Mind the Gap

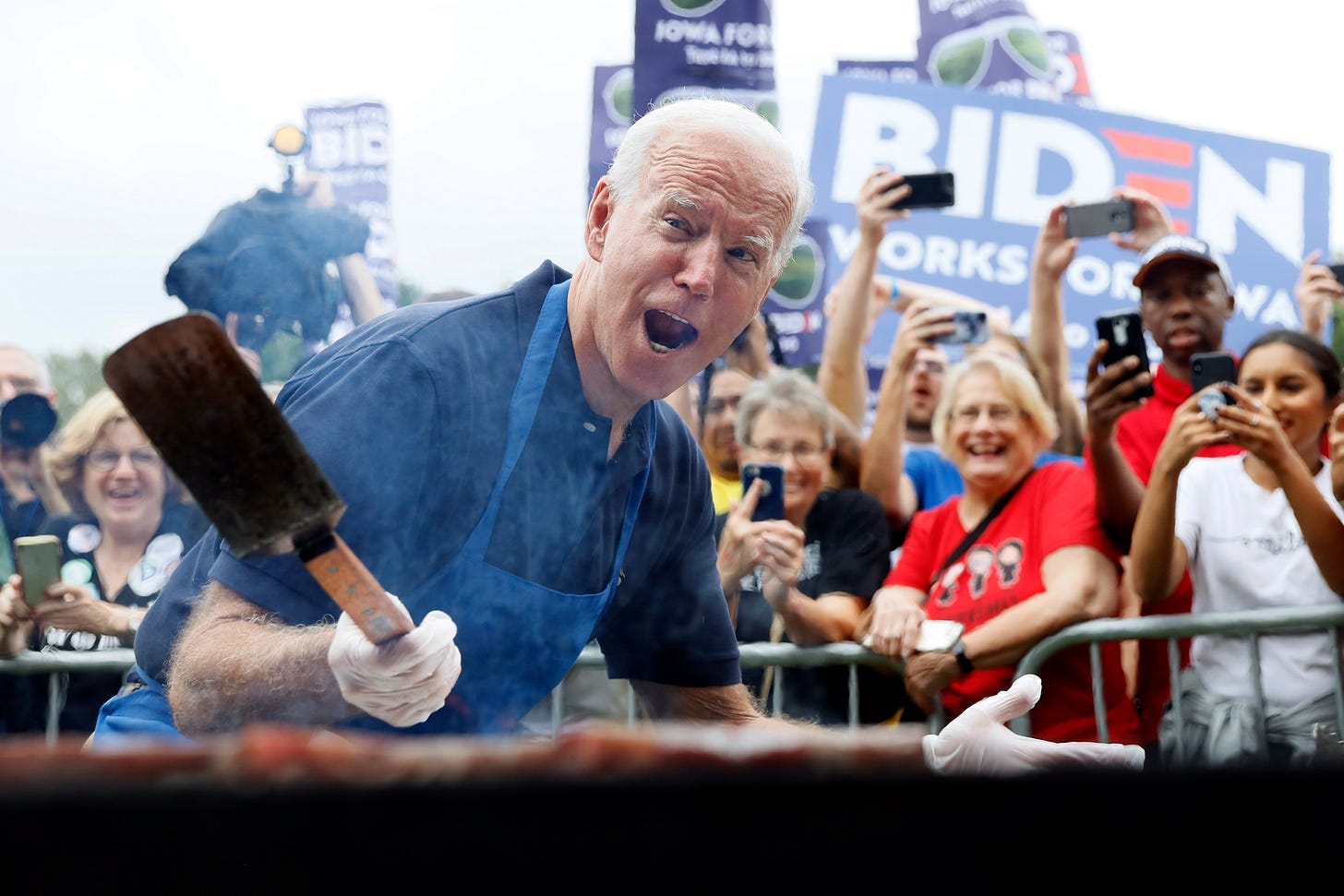

What politicians cook up isn't necessarily what people want. This "representation gap" is threatening American democracy.

Despite Donald Trump’s incompetence, corruption and constant lying, he received over 47% of the votes. The Democratic Party did not win the Senate, lost ground in the House, and underperformed at the state level. Moderates blamed progressives’ attempts to move left; progressives blamed moderates’ desire to tack to the center. But both missed the underlying problem.

A disconnect exists between the preferences of voters and the stances of the Democratic Party on social and cultural issues, while an equivalent chasm exists for Republicans on economic matters. Both are facing what political scientists call a “representation gap.”

