Reflections on Right-Wing Cancel Culture

Justifying censoriousness because “the left started it” is dumb. It’s also untrue.

“The Left started it.”

That was the common retort from right-wing X accounts like Libs of TikTok and their supporters, who attempted and often succeeded at getting people fired for making tasteless social media posts about the assassination attempt on Donald Trump back in July.

Most of their victims weren’t public figures but regular Americans like Home Depot employees, firefighters, chefs, and school counselors. This was fine and good, many argued, because it constituted sweet revenge for cancel culture excesses driven by the Left. At The American Spectator, Nate Hochman claimed that the only way to get the Left to change is to make them “understand, at a visceral level, the penalties for the system that they themselves constructed—so much so, in fact, that they are no longer interested in perpetuating it.”

But the idea that the Left invented cancel culture is a poor and convenient excuse for satisfying the intolerant impulses that have tempted all humans throughout history regardless of political orientation. Using similarly flawed logic, Catholic persecution of paganism was justified since emperor Nero “started it.” Protestants would be entitled to persecute Catholics, as Protestant states frequently did, because the Church excommunicated Luther, banned his books, and punished heretics. We would also have to reevaluate the censorship and persecution in socialist and communist states. After all, Marx, Lenin, and Stalin were all subject to harsh censorship from various political and religious factions of the “bourgeoisie” before the establishment of the Dictatorship of the Proletariat turned the censored into censors.

A Brief History of Right-Wing Cancel Culture

Progressive ideas have often been confronted with hostility by conservatives and proponents of the status quo. In On Liberty, the high priest of liberalism, John Stuart Mill, warned that the cultural norms of 19th-century Victorian England created “a social tyranny more formidable than many kinds of political oppression.”

This sort of “social tyranny” has also manifested itself in the United States at decisive historical moments where first principles were at stake:

In 1850, a professor at the University of North Carolina named Benjamin Sherwood Hedrick faced severe repercussions for his public support of anti-slavery Republican presidential candidate John C. Frémont. Students, faculty, and local newspapers condemned Hedrick, and he was even burned in effigy on campus. When he was fired and forced to flee North Carolina, The Standard newspaper boasted about successfully removing “an avowed Fremont man” from the university and the state.

During World War I, the first Red Scare targeted anti-war protestors and those suspected of holding or sympathizing with socialist and communist views. In 1917, the Columbia University history professor Charles Beard resigned in protest after the Board of Trustees dismissed two professors opposed to the war. The New York Times editorial board celebrated Beard’s resignation, praising the school for cracking down on doctrines “dangerous to the community and to the nation” and ridiculing the idea that “academic freedom” must include “poisonous teachings.”

