On the Frontlines of Ukraine's Cultural War

A new exhibition of Ukrainian artwork conveys hope, fragility, and rage in a time of war.

American efforts to help Ukraine have largely focused on military and financial support, and understandably so. But as Western news outlets have largely kept their focus on military matters, Vladimir Putin has also pursued an insidious strategy off the battlefield: attacking Ukraine’s cultural identity.

Heartrending destruction has been visited upon Ukraine’s museums, places of worship, memorials, and historical buildings over the last year. UNESCO has verified 240 cultural sites as having been destroyed or damaged by Russian attacks since the invasion began. (The Ukrainian government puts the tally at more than double that.) The government also reports that nearly 40 Ukrainian museums have been looted by Russian soldiers, with tens of thousands of artifacts now lost and still others burned, shattered, or torn apart.

This cultural destruction is sometimes accompanied by terrible loss of life. When Russian precision airstrikes struck the dome of a theatrical stage in Mariupol, it reduced the building to rubble and killed an estimated 600 civilians who had sought shelter in the theater. One survivor said that because no one dug out the bodies of the victims, the theater became “one big mass grave.”

To strike at the heart of a country, attack its culture. In the words of First Lady Olena Zelenska, “This is a war against our identity.” Putin’s now-infamous essay published in the months before the 2022 invasion, “On the Historical Unity of Russians and Ukrainians,” hinges on the idea that Ukraine draws all aspects of its identity from Russia: its culture, its history, its territory. According to this logic, the very cultural life of Ukraine is a direct assertion of that nation’s sovereignty—and therefore a threat to be targeted.

Putin has every reason to fear Ukraine’s poets, artists, and writers. Culture is where a country’s national character comes into existence, is maintained, is allowed to rest and be renewed. It is a source of resilience. Whether it’s materially intangible in the way of a song or poem, or a place that can be visited and studied, like a historic building, these are sites of communal memory; they are capable of strengthening a population in times of hardship and sorrow by offering a common history and shared purpose.

Unfortunately for Russia, its attacks on Ukrainian culture have been counterproductive. Like kicking a dandelion, the brutality unleashed on the Ukrainian people has scattered the seeds of their purposeful creativity around the world. Contemporary Ukrainian artists are producing work with renewed energy and urgency. In attempting to silence the Ukrainian people, Putin has amplified their voices.

It is possible to visit this battlefield and see firsthand why Putin’s cultural warfare strategy is destined to fail. The exhibition Women at War, which opened last month at the Stanford in Washington Art Gallery in Washington, D.C., brings together the work of leading contemporary women artists working in Ukraine; the pieces relate to the ongoing war and Russian occupation, with some being produced since the beginning of last year’s invasion, and others dating to the period following Russia’s invasion and annexation of Crimea in 2014. (Full disclosure: My colleagues at American Purpose helped bring the exhibition to Washington, but those arrangements were made without my involvement.)

The artists of Women at War bring a full arsenal to the battle over their nation’s culture, making use of media and materials that range from miniature watercolor landscape to textiles to sliced river rock. There is unity in this multiplicity: The exhibition brings to Washington a distinct outlook related to the Ukrainian experience. The artists are victims of Russian aggression, yes, but in their creative reformulations of and responses to that inescapable reality, they offer glimpses of lives that are full of subversive humor, compassion, and courage.

From the perspective of Russia’s goal of cultural destruction, the great danger of this exhibition is how effective it is in conveying the richness and nuance of Ukrainian identity. There are works here that can puncture the protective layer of apathy that many Westerners have put on following a year of unrelentingly grim news coverage.

