James Baldwin’s Radicalism

One of America’s most perceptive writers rejected the politics of division. He has much to teach us about race and injustice today.

By Sahil Handa

The first time I read James Baldwin, I didn’t know he was black. I was a skinny, 17-year-old Indian boy with braces, and when I picked up a slim novel called Giovanni’s Room, I finished it in a week. I loved it—so much so that I gave it to my mother and asked her to read it. She did, and thought it was my way of coming out as gay.

It never crossed my mind that Baldwin might be black because the novel does not contain a single black character. The novel’s protagonist, David, is white, and Baldwin once told an interviewer that David could have been white, black, or yellow: “In terms of what happened to him, none of that mattered at all.”

What does happen to David in Giovanni’s Room is about love, and I was disastrously afraid of love. My last relationship—then my only relationship—had left me feeling like a fool for ever having believed in the word. In the novel, David spends weeks living with Giovanni, his gay partner, in a cold, claustrophobic room. As 16-year-olds in love for the first time, my girlfriend and I had spent practically all of our relationship in a room—not a tiny, plastered room in Paris, the setting for Baldwin’s story, but an airy, pink-walled girl’s bedroom in North London. I had up until that point not imagined that love could apply to me. It had felt like a fairy tale. Needless to say, it did not turn out like one.

Baldwin taught me to let go of my childish perception of love. He taught me that facing my boyish insecurities—my protruding braces, my big nose, my hairy legs, and my impure thoughts—had just as much to do with love as the fairy tales. Baldwin wrote Giovanni’s Room as a story about the failure of innocence; reading it forced me to realize that I had been the victim of my own.

My youthful state of romantic insecurity is not the subject of this essay. But I include it here because I think that I would have encountered an altogether different Baldwin if I had first come across his name in a different way. Baldwin has been quoted on almost every anti-racist reading list in recent months, and if I had first found him on one of these lists, I would likely now view him as simply another fierce spokesman for black America and enemy to white supremacy. Baldwin was both of these things, but they do not exhaust his identity. Interpreting him through so narrow a lens does a disservice to everything he can teach us about the problem of race and identity in American life.

I first encountered Baldwin because he taught me something about love, and that necessarily colored everything that he had to teach me about color. And he taught me about color through a series of letters to an America that, for all its toxic obsession with color, he could not help but love.

