Painting Our Principles

During WWII, Norman Rockwell gave color to the “four freedoms” that united Americans. Eighty years later, Rockwell’s canvases deserve a second look.

America’s purposes are very much matters of the mind, and American minds are filled with iconic images that shape our self-understanding, hopes, and goals. There’s Washington crossing the Delaware, the signing of the Declaration of Independence in Independence Hall, Grant Wood’s “American Gothic,” and U.S. Marines raising the flag over Mount Suribachi. There are also harder images—police dogs brutalizing Civil Rights marchers in Alabama, President John F. Kennedy’s car pulling away from the motorcade after he was struck by an assassin’s bullet in Dallas, and the burning World Trade towers on 9/11. And for the generation of wartime and postwar Americans, the iconic images include Norman Rockwell’s 1943 series of “Four Freedoms” paintings.

On Saturday, February 20, 1943—just eighty years ago—as the Axis powers waged total war against the Allies, millions of Americans opened their weekly issue of the Saturday Evening Post and admired a painting by Norman Rockwell titled “Freedom of Speech.” It portrayed one of the four “essential human freedoms” proclaimed by President Franklin D. Roosevelt two years earlier. Subsequent issues of the magazine featured Rockwell paintings that interpreted FDR’s three other freedoms—“Freedom from Fear,” “Freedom to Worship,” and “Freedom from Want.”

Recently, while teaching undergraduate and graduate students, I found that only two of Rockwell’s paintings, “Freedom from Want,” with its portrayal of a family on Thanksgiving, and “Freedom of Speech,” a scene from a town meeting, were even vaguely recognized. Very few students knew the name of the artist; none were aware that the paintings are part of a series. And they certainly did not know that the paintings became the core of an official campaign to define and communicate American purpose in a time of war. There are loud echoes of 1941 in 2023, but today, despite the contemporary rise of dictator states and malicious international actors–not to mention Russia’s launching a new land war in Europe–“The Four Freedoms” do not inhabit the minds of newer generations of Americans.

It’s a loss.

Franklin Roosevelt’s Words

In his State of the Union Address on January 6, 1941, less than a year before the bombing of the American fleet in Pearl Harbor, President Roosevelt asked Congress for authority to provide Lend-Lease assistance to the United Kingdom and “funds sufficient to manufacture additional munitions and war supplies . . . to be turned over to those nations which are now in actual war with aggressor nations.”

With large numbers of Americans at the time wanting no involvement in the war, Roosevelt knew he must explain to Americans, in American terms, why they must prepare for war. When he spoke of “a decent respect for the rights and dignity” of both “our fellow men within our gates” and “all nations, large and small,” he connected the need to support Britain and other nations to longstanding ideals of freedom and inherent rights sacred to Americans. He concluded the address by tracing a vision of “a world founded upon four essential human freedoms,” and detailing the four freedoms:

The first is freedom of speech and expression—everywhere in the world.

The second is freedom of every person to worship God in his own way—everywhere in the world.

The third is freedom from want, which, translated into world terms, means economic understandings which will secure to every nation a healthy peacetime life for its inhabitants—everywhere in the world.

The fourth is freedom from fear, which, translated into world terms, means a world-wide reduction of armaments to such a point and in such a thorough fashion that no nation will be in a position to commit an act of physical aggression against any neighbor—anywhere in the world. [emphases added]

After the President’s address to Congress, his administration repeated the formula in speeches, messaging, and diplomacy. The Atlantic Charter, signed by President Roosevelt and Prime Minister Churchill on August 14, 1941, acknowledged “common principles” as their nations faced “the Hitlerite government of Germany.” They sought a peace when all “may live out their lives in freedom from fear and want.” On the Atlantic Charter’s first anniversary, FDR also spoke of “religious freedom.”