A majority of voters, including many Republicans, support Democratic, even progressive, positions on economic issues including tax policy, healthcare, education, the minimum wage and more. But on crucial non-economic issues, voters are moderate, and the Democratic Party’s stances—in particular those of its progressive activists regarding illegal immigration and border security, police reform, “political correctness,” gender identity, sexual harassment and affirmative action—are unpopular, even among many Democratic voters.

There are four common responses to a representation gap:

1) Avoidance. Here, the political party doesn’t change positions, but avoids focusing on issues where there is a gap. Instead, it diverts attention to other matters. This strategy has long been employed by the Republican Party, and was put into hyperdrive by Trump.

Republicans have consistently worked to cut taxes on corporations and the wealthy, even though 60% of voters and 53% of Republicans reject tax cuts for the corporations, and 70% of voters and 54% of Republicans favor higher taxes on the wealthy. Republican tax policies are so unpopular that when pollsters have explained GOP tax bills to voters, they simply “refused to believe that they were describing the bills accurately” because they were so extreme. The same is true on healthcare: When pollsters told voters what Trump and the GOP were trying to do to the Affordable Care Act, they simply did not believe it. As one voter put it, “Nobody would actually vote” for a politician advocating such policies.

Since key GOP economic policies are so unpopular, Republican politicians change the subject, whipping up fears about immigrants, fanning resentment against minorities and liberal elites, and exploiting concerns about changing cultural norms.

As the Republican Party has shown, an avoidance strategy can work. But it carries downsides. The party must keep voters from recognizing that it is implementing policies at odds with their interests and preferences. This creates incentives to engage in ever more extreme distraction.

The avoidance strategy can also undermine faith in democracy itself since politicians and governments are supposed to be broadly responsive to “the will of the people.” When they are not, anger at unrepresentative elites, “the establishment,” and government in general often result—a corrosive dynamic already prevalent in the United States.

2) Intransigence. Here, the political party openly focuses on its unpopular policies, casting them in moral-absolutist terms. This is based on a Manichean view of politics where voters are either friends or foes, and compromise is anathema.

Intransigence keeps an already committed base riled up and mobilized, but it carries significant downsides. Most obviously, it does not prioritize constructing majorities or winning elections. It also undermines democracy since, rather than openly grappling with the unpopularity of policies, it views this unpopularity as a sign of the majority’s ignorance or immorality—a stance that can easily lead to denigration of “the people” or of democracy itself.

3) Concession. In this strategy, the political party abandons unpopular positions, and replaces them with ones closer to voters’ preferences. This follows the view that the party needs to appeal to voters where they are, not where politicians wish them to be.

The attractiveness of this strategy lies in its pragmatism: It prioritizes winning elections. The downside is that it limits the politically possible, assuming that politicians and parties cannot change voters’ minds. For those who believe in the need for significant change, this strategy is dispiriting.

4) Persuasion. Here, the party attempts to close the representation gap by trying to move voters closer to its policies. Changing people’s preferences requires openly grappling with the unpopularity of particular policies, and engaging with those who disagree, rather than disparaging or ignoring them.

Successful engagement means avoiding language and behavior that can be easily misunderstood or trigger fears in voters, and can be exploited by opponents. Progressive activists erred by ignoring this, with some describing themselves as “socialists,” embracing the slogan “defund the police,” and failing to denounce looting and violence that accompanied some protests—behavior that scared some voters away from the Democratic Party. Above all, the persuasion strategy requires patience since shifting voters’ preferences and priorities takes time.

One disadvantage of the persuasion strategy is obvious: It is the most difficult. But its advantages are great. It is the only strategy that reconciles idealism with realism, joining a commitment to currently unpopular but prized policies with a recognition that realizing such policies first requires winning elections.

Those dedicated to nullifying the threat of Trumpism to American society must look beyond this past presidential election. They must win presidential, congressional and state-level elections for years to come. To do this, Democrats—and those Republicans with the courage to disassociate themselves from Trump—need to move past current debates at the extremes of each party, and deal with the underlying problem of the representation gap.

Dissident Republicans face the daunting challenge of convincing their party that its current avoidance strategy, using divisive cultural and racial appeals to distract from unpopular economic policies, is weakening democracy. It is also politically unnecessary since they can win elections without adopting extreme positions on these issues.

Within the Democratic Party, moderates have dealt with the representation gap through the concession strategy, while progressives favored intransigence. But intransigence deepens political divides, while concession leaves moderates unable to attract disenchanted citizens longing for inspiration from their representatives.

