Misinformation Is Here To Stay (And That’s OK)

Attempting to eliminate incorrect speech will do more harm than good. Here’s what we should do instead.

Many of the things that you believe right now—in this very moment—are utterly wrong.

I can't tell you precisely what those things are, of course, but I can say with near certainty that this statement is true. To understand this uncomfortable reality, all you need is some basic knowledge of history.

At various times throughout the history of humankind, our most brilliant scientists and philosophers believed many things most eight-year-olds now know to be false: the earth was flat, the sun revolved around the earth, smoking cigarettes was good for digestion, humans were not related to apes, the planet was 75,000 years old, or left-handed people were unclean.

Around 100 years ago, doctors still thought bloodletting (that is, using leeches or a lancet to address infections) was useful in curing a patient. Women were still fighting for the right to vote, deemed too emotional and uneducated to participate in democracy, while people with darker skin were widely considered subhuman. The idea that the universe was bigger than the Milky Way was unfathomable, and the fact the earth had tectonic plates that moved beneath our feet was yet to be discovered.

Even much of what we believed 20 years ago is no longer true. We thought, for instance, that diets low in fat and high in carbs were much preferable to diets high in fat and low in carbs. Scientists still thought that different areas of the tongue tasted different things. As a public, we thought mass prescribing opioids for chronic pain was safe and that switching from paper bags to plastic bags in grocery stores would save trees (and thus, the environment).

It is challenging to accept the fact that much of what we believe right now will, in 20, 100, 500, or 1,000 years, seem as absurd as some of the ideas above. But it would take a great deal of arrogance to believe anything else.

And yet, that arrogance persists. In fact, it is one of the most important elements of a greater struggle we are facing in the modern world: how to fight the plethora of "misinformation" now available to the public. Arrogance in what we believe now is precisely what creates confidence that we can accurately and productively root out misinformation.

To start, it is worth defining “misinformation”: Simply put, misinformation is “incorrect or misleading information.” This is slightly different from “disinformation,” which is “false information deliberately and often covertly spread (by the planting of rumors) in order to influence public opinion or obscure the truth.” The notable difference is that disinformation is always deliberate.

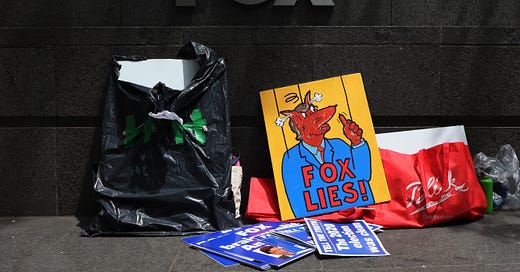

In recent memory, we’ve seen attempts to address the spread of misinformation take various forms. President Joe Biden recently established, then quickly disbanded, the Disinformation Governance Board, a Department of Homeland Security project designed to counter “misinformation related to homeland security, focused specifically on irregular migration and Russia,” according to Politico. Social media companies and creator platforms like YouTube have attempted to root out “Covid-19 misinformation” from their ranks. More infamously, during the 2020 election, Twitter and Facebook both throttled the sharing of a salacious story by the New York Post about a laptop Hunter Biden left at a repair store that was filled with incriminating texts and images on the ground that it was hacked material or a Russian disinformation campaign. As it turned out, the story was true as the Post had reported it.

All of these approaches tend to be built on an assumption that misinformation is something that can and should be censored. On the contrary, misinformation is a troubling but necessary part of our political discourse. Attempts to eliminate it carry far greater risks than attempts to navigate it, and trying to weed out what some committee or authority considers "misinformation" would almost certainly restrict our continued understanding of the world around us.

It's hard to overstate the risks of trying to root out misinformation from public discourse. Imagine, for hypothetical purposes, that the National Academy of Sciences still believed bloodletting was useful to fight infections. Now imagine the government coordinated with major social media platforms to identify and remove anyone questioning the efficacy of bloodletting. Where would we be today? How would we escape the practice? With no dissent, how many people would have to suffer from a lack of effective treatment for us to learn we were wrong?

This idea hardly needs a hypothetical. Two years ago, the greatest health crisis of our time was unfolding, and many scientists believed—with high degrees of confidence—that vaccines prevented the spread of Covid-19 and that the virus started in a wet market in China. These hypotheses were founded in enough science that challenges to them were called conspiracies, and many people were banned from major social media platforms for questioning or outright denying the underlying science.

Today, just two years later, we are confident that vaccines substantially reduce the risk of dying from Covid-19 but we also believe they merely slow, not stop, the spread of Covid-19. The question of where the virus started is now an open debate.

Yet, when these ideas were initially floated at the beginning of the pandemic, many on the left insisted they be removed from public view via de-platforming and censorship. They were, in a synchronous manner, deemed off-limits on Twitter, YouTube, Facebook, and other platforms. This behavior from major corporations, often led by highly-educated liberals, should not be surprising. We know that people on the left tend to attain higher educational degrees. For better or worse, this usually gives them a greater trust in science, scientific institutions, and government entities that act on science-based public policy. As such, the left has become deeply attached to the idea that misinformation that seems to conflict with the scientific consensus must be contained and rooted out.

In an era where hundreds of thousands of Americans died from a virus for which a fairly effective vaccine exists, it's not hard to understand why some would want to enforce science with the help of the law or the weight of corporate behemoths. But apart from being deeply undemocratic, the desire for major corporations or government entities to root out misinformation—even the pernicious "anti-science" kind—is itself profoundly anti-scientific.

