Recalibrating Liberalism

Danielle Allen’s Justice By Means of Democracy provides the road map that contemporary liberalism so desperately needs.

Justice by Means of Democracy

by Danielle Allen (University of Chicago Press, 288 pp., $27.50)

In her recently published Justice by Means of Democracy, Danielle Allen, a professor at Havard University’s Department of Government, offers a compelling and wide-ranging articulation of liberalism. She shows that not only do liberalism and democracy often go together, but also that they are inseparable partners in the quest for human flourishing. In Allen’s view, human freedom is predicated on political equality, which is increasingly under threat as power becomes concentrated among the wealthy.

Throughout history, liberalism’s key scholars have argued that negative liberty—freedom from oppression by the powerful—is the chief goal of liberalism. Allen firmly rejects this premise, suggesting that government protection and restraint mean very little without positive liberty, active efforts on behalf of government to ensure each citizen has some ability to shape his or her life. In this respect, Allen is not so much offering a completely original idea as she is highlighting a strain of the liberal tradition that stretches back to figures such as George Bancroft and Alexis de Tocqueville. In the eyes of these individuals, as for Allen, freedom requires self-government broadly defined. All people–regardless of race, social background, and economic status–should have the means to shape their own lives both culturally and politically.___STEADY_PAYWALL___

Like her intellectual precedessors, Allen bases this central insight about the nature of liberalism upon an account of the purpose of government. That purpose, she argues, is justice, which she defines as “those forms of human interactions and social organization necessary to support human flourishing.” She admits that what exactly constitutes human flourishing is less clear, but, rather than an artful dodge, Allen sees this ambiguity as essential to democratic liberalism. She states this quite plainly in the book’s opening pages: “I think there are better and worse ways for human beings to live . . . but at the same time, I think human beings can figure out how they will best flourish only by putting their heads together.” In short, it is only through a process of democratic deliberation that we can construct a just society in which individuals flourish.

Allen provides a detailed account of what justice by means of democracy requires of citizens. If justice requires democratic participation, this in turn requires a citizenry engaged in politics—the very opposite of the disengaged and self-centered liberal so often lampooned by post-liberal theorists. In a truly liberal democratic society, each and every citizen within the nation has an important part to play in governing, whether as a voter, politician, or activist—and no job takes precedence since each needs the other.

To engage in democratic dialogue also requires what Allen, borrowing from Martin Luther King, Jr., calls “integration,” the idea that we must all learn to live with one another as a single community. Here again Allen challenges post-liberal assumptions, for this pluralism is made possible not by abandoning virtue and forging a society founded upon self-interest, but instead by something much deeper: mutual recognition of the purposiveness of human life. To put it another way, justice by means of democracy demands that citizens appreciate the inherent dignity in each other’s lives—a dignity built on the fact that we are all pursuing the same goal of human flourishing.

The greatest weakness of Allen’s otherwise convincing recalibration of liberalism is her unwillingness to fully confront the technocratic excesses that too often threaten genuine self-governance. Allen rightly challenges the ways in which crony capitalism has often undermined the dignity of communities. But the overreach of the state—whether banning certain topics in school or implementing excessively stringent environmental regulations—just as often robs people of the autonomy so necessary for flourishing. A genuine accounting of democracy’s ailments must reckon with the uncomfortable fact that human freedom is being squeezed by both the government and corrupt economic practices. Though at times Allen seems clearly aware of this fact, she never fully addresses the nature of the modern state.

All in all, Danielle Allen’s Justice By Means of Democracy provides the road map that contemporary liberalism so desperately needs. Besieged on the left and the right, Allen shows how liberalism can reconstitute itself to address the problems of the 21st century. Many today feel they have been forgotten by the American regime. Democratic liberalism of the kind articulated by Allen is a potential solution to their problem.

Jeffery Tyler Syck is an assistant professor of Political Science and American Studies at the University of Pikeville.