To further circulate the message, in February 1943 the U.S. Postal Service printed nearly 1.3 billion one-cent Four Freedoms stamps. Looking overseas, the Office of War Information (OWI) sponsored the design and circulation of cuatro libertades posters aimed at Latin America.

Despite such efforts, pollster George Gallup told the Roosevelt administration that the Four Freedoms as a rallying narrative “had not registered a very deep imprint here at home.” The OWI was anxious that “FDR’s Four Freedoms theme had turned into an embarrassing flop.”

Norman Rockwell Portrays the Four Freedoms

Meanwhile, wholly separate from such federal efforts, an artist in Vermont known for his magazine and calendar illustrations was possessed by a desire to “take the Four Freedoms out of the noble language and put them in terms everybody can understand.” One sleepless night, the artist—Norman Rockwell—recalled a Vermont neighbor speaking against a popular proposal at a town meeting:

But they had let him have his say. No one had shouted him down. My gosh, I thought, that’s it. There it is. Freedom of Speech. I’ll illustrate the Four Freedoms using my Vermont neighbors as models. I’ll express the ideas in simple, everyday scenes. Freedom of Speech—a New England town meeting. Freedom from Want—a Thanksgiving dinner.

The result was Rockwell’s famous Four Freedoms paintings. His homely approach was to highlight what Americans enjoyed on a daily basis—democracy, safety, faith, and bounty—because they had the Four Freedoms. FDR’s “Four Freedoms” and Rockwell’s paintings were meant to rally Americans and the allies by reminding them of what they stood to lose should totalitarianism and dictatorship triumph.

"Freedom of Speech" showed a workingman speaking at a Vermont town meeting, while his better-off neighbors listened respectfully.

In "Freedom from Fear," a couple looks down on their sleeping children. The headline visible in the father's newspaper tells the story—"bombings" and "terror."