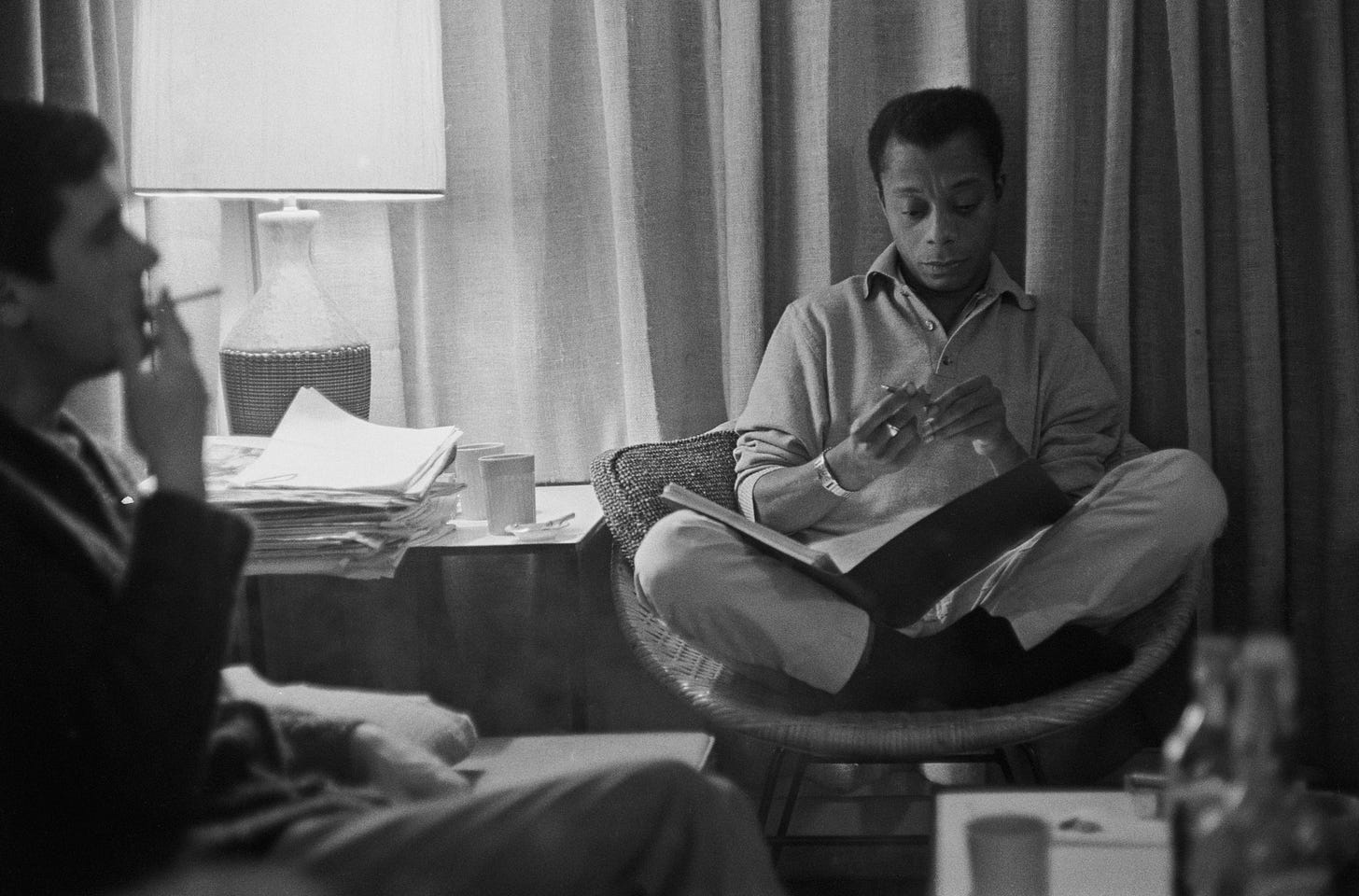

Baldwin had deep, blinking eyes: the kind of eyes that make you feel like they are watching you when you aren’t watching them. When he sat and spoke, his body would rise from the chair with the crescendo of his voice. The body was small, fidgety, and feline. But the voice—over-pronounced, biting, with an eloquent drawl—was at once menacing and disarming, rapturous and threatening. It was an outcome of early years immersed in the Bible, the black church, Emerson, Henry James, Dickens, and Dostoyevsky. On the page, it translated into winding, elegant, enchanting sentences.

His early years were spent in Harlem, New York, where young “Jimmy” was born in 1924. This was the Harlem of the projects, extreme poverty, and race riots. Baldwin’s dad was a preacher, and he died when his son was 18. His encounters with Christianity form the first half of the work for which he is most famous—a two-part essay called The Fire Next Time—and the background for his semi-autobiographical novel, Go Tell It on the Mountain. The first got Baldwin accused of being an assimilationist. The second got him accused of turning his back on the African-American experience. Both accusations amounted to the same charge: that Baldwin wasn’t sufficiently black. The charge is based on the premise that there is such a thing as being black—and that such a thing is worth protecting. Baldwin never accepted this premise.

The explicit subject of The Fire Next Time was Baldwin’s encounter with the Nation of Islam, the black separatist movement that had attracted Malcolm X to its ranks, prophesizing that all white people were cursed and that blacks ought to have as little to do with them as possible. Baldwin’s piece was commissioned for Commentary by the magazine’s then-liberal editor, Norman Podhoretz, who thought Baldwin would be able to convey “the growing appeal of Malcolm’s message” while holding out against its “pernicious ideology.”

Podhoretz detested the separatist ideology because he thought it “painted white people as the devil.” But in his essay, Baldwin noticed a deeper problem: that it painted black people as God.

“God is black,” they say. “All black men belong to Islam; they have been chosen. And Islam shall rule the world.”

Whites are immune from virtue, and blacks immune from sin: “The dream, the sentiment is old ... Only the color is new.” The result could only be “spiritual wasteland.”

