Of Words and Deeds

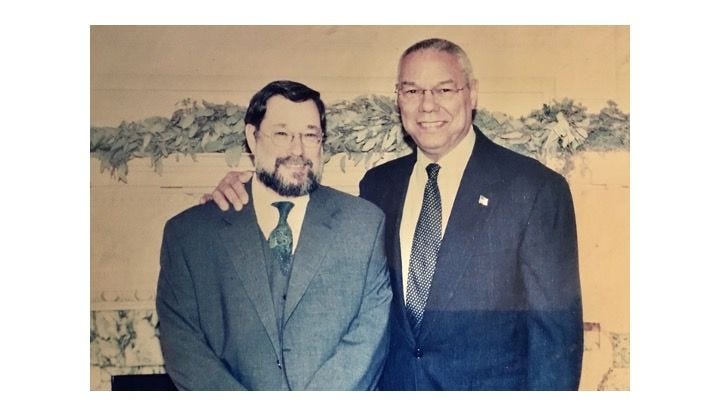

While serving as Colin Powell’s speechwriter at the State Department, Adam Garfinkle learned the distinction more clearly than ever.

This past Wednesday I spoke with Peggy Cifrino, Colin Powell’s longtime administrative assistant, who continued to work for him after he left the State Department in early 2005 at the end of George W. Bush’s first term. Peggy has been a one-woman Jill-of-many-trades ever since, one of her duties being to screen requests and questions from former Powell aides like me. I had a question: Did she think Powell might remember a particular meeting, from April or early May 2004, and if not could she track down the precise date?

That’s when I learned that Powell had been suffering from multiple myeloma, and at age eighty-four was experiencing some memory erosion. “He won’t remember that,” Peggy told me. “The chemo and all, but he’s doing better.”

She asked if I’d been in direct touch lately. “Pretty recently,” I answered. I’d emailed him a link to my June 23 American Purpose essay “Fascinating Rhythm.” I thought it would interest and perhaps entertain him.

He probably read it, Peggy said; his energy waned more as the heat of late summer bore down. Neither of us mentioned Covid, and certainly neither of us expected Powell’s passing just five days later. Of course it saddens me, but I’m sadder still thinking about what Alma must be going through now, after a nearly sixty-year marriage. I strain even to imagine it.

Speechwriting is the form of political writing closest to what a playwright does. I don’t mean that speechwriting is a species of fiction, although it does privilege impression management over the purely didactic. I mean that a speech primarily undergirds and empowers a performative act: the delivery of the speech by a live agent to a live audience. Although scholars and analysts later pour over the speeches of Presidents and cabinet officials, their maiden voyages are exercises in oral, not written, language. As with the performance of a play, the setting and the inevitable interweaving of paralinguistic cues with the script form the whole.

Above all, for a speech to sound naturally oral, any text not wholly memorized must seem to disappear. Powell was a master at this magic, using his hands, face, and especially his eyes to make whatever lay upon a given tilted dais invisible to the audience. But to enable that magic the speechwriter must find the cadences that put the speaker into his comfort zone. That means learning to inhabit the speaker’s spirit so as to avoid all stumbles and stammers, and by so doing win the speaker’s confidence. That’s why writing speeches for Powell felt like a kind of out-of-body experience, and why Powell must have imagined me being a miniature automaton under his suit somewhere messing with his voice box.

Powell spoke “Army prol.” He had more geopolitical intuition in his little finger than some secretaries of state have had in their entire bodies, but he was not especially comfortable with abstract intellectual language. Like most four-stars, he cared more about reading people and knowing the whereabouts of “stuff” that abraded on reality, and only thereafter about lilting words expressing general policies.

That seems to have been one reason why, after he became secretary of state in January 2001, he did not make the standard “pillar” speech a new secretary is expected to make. As Richard Haass, Powell’s first Policy Planning director, later told me, he was out of phase with some of the speechwriters, one of whom, for example, had a University of Chicago history Ph.D.—and, not unreasonably, wrote like one.

A bit past halfway though George W. Bush’s first term, after the simmering second-order differences among administration principals had assumed a particularly bitter shape in the post-combat phase of the Iraq War, and after Powell’s famous February 5, 2002, presentation to the UN Security Council began to show signs of inadvertent accuracy decay, he decided to give a belated pillar speech. For that and other purposes he wanted a new speechwriter, which turned out to be me.

I didn’t speak Army prol, but I was fluent in first-gen American-Jewish prol. Counting spouses, I had thirty uncles and aunts living mainly in the Washington, D.C., area where I was born. So I grew up surrounded by mostly intelligent people, not a one of which—as with my parents—had a college degree. That linguistic immersion proved close enough, as it turned out, for government work. Powell’s pillar speech, delivered at George Washington University’s Lisner Auditorium on September 5, 2003—later redacted into a lead Foreign Affairs essay under the title “A Strategy of Partnerships”—worked pretty well as far as Powell (and not only Powell) was concerned.

We shared another bond we had no need to voice. I grew up in a segregated Old Dominion, and Powell knew it. He grew up in Harlem, but page seventy-two of his 1995 biography My American Journey captures Virginia à la 1962:

Alma and I packed everything we owned … and headed for Fort Bragg.… Driving through Dixie with a new wife was more unnerving for me than the trip a few years before with a couple of Army buddies. I remember passing Woodbridge, Virginia, and not finding even a gas station bathroom that we were allowed to use. I had to pull off the road so that we could relieve ourselves in the woods.

From the windows on the seventh floor of the State Department you can see across the Potomac into Virginia. From the Policy Planning suite in room 7311, Custis-Lee Mansion and parts of Arlington National Cemetery form a scene of historical motion that flows through your soul, if you take time to really see it. Powell and I did not see precisely the same things when we looked out the window, but we did share a tacit understanding of what a difference forty years of American life had made, and it subtly boosted morale in parlous times. In each our own way, our lives had rendered us connoisseurs of loving the imperfect.

Colin Powell taught me much by way of example about leadership, kindness, patience, loyalty, humility, stamina, and service above self. He also taught me something about how national security policy actually happens. Here is how he did it.

When I first walked into Secretary Powell’s inner office to discuss that Lisner Auditorium speech one-on-one, I began, “OK, sir: What, in essence, do you want to say?” A fairly harmless kick-off sentence, I thought. He rolled his eyes back slightly, put his right hand on my left shoulder, and then bored his eyes into mine, replying, “Adam, never ask me what I want to say. Ask me what I want to do. Ask me what this speech seeks to achieve, and I’ll tell you. I hired you to figure out how to say it.”

That’s when I learned the difference between what armchair strategists think they’re doing, and what real professionals know they must do. Luckily, I haven’t been quite the same since.

Adam Garfinkle is an editorial board member of American Purpose and founding editor of The American Interest.