The persuasion strategy, on the other hand, offers a way of reconciling progressives and moderates, and strengthening democracy in the process. To progressives, it offers an opportunity to shift the party to the left on issues they care about—but only if they convince a majority of voters, thereby satisfying the moderates’ insistence on winning elections.

For America itself, ensuring that voters actually favor the policies that the two major parties pursue has a major and meaningful benefit: Resentment of “the establishment” will decline, and satisfaction in democracy will grow.

Sheri Berman, a member of the Persuasion advisory board, is a professor of political science at Barnard College, Columbia University. Her most recent book is Democracy and Dictatorship in Europe: From the Ancien Régime to the Present Day.

Thanks so much for a wonderful, down-to-earth essay that looks at the big picture in a practical way. The four types of response to the "representation gap" provide an excellent framework.

If I’ve read him correctly, I believe historian Sean Wilentz has a somewhat different evaluation of the most effective strategy, and it can be explained very nicely within this framework. He suggests different, but equally important, roles for the party and the movement.

To put it simply, we need good politicians to implement the best policies that are currently politically feasible. And we need the movement to change public opinion in a progressive direction. In terms of your framework, the politicians need to be strategic compromisers, while the movement is needed to persuade the voters.

This sharing of roles is more effective for several reasons. (1) Politicians are not burdened with the risky business of explaining to the public why they shoud change their minds. (2) Research on politicians trying to persuade − the bully-pulpit effect -- shows it almost never works and often backfires. (3) The movement can easily take positions that are ahead of the curve (often too easily, so it must be cautious). In fact, persuading is its sole purpose. Hey, that’s us! The persuasion community.

Think of LBJ and MLK. MLK led the movement and persuaded. Had he been the politician trying to hold office, he could not have done his part of the job. LBJ was behind the curve, but a fabulous strategic deal-maker. Together they accomplished great things.

The same relationship held for Teddy Roosevelt and the progressive movement, while he was president. (See Doris Kearns Goodwin’s The Bully Pulpit (a catchy but misleading title)). And something similar was true for FDR − the quintessential compromising politician who followed the lead of movement organizers like Huey Long (far and away more powerful than the socialists and communists).

Suggesting that the politicians should be the persuaders, opens the door for the Sanders’ movement. He literally spoke of using Air Force One to fly around the country and persuade everyone of his democratic socialism. Robert Reich argued that this was the reason to vote for him rather than Clinton. But, as poli-scientist George Edwards shows in “On Deaf Ears: The Limits of the Bully Pulpit,” this would almost surely backfire. And we know it would.

Reich and Edwards are explained here: https://zfacts.com/ripped-apart/left-myths/bully-pulpit/

Under the persuasion strategy, you mention that “progressive activists erred,” but you don’t mention them under the intransigence strategy. In the conclusion, you say “progressives favored intransigence.” I think this signals that the progressive activists believe (and convince many) that they are the persuaders, but their psychology prevents this and makes them intransigent.

I think the Wilentz approach suggests that they should get out of politics, learn to persuade, and do so by leading an MLK-style movement. I am not optimistic. But it may help if we are clear that persuasion mainly belongs outside the party and intransigence is lethal.

Thanks for this neat primer. The stance of many progressive university students (and university grads) is intransigence on a number of issues, including: defunding police, abolishing prisons (and instituting "community justice" or therapy for crimes at all levels of severity), abolishing standing armies, abolishing single sex facilities of all kinds, and assuring that people are fired from their jobs for voicing disapproval with key elements of the radical-progressive worldview. If these and other demands aren't met, many of my students and some faculty members say that a reasonable response is, yes, to burn "it" down, where "it" can be the US government, the two-party system, or other institutions. If traditional academic disciplines don't foster the aspirations of rad-progressive young adults, then those should also be burned down. As I've written before, this isn't my interpretation of what these students--and some faculty--want. This is a phrase I've heard time and again from students and colleagues. I can report from inside the factory of rad-progressive ideology--not, that is, from a traditional discipline--that students categorically reject the idea of persuasion and the possibility of incremental change it promises. They have no interest in giving reasons for what they want and listening to the real, as opposed to predictably caricatured, concerns of those who disagree. An irony is that these students (and faculty) regard themselves as the tribunes of the poor and marginalized, many of whom of course want nothing to do with the positions these intellectuals want to enact. Of course, this is not a new dilemma for far left reformers, but it always seems vexing and incomprehensible to those reformers.