As Baldwin saw it, this was not a problem limited to the Nation of Islam: He thought the same destructive pride dogged the black church of his youth. Ministers seemed to suggest that there was a special place in heaven for people who shared Baldwin’s skin color, and that black Americans’ love for the Lord could be measured by their distrust of whites. But for Baldwin, this was a myth, just as the idea of a black Muslim world order was a myth. They were both black myths just as the idea of a flawless, freedom-loving American nation was a white myth. All of these myths were masks, he wrote, “for hatred and self-hatred and despair.”

Nevertheless, Baldwin retained an unquenchable love for black solidarity, forged through a history of survival. “In spite of everything,” he wrote, “there was in the life I fled a zest and a joy and a capacity for facing and surviving disaster that are very moving and very rare. Perhaps we were, all of us—pimps, whores, racketeers, church members, and children—bound together by the nature of our oppression.” His refusal to label white people in Manichean terms was always paired with the insistence that America was covered by a blanket of racism. Though he disagreed with the separatist project, Baldwin thought Malcolm X was right to point out that when it came to violence, there was one standard for whites and another standard for everyone else.

It was a tension characteristic of Baldwin, and it is part of the reason he has been read in so many different ways. He was accused of being an assimilationist—a dirty word for an integrationist—but he was also accused of being a militant who refused to recognize the racial progress that occurred during his lifetime. He never personally identified with the “integrationist” label, no matter how many times it was thrown at him. And in 1969, on “The Dick Cavett Show,” he went so far as to tell a predominantly white television audience that the pursuit of integration was equivalent to white supremacy.

Baldwin did not want blacks to be “integrated” into a burning house—and America had, as he saw it, been burning since its beginnings. “I cannot accept the proposition that the four-hundred-year travail of the American Negro should result merely in his attainment of the present level of the American civilization,” he argued. Instead, Americans were in need of new standards for how to live, and black America was the key to finding them: “The price of this transformation is the unconditional freedom of the Negro … the American future is precisely as bright or as dark as his.”

At the same time, Baldwin did not think that the contribution blacks could make to the American project had anything inherently to do with the fact that they were black. “I have great respect for that unsung army of black men and women” in American history, he wrote. However, “I am proud of these people not because of their color but because of their intelligence and their spiritual force and their beauty.”

If separatism encouraged a dangerous fixation with race, Baldwin believed that it was also something of an illusion. The American Negro had been formed in America, and he did not have a future anywhere else. America contained the source of both his subjugation and his possible freedom: “In short, we, the black and the white, deeply need each other here if we are really to become a nation—if we are really, that is, to achieve our identity, our maturity, as men and women. To create one nation has proved to be a hideously difficult task; there is no need now to create two.”

Baldwin did not want a white nation, and he did not want a black nation; but neither did he want an America that was white and black. Baldwin wanted to build a nation that was neither white nor black: a nation of individuals who were more concerned with what lay inside each other’s skin than outside.

Baldwin loved America in the same way that he loved himself: fiercely, relentlessly and, most of all, critically. Contained within the country’s ruinous past was a magnificent potential that would never be fulfilled by reifying the categories of color that had trapped it in a racial hierarchy since its birth. Racial progress needed to contend with both catastrophe and reality at once; it needed to recognize the political fact of skin color—and the suffering it would continue to bring—while insisting that “the value placed on the color of the skin is always and everywhere and forever a delusion.” This demanded a magnanimity from blacks that could hardly be justified by American history. Yet it was, Baldwin saw, the only way blacks could seize their own freedom in a country that had never previously accepted them. “I know that what I am asking is impossible,” he wrote. “But in our time, as in every time, the impossible is the least that one can demand.”

As Baldwin began to teach at universities across the country, he saw firsthand that much of the elite discussion about race relations was oblivious to the reality facing most black people—particularly working-class black people—on the ground. In a late essay titled Dark Days written in 1980, seven years before his death, he wrote the following about his experiencing teaching at Bowling Green State University in Ohio: “One of my white students, in a racially mixed class, asked me, ‘Why does the white hate the nigger?’ … The subject, I confess, frightened me, and it would never have occurred to me to throw it at them so nakedly.”

But once the matter was out in the open, the students began to talk openly. “In the ensuing discussion the children, very soon, did not need me at all … They began talking to one another, and they were not talking about race. They were talking of their desire to know one another, their need to know one another … They were trying to put themselves and their country together.”

