There are many domains in which there is a strong norm of non-partisanship. The classic bureaucrat described by Max Weber is not a partisan, but rather a neutral technocrat whose role lies in expertly carrying out mandates provided by political leaders. Though politics always intrudes at some level, we do not want NASA, or NOAA, or the Federal Reserve to make decisions based primarily on whether it will benefit one political party or the other, nor do we want the trash to be collected only in Democratic rather than Republican neighborhoods (or the reverse). Officials may be elected on a partisan basis, but in their role as governor, city manager, or judge, they are expected drop their partisan personas and act as public servants.

The very definition of a modern state revolves around it being impartial and non-partisan. Indeed, trust in government depends heavily on people’s belief that the state’s machinery is being deployed in the public interest, and not simply to benefit one particular political group.___STEADY_PAYWALL___

Needless to say, the norm of non-partisanship has been severely eroded in recent years. American public health agencies like the CDC or the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases got drawn into a nasty political fight during the Covid pandemic. Even NOAA found itself in the presidential crosshairs for contradicting the White House’s assertion about the path of a hurricane.

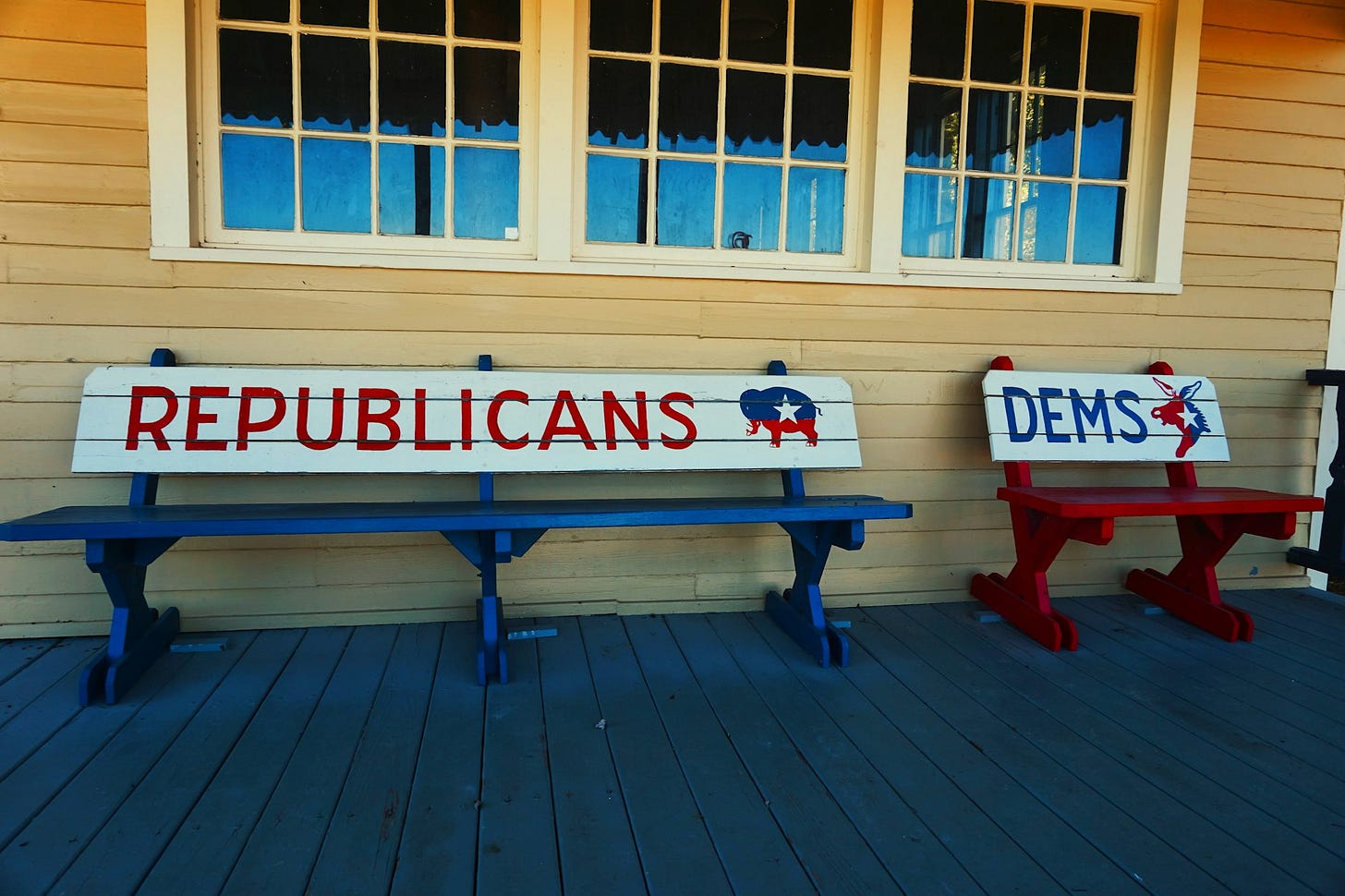

In virtually all other developed democracies, the administration of elections (ranging from redistricting in countries with single-member districts to the counting of votes) is carried out by non-partisan bureaucrats. For deep-seated historical reasons, this function in the United States has been done by instead by the two political parties. Many Europeans looking at this practice cannot believe that we are this primitive, but in actuality the system has worked pretty well up to now because of the strong norm of non-partisanship. There are state-level officers who are elected on a partisan basis, but who in their official administrative capacities behave as impartial bureaucrats. The exemplar of such an official was Georgia’s Brad Raffensperger, who was elected as a pro-Trump Republican, but as State Secretary of Georgia oversaw a clean election and asserted its legitimacy in the face of enormous pressure from Trump and his followers to change the count in the former President’s favor. Today, the norm of non-partisanship is being challenged across the board by Republicans, and nowhere more strongly than in the effort to put overt partisans into positions of power over election administration. Larry Diamond has written in this journal about the systematic campaign to elect 2022 election deniers in Nevada, Pennsylvania, and other states. This is part of a larger trend in conservative politics to contest the impartiality of the bureaucracy as a whole, and to see public officials as part of a “deep state” whose primary loyalty is partisan at its core.

In challenging the legitimacy of the 2020 election, pro-Trump conservatives have crossed a red line into territory that does not simply seek to contest a policy preference within a broadly democratic framework, but seeks to undermine that framework, and therefore American democracy, as a whole. As is being made abundantly clear by the January 6 Congressional Committee, Donald Trump was repeatedly told that there was no serious evidence of fraud in the election, and yet he has subsequently continued to challenge the results and tell his followers that the system is “rigged” and deeply corrupt. A full rebuttal of election fraud charges has been presented by a group of conservatives in their report lostnotstolen.org. By continuing to contest the election’s legitimacy, Trump eats away at the very foundations of the Constitutional system itself, and moves into overtly anti-democratic territory.

