connected to the titillation of shock. If August is always Conspiracy Month, the Minneapolis shooting, coming at the month’s end, was a brutal bookend to it. We all like to play these games in our mind—with our various thinking man’s QAnons—but the games have a way of leading us into spiraling fantasias.

What the prevalence of conspiracy thinking seems really to be about is two factors. One is of course social media and online chatter built around the feed of suggestive thinking. Internet discourse works very differently than discourse in the heyday of print or television media. There, the basic unit was the “story”—the news event, which could fit neatly between commercial breaks and was delivered always with breathless excitement before being taken out and discarded at the end of the day almost exactly like a coffee shop cleaning out its wares and preparing for the next day’s rush. In the social media era, the basic unit is the drip, is something happening somewhere in the world (and Epstein is really perfect for this) that people can add to, can offer their theories about and detract from others’, with all of it at some point leaving behind the creepy financier at the heart of it and becoming a vast discourse unto itself. And then the other factor fueling conspiracy thinking is, paradoxically enough, the weakness of the elites. The all-powerful cabal really seems to have been suffering a series of reverses recently—they have had a conspicuously difficult time, for instance, keeping Donald Trump out of office—but it’s really not very fun to imagine that the Democratic Party is broke and dysfunctional, that the Deep State is facing severe funding cuts, that, in any case, power isn’t really constituted of people sitting in pleasant control over everything and manipulating reality as they wish but always involves warring factions hanging on for dear life to whatever it is they have. And so the response of the good conspiracy theorist is to dig ever deeper and to imagine the levers of power being controlled by people like Epstein hiding in the decadent shadows.

It’s really been great fun in a lot of ways to be part of the culture taking its turn into the conspiratorial. But it’s also basically a juvenile way of thinking. And it’s thinking like that that did a great deal to propel Trump into the White House—to imagine that, for instance, Kamala Harris was a pawn of dark interests whispering into her Nova H1 earpiece during a presidential debate and that, if Trump was in many ways a difficult person, he was also refreshingly free of the power elite. We seem to be paying the price for that now. We all went berserk together, with Trump doing as much as anybody to fan the flames of conspiracy, and we’ve now reached the absurd situation where The Times is prowling around “lairs” that look an awful lot like townhouses and where its idea of a smoking gun is withdrawing cash or owning a copy of Lolita. Maybe the Epstein story scratches the surface of something deeply true about the power elite. But maybe it doesn’t. Maybe, as Maxwell said from prison of Epstein, “He’s a disgusting guy who did terrible things to young kids,” and it doesn’t really go much beyond that—and we’re trying to will into being some narrative about power that is largely our own fantasy.

At some point the conspiracy theories wandered from being fun and idle speculation to really being—more than we’re probably ready to acknowledge—how our culture understands itself. That’s gone a long way towards breaking our basic sense of trust in each other, as well as the reality-principle itself. This might be a good time to take it down a notch. As tempting as it is, when faced with a bout of small talk, to start with the time-gap in the surveillance cameras surrounding Epstein’s cell—and, next thing you know, to find yourself whiling away the afternoon discussing the merits of the Grassy Knoll as opposed to the Book Depository as the place to get a clear shot off on JFK—maybe it’s healthier all around to try asking after people’s kids or favorite sports teams instead. Maybe now’s the time to get a grip.

Sam Kahn is associate editor at Persuasion and writes the Substack Castalia.

Follow Persuasion on X, LinkedIn, and YouTube to keep up with our latest articles, podcasts, and events, as well as updates from excellent writers across our network.

And, to receive pieces like this in your inbox and support our work, subscribe below:

Uh, Sam, even if we assume for the sake of argument that all there is to the story was that Epstein raped hundreds of underage girls and got away with it for years, it's still a big deal! Do I really have to explain that?

I think that Sam nails it with “Power isn’t really constituted of people sitting in pleasant control over everything and manipulating reality as they wish but always involves warring factions hanging on for dear life to whatever it is they have.”