Lessons in Freedom From the Puritans

Neither license nor moralism will solve the ills that plague our society.

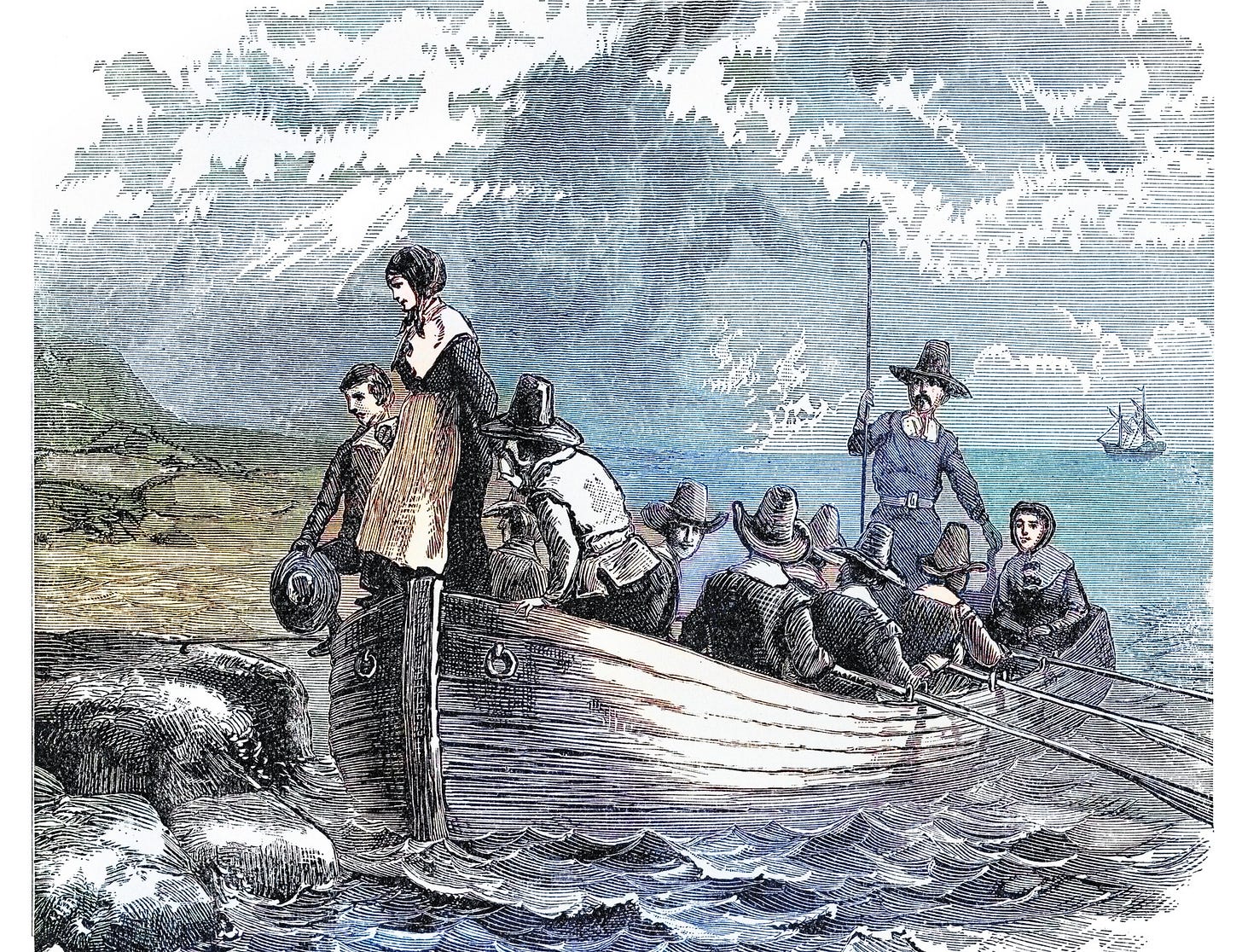

For most of us, the image of the first American Thanksgiving is an oddly vivid one: Pilgrims in their Puritanical garb sitting down to a massive feast with their Native American allies. Recently, historians have relished pointing out the severe inaccuracies and contradictions of this common picture—the first Thanksgiving was unlikely to have served turkey, and in just a hundred years these “peaceful pilgrims” from Europe had wiped out almost the entire Native American population of the region.

Yet our idyllic imaginings are more revealing than they are often given credit for. If nothing else, they help to capture the image Puritan settlers had of themselves—a peaceful people journeying to a new world to establish a selfless, god-loving community. At the heart of this vision lay a conception of human liberty as a communal project that disentangles us from our selfish impulses. Our modern age of social media vanity projects and mass reactionary movements could learn a lot from the Puritans’ vision—and from why it ultimately failed.