This posture then necessarily erodes the norm of non-partisanship on the part of the rest of us, and in a sense forces us to become partisans ourselves. I can illustrate this with reference to two democracy promotion organizations with which I have been affiliated, the National Endowment for Democracy (where I was a board member for 18 years), and Freedom House (on whose board I serve now). Both organizations seek to promote democracy around the world, in part by strengthening the ability of parties to contest democratic elections. Two of the NED’s component institutes, the National Democratic Institute (linked to the Democratic Party) and the International Republican Institute (linked to the Republicans) were established explicitly to work with and strengthen like-minded parties in countries around the world.

None of these organizations support all parties, however: parties that had a non-democratic record, or were suspected of being anti-democratic, were off the list. Thus during the Cold War, they did not work with the French or Italian Communist Parties, and in recent years have stayed clear of groups like the Muslim Brotherhood in Egypt or the AKP in Turkey. Non-partisanship ends, so to speak, at democracy’s edge.

Freedom House has been very vocal in the past few years charting the decline of democratic practice in the United States; the latter’s deterioration is one of the big drivers of its aggregated global democracy measures. On the other hand, it has been silent on issues like the recent Dobbs Supreme Court decision to overturn Roe v. Wade. The latter had provoked great and, for me, justifiable outrage, but the Court’s decision remains squarely within the framework of permissible partisan disagreement and deliberation. One may dislike the fact that SCOTUS has taken a position supported by a minority of Americans, but the decision itself did not constitute an attack on fundamental democratic institutions. Freedom House’s decision to remain silent on this neuralgic domestic issue was therefore justified, as was its decision to speak critically of Republican efforts to overturn the 2020 election.

As the Republican Party moves to endorse Trump’s view of the last election and prepares itself to be able to manipulate the next one, it has left the family of parties operating within a democratic framework. One can contest a wide variety of policies favored by Republicans and Democrats, but not policies designed to deliberately weaken democracy itself.

As a consequence, I believe it is of great importance that the Democrats retain control of Congress and legislatures at a state level in 2022, and that a Democrat wins the 2024 Presidential election. I do not say this out of partisan loyalty, or as a matter of policy preference. The Democrats have been dominated by the activist progressive wing of the party that continues to do its utmost to push away the moderate swing-state voters. President Biden’s abysmal poll numbers demonstrate the degree to which he has been captured by that wing, as well as legitimate concerns about his age, judgment, and vigor. Vice President Harris’ track record does not suggest that her appeal would be any broader than the President’s, or that she will do a better job than him.

The vast majority of Americans believe that we are facing a normal partisan choice today, in which policy preference and judgments about leadership qualities should determine our vote. I wish this were true, but a large part of the Republican Party has evolved in an extremist direction that puts it outside of the realm of acceptable democratic choice. For the first time in my experience, we are facing at home the same dilemmas that democracy promoters have faced abroad in democratically-challenged societies. The issue is not partisanship but democracy itself.