Life in Shanghai’s Lockdown

For over two months, fear and insecurity dominated China’s most populous city.

By Blake Stone-Banks

“Shanghai Has No Plans for City Lockdown” read the headline of an article in China Daily, an English-language newspaper owned by the Chinese Communist Party, on March 24, four days before the start of what became the largest citywide lockdown in human history. Quoting health authorities, the article cheered on China’s financial metropolis, which reported just 981 Covid infections the previous day, almost all asymptomatic. The headline provided comfort to those in Shanghai like my family, who had been nervous about rumors of an impending lockdown similar to that in the northern city of Changchun, where residents had been complaining about food and water shortages on social media.

At the time, my family and our entire one-thousand-resident compound were already completing a ten-day, enforced home quarantine due to reported Covid close contacts among residents. We were locked inside our apartment, allowed downstairs once every other day to line up in the parking lot for PCR testing. For some reason, the PCR tests were always after 9:00 p.m., which was frustrating given that our two-year-old twin boys were also forced to attend. It was an inconvenience, but not anything we worried about. Though we understood that the central government took its Zero-Covid policy seriously, we had no inkling of what was to come.

On March 26, two days after the China Daily headline, our social media feeds were filled with reports that military and central leadership were arriving to take over Covid management from the city. Though Shanghai denied this, the lockdown rumors were looking more believable than official sources. The next day, Shanghai announced that Pudong, the district of the city that lies east of the Huangpu River, would lock down for four days, followed by another four-day lockdown for Puxi, the city center that lies west of the river. Living in Puxi, my family was among the lucky ones. Those in Pudong who had trusted the headlines did not even have time to buy groceries.

The total lockdown of Shanghai lasted far longer than four days, extending for nearly two months. It brought fear into the lives of my family that I had never imagined in the two decades that I have been living in China.

Getting to Lockdown

I moved to Shanghai from the U.S. in 2000, the dawn of a century many promised would belong to China. Over the last two decades, Shanghai fulfilled every bit of that promise with internationalism, fast-paced innovation, and an unstoppable economy. Expatriates like myself who call Shanghai home have long looked past the inconveniences of internet censorship and surveillance to relish the city’s stunning architecture, verdant parks, and vivid sense of China’s rich past juxtaposed with its science-fiction future. I live in Shanghai with my wife Wei, a Chinese citizen, and our two children. Until the lockdown, we always felt safer and more at home in Shanghai than in America.

That changed on April 1, the date Shanghai’s Pudong district was supposed to end its lockdown. Though Shanghai officials announced Pudong was ending its lockdown, there was a significant caveat: this was only for sub-districts with zero Covid cases, and there were no sub-districts with zero Covid cases. With the rest of Shanghai now in lockdown, no one was free, and no one had any idea when it might end.

In those first days of hard lockdown, fear seized us when we began hearing reports of young children, sometimes just weeks old, being separated from their parents. We watched videos shared by hospital workers and uploaded onto Chinese social media that showed child quarantines where sobbing toddlers were crowded onto gurneys and beds. Then came videos of the separations—parents physically restrained from babies swaddled in PPE or anonymous toddlers in oversized white suits marched off into vans.

Raising two-year-old twins, my wife and I faced the real prospect of having our children taken from us into quarantine facilities with no way to contact them. We deliberately began sharing cups and utensils with our kids with the hope that if one of us contracted Covid, we would all test positive and avoid family separation. We made plans to bar our door if we tested positive and kept a list of emergency numbers, including that of the U.S. Consulate in Shanghai, which would soon order non-emergency employees to depart China.

We also began hearing reports of more compounds in both Pudong and Puxi where residents were unable to receive food deliveries. I began calling colleagues and friends to check in on them, and I discovered, to my horror, how lucky our family was to live in a large, centrally located compound. Several of them who lived in smaller compounds were struggling to get food. The logistical nightmare of a 25-million-person lockdown was already coming into focus.

Getting Fed

Under normal conditions in Shanghai, you can get anything delivered in under an hour. Even during the localized lockdowns and grid testing that preceded the full citywide lockdown, food deliveries operated without issue. Once the entire city locked down, however, grocery and delivery services had to operate with far fewer staff approved as essential workers to meet the needs of 25 million people, all of whom now needed everything delivered. In practice, this meant that vendors would offer “essential sets,” boxes sold in bulk (typically a minimum order of thirty to forty boxes per order) and filled with necessities like vegetables and rice. If residents fulfilled enough orders, these would be delivered within a couple of days. If the order quota wasn’t reached, all orders would be canceled.

Most of these orders were submitted via WeChat, the social app that serves as the operating system for digital life in China. In addition to its vast number of e-commerce functions, WeChat differs from most international social media in that it is a private channel, which means that posting and messaging are limited to small private groups. During the lockdown, everyone who wanted to eat had to join multiple private WeChat groups to organize group buys of essential sets. Someone in the group would share a WeChat link for the group buy—whether for bags of rice or for KFC. If the compound collected enough orders, the order would be fulfilled.