It’s worth reiterating precisely why: The very premise of science is to create a hypothesis, put that hypothesis up to scrutiny, pit good ideas against bad ones, and continue to test what you think you know over and over and over. That’s how we discovered tectonic plates and germs and key features of the universe. And oftentimes, it’s how we learn from great public experiments, like realizing that maybe paper or reusable bags are preferable to plastic.

"This era of misinformation is different," many would retort. Indeed, the internet, social media, the speed and scale of communications—all of this makes spreading misinformation easier now than ever. And yet, this argument is not new, and when contextualized in history, it loses its teeth. As Jacob Mchangama explained in his book on the history of free speech, it's the same argument people made about the printing press and then the radio. 100 years from now, there will likely be ways to transmit information faster and at a greater scale than anything we can conceive today, and the internet will look like the printing press does now. Simply put, the threat of "misinformation" being spread at scale is not novel or unique to our generation—and trying to slow the advances of information sharing is futile and counter-productive.

And yet, that’s exactly what our country seems to obsess over. And this obsession is not only present on the left. The right, it should be noted, has become increasingly censorious and illiberal in recent years, too. Rather than fighting misinformation, though, they have focused on restricting discussion of race and gender in schools and on punishing any internal criticism of Donald Trump. Neither side seems particularly interested in putting their worldviews up for honest scrutiny anymore.

Removing "bad" content from the places we now seek out information is not the answer, though. A reader of mine once offered an analogy that I think brings to light my preferred solution: Imagine your job is to put out fires (misinformation) in an area where arsonists (people spreading misinformation) are always setting fires. It takes many firefighters to contain the blaze once it is burning, and if there is a lot of dry brush and kindling, the fire spreads quickly.

You have three options:

Continue fighting fires with hordes of firefighters (in this analogy, fact-checkers).

Focus on the arsonists (the people spreading the misinformation) by alerting the town they're the ones starting the fire (banning or labeling them).

Clear the kindling and dry brush (teach people to spot lies, think critically, and ask questions).

Right now, we do a lot of #1. We do a little bit of #2. We do almost none of #3, which is probably the most important and the most difficult. I’d propose three strategies for addressing misinformation by teaching people to ask questions and spot lies.

First, the media needs to change its posture toward things reporters believe to be false. For years, many journalists have taken to the idea that ignoring misinformation is the way to beat it—that addressing it in any way simply “gives oxygen” or “spreads” the fire. But what the press needs is more honest and open-minded coverage of so-called misinformation that allows people to put down their weapons and hear you out. The problem is that when the people who believe something are the only ones talking about it, there are no skeptical voices in the room, and then certain hypotheses never face honest scrutiny.

An approach that I’ve found successful when covering something like the “stolen election” is first addressing common ground or a set of facts you agree with before attempting to discredit a theory as a “conspiracy.” Yes, election fraud does happen. Yes, the 2020 election was unique. Yes, the rules in many states were changed shortly before the election. And then you explain why none of those things convinced you the election was stolen. More often than not, the most contentious and popular kinds of misinformation are formulated with kernels of truth. I’ve found this posture is often a good way for me to break down walls even with people who have very different beliefs.

The second strategy for clearing away the kindling is educating news consumers on media literacy. Organizations like Media Literacy Now are already doing this work, insisting our public education systems teach the next generation how to be responsible consumers of information online. We need more of this type of education. This is not about indoctrination or politics; it’s about teaching kids how to use multiple sources, think critically about who is behind the media in front of them, and consider what ideas are not being represented in what they’re consuming—even in an article like this.

Third, we need to encourage social media companies not to censor or deplatform, but to add valuable context. Rather than be referees, these entities should function more like stadium announcers. We don’t want them calling balls or strikes, but do want them to tell us the basics—the media equivalent of name, number, position, and hometown. Is this a real person? Who do they work for? Are they a paid government entity? A former intelligence officer? A former politician? A representative of state media?

Platforms like Twitter have begun experimenting with such labels, which is a good step. But the company should employ such tactics more broadly and evenly. What we can’t, and shouldn’t do is to operate on the assumption that our understanding of the world today is some almighty “truth.” We can’t subscribe to the idea that burying any contradictions—the so-called misinformation that drowns out that truth—is the route to a better-functioning and more intelligent society. Our history, both ancient and modern, demands a better answer.

Isaac Saul is the founder of Tangle, a politics newsletter that summarizes the best arguments from the right, left and center on the big debates of the day. You can sign up for free here.

Follow Persuasion on Twitter, LinkedIn, and YouTube to keep up with our latest articles, podcasts, and events, as well as updates from excellent writers across our network.

Well done. Regarding the brush-cleaning, I'll add two points:

1. Skepticism as an inclination is more important than critical-thinking skills. If one wants to believe, the tools of disbelief will simply rust; if one wants to doubt, one will develop the tools.

2. Basic number skills *are* tools that we should focus on providing. Read "Innumeracy", "A Mathematician Reads the Newspaper" and others -- there's a whole genre.

Basically you're correct, and what you say is important.

As a minor quibble, I'd say the Covid mRNA vaccines were extremely effective and produced extraordinarily quickly; that they didn't stop the pandemic is attributable to limited supplies, human cupidity, and the remarkable evolutionary adaptability of the virus. And the purported scientific certainty that Covid-19 originated in a wet market has perhaps more to do with journalistic coverage early in the pandemic than a genuine consensus among virologists.