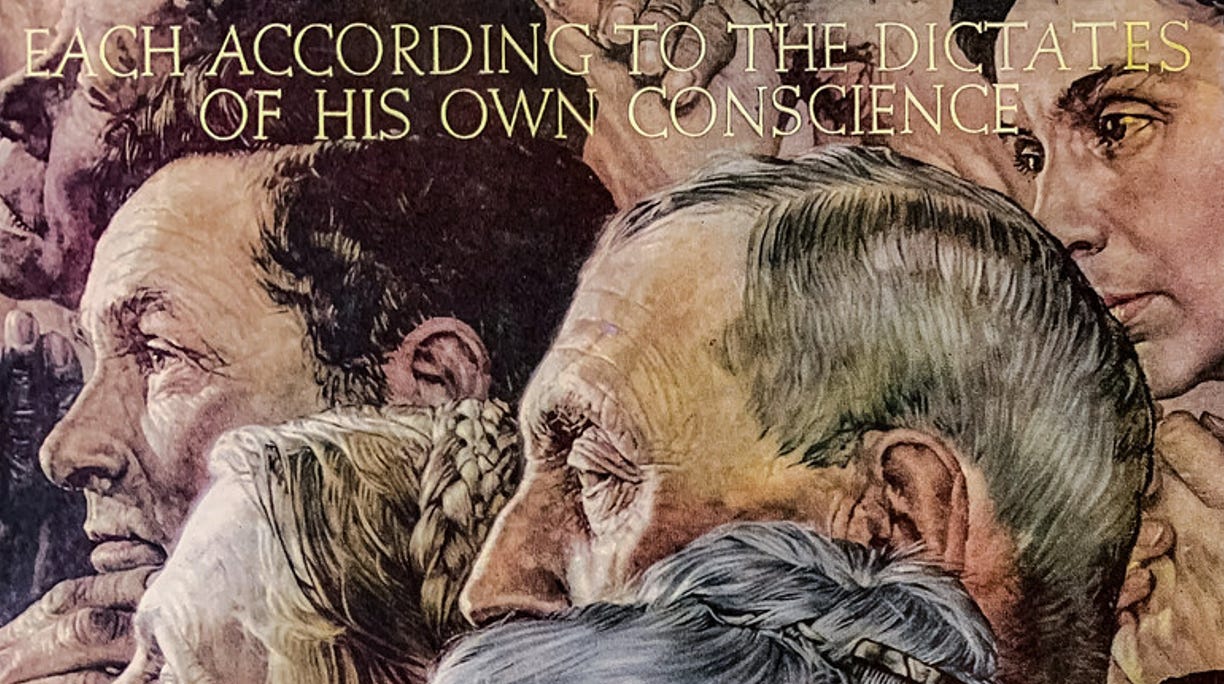

"Freedom of Worship" provided a collage of worshippers. Those in the center of the painting no doubt represented the majority Protestant denominations. The woman on the left, holding a rosary and with a braided crown of hair, is Catholic; perhaps an immigrant. In the lower right, the man wears a songkok, a cap popular in India and Southeast Asia. Significantly, the figure shown partially in the upper left of the painting is a Black American. Previously, portrayals of Blacks in paintings commissioned by the publisher were rare. The magazine’s policy was only to show them in lesser roles—as a child, the “help,” or a Pullman porter, for instance. Here, the figure does double duty—portraying both inclusion and another stream of American Christianity.

"Freedom from Want" depicted an American family celebrating Thanksgiving.

Initially, the wartime agencies showed no interest in Rockwell’s four paintings. The artist accordingly approached the Curtis Publishing Company, which ran them in four consecutive issues of the Saturday Evening Post on February 20, February 27, March 6, and March 13, 1943.

The paintings made publishing history. More than 25,000 readers purchased sets suitable for framing. Rockwell received 60,000 letters offering thanks, reflections, and suggestions. The Treasury Department and the magazine quickly sponsored a Four Freedoms War Bond Show, exhibiting Rockwell’s series around the nation. Each person who bought a war bond received a set of Four Freedoms prints. The campaign raised $130 million—more than $2.2 billion in 2022 dollars.

President Roosevelt’s words and Rockwell’s paintings inspired subsequent speeches, articles, sermons, books, music, and paintings. Roosevelt himself commissioned a related sculpture, which can now be seen in Madison, Florida.

Until the war came, most Americans had primarily been coping with the downhome problems of the Depression. Once the war began, however, the Four Freedoms gave Americans four lenses with which to discern its meaning. Thus Nazi book burnings and executions of opponents clearly violated Freedom of Speech. There was no Freedom from Fear when bombs fell on London and Chungking. When Americans saw newsreels of hungry Chinese refugees, they felt more keenly their own Freedom from Want. And when Nazi persecution of Jews—and later Hitler’s “Final Solution”—became known, Americans knew the meaning of Freedom to Worship.

The War and Beyond

Belatedly realizing the power of Rockwell’s project it had once dismissed, the OWI eventually printed another 2.5 million copies, as well as a pamphlet, “The United Nations fight for the Four Freedoms.” The latter began:

Beyond the war lies the peace. Both sides have sketched the outlines of the new world toward which they strain. The leaders of the Axis countries have published their design for all to read. They promise a world in which the conquered peoples will live out their lives in the service of their masters.

The United Nations, now engaged in a common cause, have also published their design, and have committed certain common aims to writing. . . . The freedoms we are fighting for, we who are free: the freedoms for which the men and women in the concentration camps and prisons and in the dark streets of the subjugated countries wait, are four in number.

In time, the Four Freedoms became shorthand for the Allies’ war aims. After the war, the 16 million Americans who had served in uniform received a Victory Medal; the Four Freedoms were inscribed on its reverse.

In 1948, the United Nations General Assembly proclaimed the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. Its preamble invoked “the advent of a world in which human beings shall enjoy freedom of speech and belief and freedom from fear and want….”