Smaller compounds had difficulty hitting these purchase targets before they sold out. Though some grocers permitted individual orders, these typically sold out in a matter of seconds, dominated by bots rather than the thumbs of hungry humans. Residents trapped in smaller compounds often struggled to get food and had no idea when there would be a solution.

To complicate matters, group buys had to be approved by one’s “neighborhood committee” (juweihui) as “essential.” Then when the order arrived, the neighborhood committee would coordinate with compound staff to take the food delivery to the resident’s door.

One of my colleagues, who had extreme difficulty feeding his family, including his young daughter, was successful in arranging food deliveries, but the food rotted outside his compound because there was no one authorized to take it from the compound gate to his door. After two days with nothing to eat, he escaped his compound and entered the neighborhood committee office, where he found significant quantities of food and managed to work out “an arrangement.”

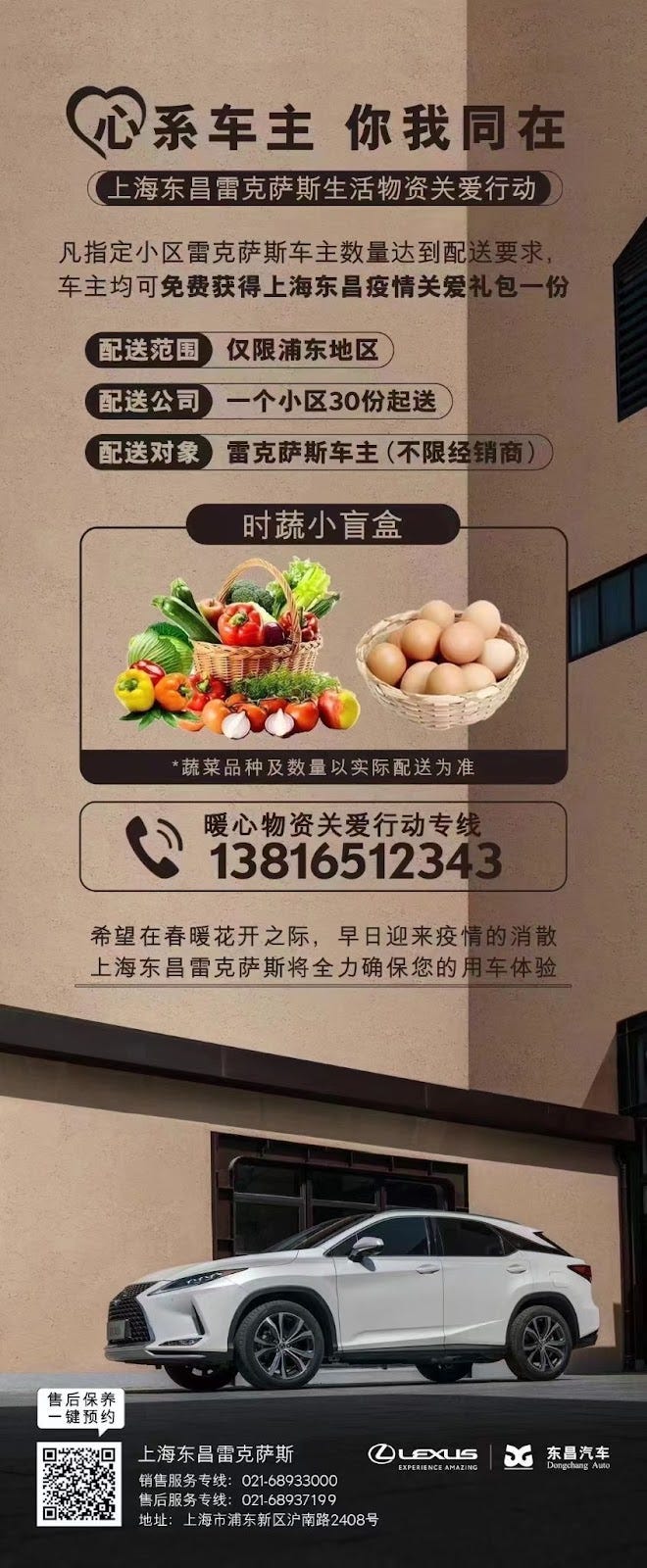

While colleagues and friends were going hungry in smaller compounds, residents in my compound were complaining their refrigerators weren’t big enough to hold all their food. Our compound even arranged “essential” group buys of La Mer cosmetics, though I heard whispers that they paid off the neighborhood committee to get these approved as “essential.” Meanwhile, on WeChat, premium brands like Lexus were offering coordinated grocery deliveries to those in their members clubs. It was odd to see advertisements with a Lexus next to a basket of eggs, but a lot of things were odd during lockdown life.

The media gave much attention to the promised government handouts, but these were far from sufficient. Our family received one duck in an airlocked bag and a few over-ripe vegetables during the first month of lockdown. If we had been expected to survive on the handouts, we would have starved.

That very real fear of starvation soon triggered protests at compounds across Shanghai.