The people we now call pilgrims or Puritans were English religious separatists influenced by the theology of John Calvin. Calvin and his followers differentiated themselves from their fellow Protestants in two main ways. First, Calvinists see humans as totally depraved. In their view, without the direct intervention of God, we have no hope at all of personal improvement or redemption. One consequence of this is that humans do not have free will. Instead, every minor movement in creation is exercised directly by the hand of God.

The second distinct principle of Calvinism is a complete repudiation of the religious and political hierarchies of the Roman Catholic Church. Instead, Calvinism has long tended towards a more firmly congregational form of church governance—one where the parishioners as a whole, or through elected representatives, determine the destiny of each individual church. This view of church governance affected the Puritan view of politics more broadly, and most Calvinists prefer some form of democratic self-government to aristocracy or monarchy.

These two religious beliefs conflicted with the political and theological outlook of England during the pilgrims’ time. Social divisions helped contribute to the English Civil War, and when the monarchy was restored in 1660 many Puritans wished to find a home that more directly reflected their beliefs. Coming in several groups, these Puritans started to immigrate to the “new world” of North America to try and build the ideal Christian society.

The first big question that faced the Puritans was exactly how they would translate their religion into a political system. In a speech delivered to his fellow settlers before they went to shore, the leader of the Massachusetts Bay Colony, John Winthrop, tried to answer this question. He started by outlining the core virtue of all good Christians: charity. The reason Christians are obligated to be charitable is a simple one:

All true Christians are of one body in Christ … All parts of this body being thus united are made contiguous in a special relation as they must take part in each other’s strengths and infirmities … If one member suffers, all suffer with it; if one be in honor all rejoice with it.

Put more simply, John Winthrop argued that all people are linked together by a common humanity—and therefore are all fundamentally equal. This window into human nature is the cornerstone of Puritan political life, one that does not depart all that greatly from the idea of human dignity that is so central to liberalism and Christian democracy today.

For the Puritans, this political foundation was the only sure path to human freedom. In their view, we attain liberty by recognizing God in our fellow man and coming to love one another. When we do this, we start to see the importance of living in a community—of living and governing with our fellow creatures.

In a different speech, Winthrop built upon this outlook by arguing that there are two types of freedom. The first he called “natural” because it is held “common to man and beasts.” It is characterized by the ability of people to do whatever they want. Winthrop makes no secret of his disdain for natural freedom, which he argues quickly degenerates into selfishness. If we are only worried about doing whatever we want, there is very little to make us care about others.

Winthrop preferred a second sort of freedom, which he called “federal” or “civil liberty.” He described it as “the proper end and object of authority and cannot subsist without it; and it is liberty to that only which is good, just, and honest.” This, he argues, is the liberty of being a member of a community. In a sense, Winthrop was saying that we have to shackle ourselves to be truly free; that we must subject ourselves to God and our fellow man. For the Puritans, freedom must be bound with selflessness and virtue—a state of the soul that is made more likely when we are immersed in a community that forces us to think about more than just ourselves.

It is for this reason that Puritan society was one of the most democratic civilizations since Athens. The day-to-day business of politics was handled in town hall meetings where citizens could directly contribute to policy-making. Puritan society fostered a high level of education to prepare future citizens for political life and an impressively wide electorate (for the time) that included almost all adult males.

As I have argued elsewhere, much of the rebellion against today’s political establishment in the West stems from a belief on the part of citizens that they no longer control their own destinies. Likewise, the collapse of selflessness and a shared conception of virtue has contributed to a political climate that is increasingly acrimonious and selfish. Could the politics advocated by the Puritans therefore correct some of the most serious defects of the modern age?

On the one hand, modernity has adopted wholesale what Winthrop calls “natural freedom,” with the result—as the Puritans would have predicted—that we have become more animalistic. As Jean-Jacques Rousseau knew, modern society makes people vain and selfish. We no longer live for ourselves but instead live for the praise and adulation of others. All of this has been compounded by social media, whose sole purpose seems to be to perpetuate a culture of vanity that consumes us. As a result, there is much to recommend John Winthrop’s condemnation of freedom-as-license and his emphasis on the importance of civil freedom over natural freedom.

Yet the Puritan emphasis on community came at a cost. Nobody understood or more vividly captured the problems of Puritan society than Nathaniel Hawthorne. Himself a devotee of democratic regimes (and an early intellectual influence on the Democratic Party), Hawthorne sought to highlight the innate hypocrisy and cruelty of utopian projects. His favorite target for criticism was the early Puritan society of his native New England.

Hawthorne’s lesser-known short story “The May-Pole of Merry Mount” cogently captures this. The story opens with the inhabitants of a sleepy New England village celebrating the wedding of a young couple by dancing around a tall, beribboned maypole. But the celebrations are interrupted by the Puritan leader John Endicott, who orders that the maypole be cut down and the people of Merry Mount whipped for their indecency. Endicott’s followers quickly oblige. In the end, he shows a small amount of leniency to the new couple and simply orders them to dress more conservatively, though the other attendees at the wedding are savagely whipped.