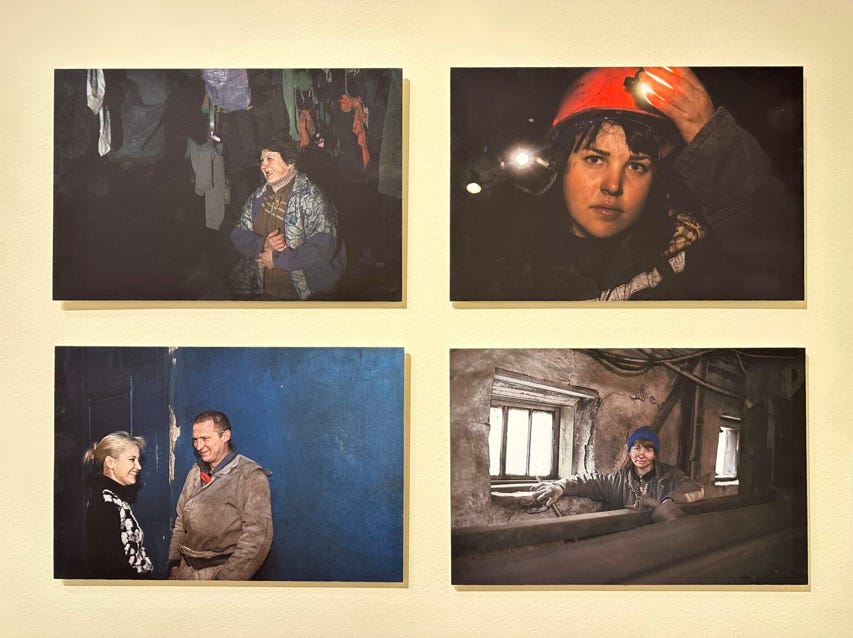

Artist Yevgenia Belorusets spent years photographing the women who worked in the coal mines that skirted war zones in the Donbas. Her subjects, young and old, are helping meet Ukraine’s energy needs to keep the country functioning. As Belorusets notes in the wall text, the work these women are conducting is “a form of resistance to the occupation, which was politically invisible because it took place at workplaces striving to avoid any kind of publicity.” The invisibility of their efforts, while a common characteristic of women’s labor, possesses its own strategic advantage in wartime.

There is one photo in particular that I could not stop returning to (top left in the image above): A short-haired woman in her sixties stands in the coal mine’s dressing room. She grabs at her sleeve as she prepares to change, but it’s hard to know which sleeve, given the variegated layers of sweaters and jackets she is wearing. Each garment has been dulled by grey-brown dust. But her smile, illuminated by the camera flash, is dazzling for the contrast: Gold front teeth glimmer. Rose-red cheeks wrinkle in a timeworn smile. Her moment of joy is real, unguarded, a glimpse of resilience in a bleak scenario like a precious gem in a tarnished setting. Fittingly, the series to which the photo belongs is titled Victories of the Defeated.

Here is a hard-fought joy—but here, too, is a blistering rage. Artist Olia Fedorova was living in Kharkiv in March 2022 when Russian forces began a campaign of shelling the city that went on for months. To continue working under the new conditions, the multidisciplinary artist shifted to new media: whatever materials she could find in the underground bomb shelter. As her native city was destroyed above her, she began composing imprecatory poems on ripped bedsheets and textiles. Tablets of Rage is a series of these compositions, which together convey a sense of dialogue between artist and the faceless Russian soldiers. Her words become her weapon—not only against the aggressors, but against that other great threat, the apathy of Western audiences.

A set of Fedorova’s bedsheets faces visitors at one of the gallery’s main entrances. Lines of red marker twist across the white cloth, forming loops of Cyrillic cursive. These improvised canvases bear curses for the Russian soldiers invading her country. Translated to English, the poem reads:

May you choke on my soil.

May you poison yourself with my air.

May you drown in my waters.

May you burn in my sunlight.

May you stay restless all day and all night long.

And may you be afraid every second.

Her words burn. It is hard to imagine any news coverage that could give a sense for the truth and reality expressed here.

As the siege on Kharkiv wore on, Fedorova took to sharing her prayer-poems on Instagram, each post its own act of defiance but also an offering of comfort to those who saw their emotions reflected in her work. “Once the invasion started, it was clear that there’s no in-between; it’s only: Would you rather die or survive?” Fedorova noted in an interview last fall. She knew she had to practice her art and communicate her experiences in the way she best knew, to “strike people right in the heart.” To her, this is a contribution to the battle to defy Russian acts of erasure.