Getting Fed Up

Each morning during lockdown, my wife and I would check the previous day’s Covid numbers on WeChat. Before mass citywide testing began, numbers were in the hundreds each day. Throughout April, confirmed cases were consistently over 20,000 per day. Weeks into a lockdown intended only to last four days, there were no signs of things improving. There was no indication of when we would be able to walk downstairs for sunlight or fresh air. Especially for friends struggling with food, hopelessness and paranoia were taking hold.

Videos in our WeChat feeds provided no comfort: food riots in Songjiang district, police evicting residents to convert their apartments into state-run quarantine centers, suicides of overworked compound staff wearing PPE, and police kicking in doors to compel families into quarantine.

We knew a few people who ended up in state-run quarantines that were often improvised from convention centers and warehouses. Even for those fortunate enough to get a center protected from the weather, these makeshift shelters were typically vast open spaces with hundreds to thousands of beds and bright lights on 24/7. Everyone was referred to by a number; no one had privacy; sanitation facilities were lacking; no one got much sleep.

Our WeChat feeds were filled with videos of protests in the quarantines as well. However, these videos were always quickly censored, often disappearing within seconds of being shared. It became difficult to follow group conversations on WeChat because we often couldn’t see the video being discussed, which had been shared just a few seconds before.

On April 22, Shanghai briefly overcame the censors when a video titled “Voices of April” was shared over WeChat. The video overdubbed black-and-white drone videography of an empty Shanghai with audio clips from the news alongside harrowing conversations between Shanghai residents and authorities. Though this video too was quickly blocked, people refused to stop sharing it, reversing the image, altering the color and length, turning the video upside down—anything to keep the algorithms from deleting it. For an hour, our WeChat feed was nothing but reposts of the video.

Though the next day the video was nowhere to be found on the Chinese internet, it was the first day that my friends in Beijing and other Chinese cities started asking me what was really happening in Shanghai.

Stop Making Sense

Nothing made much sense about how the lockdown was implemented, and we had nowhere to turn for answers. In the first month of lockdown, almost no one could leave their apartment for access to healthcare. Of the three times I am aware someone in our compound called an ambulance, each time the ambulance was denied. There is no official toll of those who died due to Covid hospital restrictions, but many stories were shared on WeChat, including that of a nurse who died from asthma after being refused access to her own hospital. Every time one of our kids bumped his head or choked on his food, we immediately entered triage mode because the ambulances weren’t getting through.

Meanwhile, many in Shanghai, the elderly in particular, remained unvaccinated. Though the city was coordinating daily mass PCR testing and spraying disinfectant in every direction, vaccines were almost nowhere to be found. Then several weeks into lockdown, a new policy was announced that a single positive PCR test could result in entire floors—and in many cases entire buildings—taken into state quarantine, where all were almost guaranteed to contract Covid.

Because these policies seemed so absurd and no one had access to reliable information, there were constant rumors about the intentions behind the lockdown and what was coming next. Many insisted it wasn’t about Covid but about control. Some said it was fallout from a political struggle or rehearsal for martial law. We tried not to listen to the conspiracies and rumors. They didn’t explain the absurdity of denying hospital care with the goal of saving lives any more than they explained the greater absurdity of locking 25 million people inside.

The New Outside

On June 1, my family and I, along with most of Shanghai, were allowed outside again. The city had set up more than 15,000 PCR testing sites, where residents now go for PCR tests in order to receive green codes on our smartphones—digital permission slips to re-enter this former global metropolis turned ghost town.

It should give us hope that our lives in Shanghai will soon return to what they were, but it doesn’t. Lockdowns are extending to other cities. The vast majority of our expatriate friends have left China for good. On their way out, they share photos of a vacant Pudong airport with a single flight on the board. They tweet that this is not how they wanted to leave the city they’ve called home for so long.

Most of our friends staying are like us, Chinese-international couples with children. It’s almost impossible for us to leave right now. To do so, we would need to apply for an entry-exit permit for our children in Pudong, and most families we know have been denied permission to even apply in recent weeks.

Last year, China stopped issuing passports to Chinese citizens for non-essential travel. Then, on May 12, the National Immigration Administration further limited non-essential travel even for those Chinese citizens still holding passports. The following week, a friend of mine called the Public Security Bureau to ask if an exception could be made for her to apply for a passport as her husband, a UK citizen, intended to move back to the UK. They told her “no exceptions” and hung up.

Though we’re free to roam its streets again, Shanghai feels little like the metropolis that captured my imagination two decades ago. There is the lingering fear that new cases could send us off to quarantine or trigger another lockdown. But there is a deeper fear that China’s most international city is closing off to the rest of the world and to the future we had imagined here.

Blake Stone-Banks is an expatriate in Shanghai.

Follow Persuasion on Twitter, LinkedIn, and YouTube to keep up with our latest articles, podcasts, and events, as well as updates from excellent writers across our network.

My thinking is that when they claimed COVID-19 came from a wet market, they were hiding that it was a lab mistake. Now that they are admitting it was likely a lab mistake, I think they are hiding that it was released purposely. https://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-10930501/WHO-chief-believes-Covid-DID-leak-Wuhan-lab-catastrophic-accident-2019.html