This brief story highlights the high cost of a Puritan account of freedom—the total suppression of individuality and self-expression. Hawthorne makes clear the stakes in the narrative: New England at the time was divided between the forces of “gloom” and “jollity,” each struggling to establish its own American empire. Though it was unclear who the ultimate victor would be, it is entirely obvious that gloom triumphs in the Battle of Merry Mount. All of this challenges the merits of Puritan freedom.

Puritans so thoroughly concentrated on the importance of community and virtue that they forgot that society is still composed of individuals. Helping people care about others is important for building a genuinely free society. But forcing them to act selflessly does little to make them selfless in their hearts. To put this differently, selflessness is important to freedom, but it is a state of the human soul every bit as much as it is a way of behaving. For this reason, as the Roman statesman Cicero argued hundreds of years before Hawthorne, goodness cannot be coerced by the state or the community.

Hawthorne’s story reveals the inevitable outcome of coercing rather than cultivating virtue: a community that gives into its natural propensities for violence and oppression. John Endicott, with his suppression of the maypole dance, does more than simply foist his own rigid moral standards on others; he pursues an outlet for his very human desire for power and control. This theme is even more obvious in Hawthorne’s masterwork The Scarlet Letter, in which the unfortunate Hester Prynne has a child out of wedlock and as punishment is forced by the village to wear a scarlet letter A (for adulterer) on her chest. Throughout the novel, it is apparent that the villagers have inflicted this unusual punishment upon Hester not just because she defied biblical teaching but because they genuinely delight in her suffering. Hawthorne masterfully portrays how a society without any regard for the individual can easily become an outlet not for the cultivation of virtue but for the most vicious of human impulses.

The reactionary moralists who now dominate much of the intellectual right echo the Puritans described by Hawthorne. They begin with the accurate assessment that virtue is not something each of us determines for ourselves and that humans only truly flourish when we do things as a community. But rather than encourage community-building from the ground up in a way that respects moral pluralism, intellectuals such as Adrian Vermeule or politicians such as JD Vance seek to turn the government and courts into active arbiters of right and wrong. Whether motivated by a personal desire for authority or simple confusion the result is the same—we may lose our obsession with individualism, but in the process we will also lose ourselves.

The Puritans offer a cautionary tale of what we should and should not do in our own attempts to secure a more robust freedom. John Winthrop was completely correct that the freedom to do whatever we want does nothing to differentiate man from beast, and can cause society to degenerate into a war of self interest. In our contemporary moment, we have perhaps forgotten this important reality—veering heavily into a culture where everyone is submerged in an ocean of their own selfishness. If you walk up to the average person on the street and ask them what freedom is, they will likely say some variation of “doing whatever you want.” This understanding of freedom as license is appealing for obvious reasons, but it has led to a selfish, unhappy, and restless generation.

At the same time, the Puritans also warn us to be careful about how we correct the individualism of the modern age. Many who understand society’s ills move in the opposite direction—they see a listless civilization and argue that the only cure is harsh moral prescription. In truth, neither laissez-faire liberty nor reactionary morals are the solution to the ills that plague our society. We have to find a middle ground. After all, there would be no greater tragedy than vanquishing the despotism of the self only to plunge into the despotism of the collective.

Jeffery Tyler Syck is an Assistant Professor of Politics and the Director of the Center for Public Service at the University of Pikeville in his native Kentucky.

Follow Persuasion on X, LinkedIn, and YouTube to keep up with our latest articles, podcasts, and events, as well as updates from excellent writers across our network.

And, to receive pieces like this in your inbox and support our work, subscribe below:

The problem with this analysis is that it leaves out the Puritan determination to rid themselves of anyone who didn’t follow the authoritarian rule of the ministers. The most egregious example of this were the Salem witchcraft trials, but one can also point to the expulsion of Ann Hutchinson and her family and others. It also fails to mention the hanging of Quakers who dared to attempt to bring their brand of faith.

And it fails to account for the Calvinistic concert of The Elect - that some were to be saved and some were not based on a Divine selection that preceded birth. Calvin’s Geneva was not a place of freedom.

Indeed, the one thing that has characterized elements of the conservative right, and even more so in Trumpism is the idea that only some of us are worthy of being considered ‘real’ Americans. Many of the rest, of course, are ‘the enemies within; much as were the ‘witches' of Salem.

While there are many valid criticisms of the Puritan project here, the author relies almost entirely upon the fictional work of Nathaniel Hawthorne, who wrote almost 200 years after the Puritans arrived. Hawthorne (1804-1864) was neither a contemporary of the Puritans nor an historian of their era.