The exhibition is billed as “a platform for women narrators of history” to explore war through the lens of gender, a well-fitted frame for the daring works of Fedorova and Belorusets. Both artists center their work on wartime resistance and challenge the notion that women noncombatants are passive victims of fate. If we accept Putin’s interpretation of Ukrainian culture as amounting to an attack on Russian sovereignty, then these artists are truly in the trenches.

In a few places, Women at War stumbles on its own conceptual framework. The catalogue and wall panels tend to become academic excurses on historiography and feminism, pulling visitors (myself, at least) away from the immediacy of the art at hand. Russia and Ukraine are preparing their spring offensives as the war grinds into its second year, and the lens of gender studies offers too narrow an aperture to comprehend the scale of what is soon to come.

But at its most touching, the art in this exhibition offers a disarming foil to Putin’s performative masculinity. This is the case with Ukrainian artist Alevtina Kakhidze, whose chronicles of war are characterized by qualities of tenderness and fragility.

Days after visiting the exhibition, my thoughts kept returning to Strawberry Andreevna, Kakhidze’s mother. Ms. Andreevna, called Strawberry, is portrayed in a series of ink drawings chronicling her day-to-day life in occupied Donetsk. The drawings are gently and darkly humorous and have a playful edge. In one, Strawberry wanders around the tombstones of a local cemetery—the only place in town with a decent cell phone signal—while calling her daughter to assure her she is alive.

Snippets of these cemetery phone conversations are then illustrated by Kakhidze, offering intimate views of occupation life. For Strawberry, that life entailed an exhausting journey across the demarcation zone several times a month to collect her pension checks. About half a million retired Ukrainians live in the occupied territories, and they must face these regular trips into non-occupied territory to receive their government support.

Kakhidze depicts this dangerous trek as a long caravan of people walking under a starry sky. Below the ink drawing is a simple sketch of Strawberry holding a plaid bag and narrating: “It took me 11 hours to cross a distance which I crossed before the war in 1.5 hours.” She continues: “Take a look at those pages of propaganda . . . I put them around jars so that is all they good for.” Decorating your pickled preserves with propaganda—a wry bit of guerilla resistance, grandmother style.

The final panel in the series takes a different tone. Black ink has given way to glacial blue. A bus and a flagpole flying the emblem of Russian occupation anchor the background. In the foreground, one small human figure is laying on its side, with other people standing around and clustered nearby. Above the horizontal figure: “MAMA” in black boxed letters. Strawberry’s final panel depicts her cardiac arrest and death as she crossed the demarcation zone.

The artwork of Women at War cannot replace the culture being destroyed by Russia, just as Strawberry Andreevna cannot be brought back through the artwork of her daughter. But these creative acts carry power and significance nonetheless. Russian forces have developed a perverse power to determine the news coverage that we see in the West, largely by conducting campaigns of such destruction and cruelty that reporters cannot look away. Over time, this unrelenting tragedy dulls Western audiences, who develop emotional callouses to help them live without being constantly pierced by the news.

Ukraine’s culture producers, including the artists of Women at War, are expanding on these narratives. They are reframing war as an intensely personal experience, one measured not in campaigns and seasons but in individual moments—ones where women smile as they keep their nation’s lights on by mining coal at the edge of war, or repurpose Russian propaganda to decorate the jars of their preserves. Curator Monika Fabijanska has gathered these moments into an epoch all their own. Her selection of deeply resonant works is grounded in both Ukraine’s terrifying reality and the richness of the human spirit.

Putin seeks to subordinate Ukraine and wipe away its cultural identity. He has given a nation of artists the fuel to produce uniquely powerful expressions of Ukrainian identity instead. These artists may not be combatants, but they are on the front lines of war.

Carolyn Stewart is the managing editor of American Purpose.

This article originally appeared in The Bulwark and has been republished with their permission.

Women at War was curated by Monika Fabijanksa and produced by the Fridman Gallery, New York, in collaboration with Voloshyn Gallery, Kyiv, and will be on view at the Stanford in Washington Art Gallery through March 21, 2023.