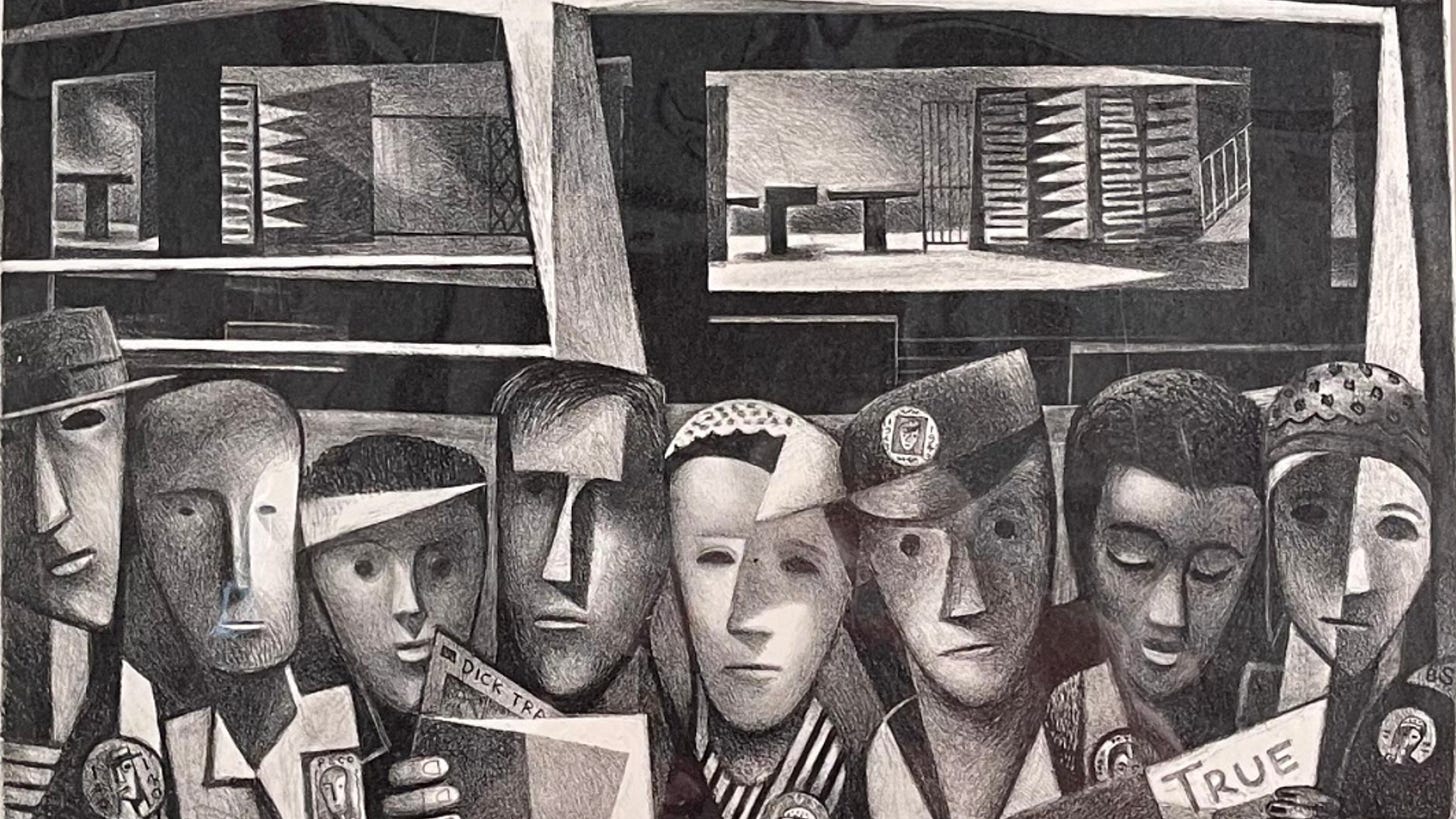

Image: "Underground Railway Shift - The Second Front," Benton Murdoch Spruance, lithograph, 1943.