They did not discuss race, Baldwin wrote, because they no longer cared about race. Where their skin lay on the spectrum of color—whether they were “tea, coffee, chocolate, mocha, honey, eggplant,” or “eggplant coated with red pepper”—was as irrelevant to their conversations as the number of hairs on their head. The students were repulsed by racism, but they did not express that repulsion by acting as though race was destined to dominate their lives. Nor did they set down rules for interracial dialogue: If they were going to get to know each other, they needed to understand each other. “In order to have a conversation with someone you have to reveal yourself,” Baldwin wrote, many years earlier. “In order to have a real relationship with somebody you have got to take the risk of being thought, God forbid, an oddball.”

Being thought an oddball is not incentivized by much of our current polarized racial discourse. Indeed, in elite institutions, it is something that is more and more frequently avoided at all costs. One is either racist or anti-racist; white or black; with us or against us; an ally or an enemy. Thinking about one’s “privilege” is a task set aside for certain people; and for those who are asked to turn inside and question themselves, they are told to make every effort to keep silent if what they find does not match what they have been told they ought to find.

But the reason that Baldwin’s work has such resonance is that he saw that politics could only be conducted by equal participants, just as two lovers could only build a relationship by opening their hearts on equal terms. He recognized the incongruities beneath his identity, the impurities beneath his intentions, and the pragmatism beneath his politics. He did not present himself or black people as innocent, and others—white people—as guilty. He tried to do something more honest. He tried to show that he, every other person, and therefore America, was a mixture of both. Blacks had every right to be angry at America. But an America that lived up to the standard of human freedom required that every person involved in that project do everything to preserve the state of their own heart.

In 1998, The New York Times published a critical review of Baldwin’s work that argued that he was an absolutist looking for a moral cataclysm that would never come: Despite “living through a wrenching, altogether extraordinary social revolution, he forever was tormented—cursed … Little wonder he lost his audience: America did what Baldwin could not—it moved forward.” If the events of the last year have proved anything, it is that though America may have moved forward, it has not moved on. The election of a black man as president did not move America on because it did not fundamentally change the living reality for most working-class black Americans. America’s racial wound was never fully healed.

But the realization of this fact has led some progressives to assume that the correct response is to elevate the role that skin color plays in society. These self-described anti-racists sacrifice the pursuit of opening hearts in order to denounce closed minds, setting purity tests for what counts as black opinion and essentializing our notion of whiteness alongside. As they label every institution eternally and systemically racist, they lose the plurality of individual perspectives in favor of a frivolous ostentation, papering over the stubborn influence of race and class in American society with the language of diversity and inclusion.

Politics is a game of competing stories about national identity. And in our present moment, too many people are trying to tell a shallow story. James Baldwin did not tell a shallow story. Nor did he tell a black and white story. He asked people to discover an entirely new story: We made the world we’re living in and we have to make it over.

For now, our stories are too simple, our labels too rigid, and our hearts too closed to the contingency of our histories. Creating a new national identity means confronting the horrors that we face as a collective and finding what we have in common; emphasizing the promise of America, the paranoia in America, and the potential love that lies deep in America.

The first thing Baldwin taught me about color was that it paled in comparison to the power of love: that such a superficial fact does no justice to the complexity of the self. “No one in the world—in the entire world—knows more—knows Americans better or, odd as this may sound, loves them more than the American negro,” he wrote. “This is because he has had to watch you, outwit you, deal with you, and bear you, and sometimes even bleed and die with you, ever since we got here, that is, both of us, black and white, got here—and this is a wedding. Whether I like it or not, or whether you like it or not, we are bound together forever.”

“The one thing all Americans have in common,” Baldwin continued, “is that they have no identity apart from the identity which is being achieved on this continent.”

Sahil Handa is an associate editor at Persuasion and is working on a book about the campus conformity crisis.

A version of this article originally appeared in Discourse on August 2, 2021. It is reprinted with permission.

This is such a brilliant and beautiful essay- there is so much here that needs to be said again and again- that I want to keep on reading it for a long time, the way one might like to keep eating a piece of delicious cake for a long time, longer than it actually takes to consume it.

James Baldwin showed us the way but too few have grasped his words or even listened.