Since then, the Four Freedoms have been honored and celebrated in everything from public charters to public art to political commentary. Many monuments to the Four Freedoms were raised. Evansville, Indiana, for example, is now the “City of the Four Freedoms.” Muralist for the U.S. Capitol Allyn Cox placed Four Freedoms images in the hallways of Congress. And in 2005, the magnificent FDR Four Freedoms Park opened on Roosevelt Island off Manhattan.

Closer to the present, in the pages of Foreign Affairs, G. John Ikenberry has written that the FDR speech “is widely seen as a landmark statement of American foreign policy.” Vasily Gatov of the University of Southern California has additionally written that during the Cold War, the United States’ “‘personality’ was based around the concept of freedom,” and that FDR’s Four Freedoms were the “roots of this freedom narrative.”

Retired Marine Corps General and former Secretary of Defense James Mattis has brought it homefor our times: “I had many privileged glimpses into the human condition, but I never once saw human beings flee the freedom of speech; I never saw families on the run from the free practice of religion in the public square; and as a young Marine, I never picked anybody out of a raft on the ocean desperate to escape a free press.”

A Continuity of American Ideals

For decades, art critics deemed Rockwell as a mere “illustrator,” judging his portrayals of America in decades from the 1920s to the 1950s as sentimental, smug, and sterile. His reputation as an artist, however, is now secured. Perhaps Sotheby’s 2013 sale of another Rockwell painting, “Saying Grace,” for $46 million helped prompt the re-evaluation. Both George Lucas and Steven Spielberg collect Rockwell works.

When Americans stop to consider the iconic images now, they often first notice that the figures shown in the paintings don’t look like the America of today. The paintings appeared before the Civil Rights movement; before the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965 opened the doors to more, and more diverse, immigration; and before most Americans prioritized inclusion and diversity among the nation’s primary characteristics. That said, the appearance of a Black American in Rockwell’s “Freedom of Worship” painting signaled the artist’s own openness to social change, and in the late 1950s and 1960s his series of civil rights paintings helped change American attitudes.

Rockwell’s Four Freedoms can seem to speak only to yesteryear. Yet, the continuity of American ideals represented in the paintings joins, rather than divides, World War II and the present. In Congress and the state legislatures, debates about topics as diverse as speech codes, the defense budget, the role of religion in society, and entitlements continue to be, at root, debates about speech, fear, worship, and want. These values endure.

The Four Freedoms Today

The totalitarian evils addressed by FDR’s Four Freedoms are still recognizable eighty years later. Then, the bombers striking fear into human souls were Heinkels and Bettys. Now, they are Russian fighters and Iranian drones. In 1941, President Roosevelt spoke of “dictator nations” that spread “poisonous propaganda” to “destroy unity and promote discord in nations that are still at peace.” Russia, China, and North Korea are three dictator nations that continue to do so in our present day.

During that conflict, FDR also said that America’s support for democracies under assault was “to act as an arsenal for them as well as for ourselves”—to send, “in ever-increasing numbers, ships, planes, tanks, guns.” Such words arguably resonate today in terms of Russia’s ongoing war in Ukraine.

Air Force Colonel John Boyd, “the fighter pilot who changed the art of war,” once wrote that America needs “a unifying vision,” one that “attracts the uncommitted and magnifies the sprit and strength of its adherents, but also undermines the dedication and determination of any competitors or adversaries.” To my mind there’s no need to invent a new “unifying vision” out of whole cloth. FDR—and Normal Rockwell—have already gifted us one with the Four Freedoms. It’s a legacy that deserves to be passed on to those now assuming America’s leadership.

Donald M. Bishop served 31 years in the U.S. Foreign Service as a public diplomacy officer in Hong Kong, Taiwan, Korea, Capitol Hill, Bangladesh, Nigeria, China, the Pentagon, and Afghanistan. After retirement, he served a term as president of the Public Diplomacy Council. He is now distinguished fellow at the Brute Krulak Center for Innovation and Future Warfare at Marine Corps University in Quantico.