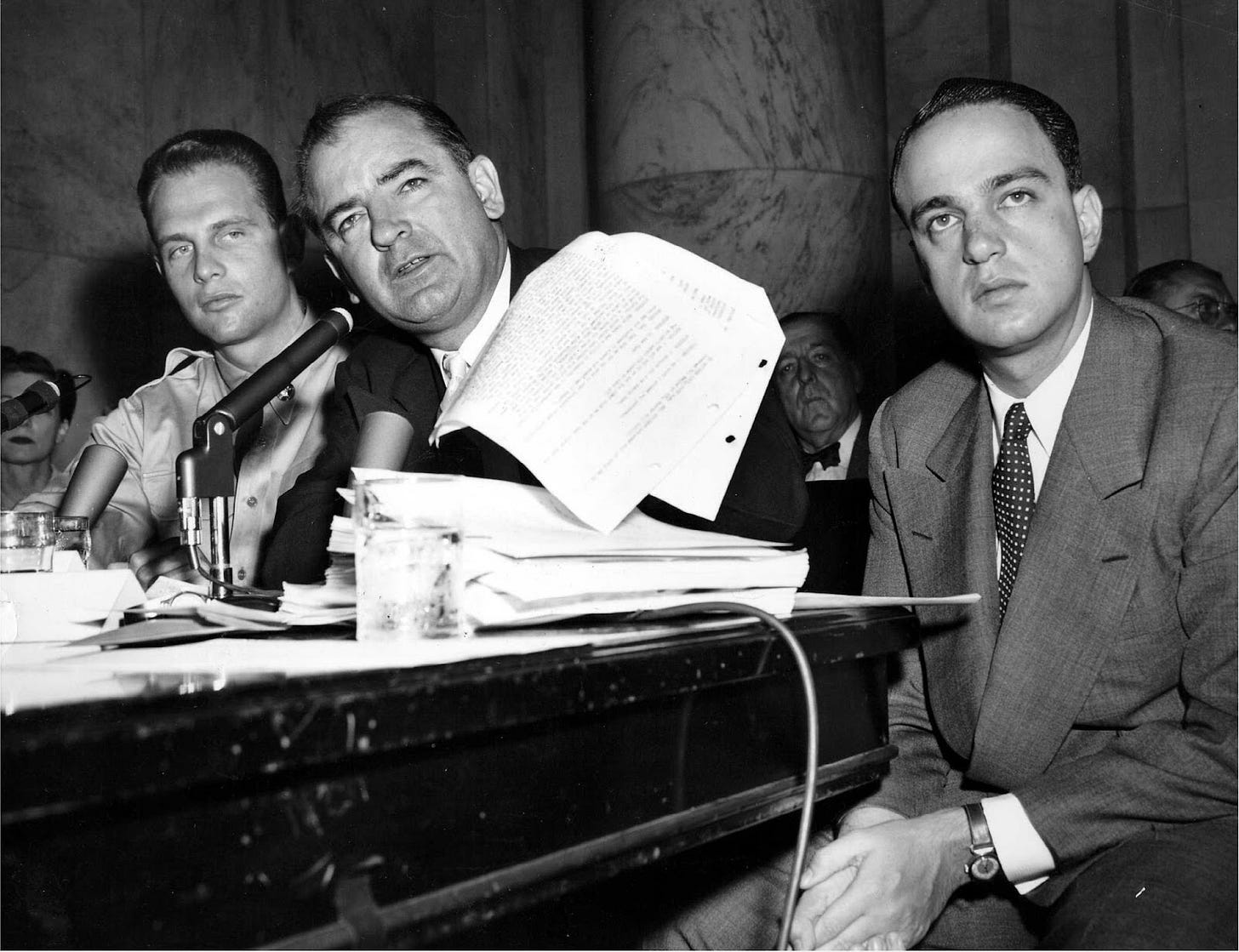

During the second Red Scare of the 1940s and 1950s, the fear of communism led to the widespread blacklisting and firing of individuals suspected of having leftist sympathies. Over 378 teachers in New York City alone were dismissed, forced to resign, or take early retirement due to suspicions of communist involvement. Meanwhile, over 300 writers, actors, directors, and producers were placed on a Hollywood blacklist. The conservative American Legion criticized concepts like “academic freedom” and questioned whether communist professors should be allowed to teach on campus.

Cancellation attempts continued throughout the Civil Rights era, including the firings of those participating in activism to promote equal rights. In 1960, civil rights activist Reverend James Lawson led lunch counter sit-ins in Nashville. Lawson was enrolled at Vanderbilt University’s divinity school at the time, but, after a local newspaper described Lawson as an “agent of strife” university officials deemed his Gandhi-inspired nonviolent protest techniques too radical and expelled him.

Finally, spurred by the Satanic panic and the rise of the Evangelical Right, conservatives in the 1970s and 1980s coalesced to root out what they viewed as corrupting ideas, targeting wide swaths of art, music, and literature. Mundane pursuits like Dungeons & Dragons and heavy metal music ended up in the crosshairs. In 1981, a coalition led by the Moral Majority promoted a national boycott of companies that sponsored or advertised on TV shows they deemed offensive due to “excessive sex, violence, and profanity” in an attempt to get such programs removed from the airwaves.

The Need for Principled Defenders of Free Speech

These examples underscore a critical lesson: the original sin of cancel culture does not rest with any single ideology or group, but rather with our species' hard-wired tendencies towards tribalistic behavior and the self-righteous urge to punish outgroups who transgress taboos. 2,500 years before the advent of social media, the Buddha aptly warned against giving into anger with its “poisoned root and honeyed tip.” This dynamic explains the endless battles ginned up by Very-Online Culture Warriors, including those involved in recent attempts to cancel left-wingers who post distasteful things about Trump.

But no one can claim a moral high ground according to which the ends justify the means of cancel culture. Those who are serious about fostering a resilient culture of free speech should instead commit to resisting the honeyed tip of tribal outrage and thus help prevent the spread of its poisoned roots.

History provides numerous role models who have paved the way.

The great orator Frederick Douglass was subjected to multiple cancellation attempts for his abolitionist speeches. He was almost killed by a mob shouting “kill the n*gger” after an 1843 speech in Pendleton, Indiana, and was shouted down by another mob in Boston in 1860. His response was not to demand the censorship of pro-slavery advocates. In his essay “A Plea for Freedom of Speech in Boston,” Douglass wrote that “there can be no right of speech where any man, however lifted up, or however humble, however young, or however old, is overawed by force, and compelled to suppress his honest sentiments.” Douglass also made the important point that free speech is not only an individual right of the speaker, but in fact a common good that benefits all, and thus, “To suppress free speech is a double wrong. It violates the rights of the hearer as well as those of the speaker.”

Douglass’ civil-libertarian ethos was ultimately reflected in First Amendment jurisprudence. In the landmark Brandenburg v. Ohio decision, the Supreme Court held that the First Amendment protected the speech of a KKK leader who warned that he might take action against “N*ggers” and “Jews” if the government didn't. Thurgood Marshall, the first African American Supreme Court Justice, grew up in the Jim Crow era, graduated from a segregated school system, and fought against the oppressive and censorial reality of Jim Crow. Despite this, he voted with the majority in Brandenburg, since he recognized that, as one commentator put it, “liberty and equality, properly understood, complemented each other.”

More recently, the author Salman Rushdie has lived with the consequences of exercising free speech, enduring countless cancellations, threats, and violence, culminating in a near-fatal attack in 2022. Yet throughout his forty-year ordeal, Rushdie has remained a steadfast defender of free speech, advocating for the rights of even those who abhor his work and wish him harm.

Douglass, Marshall, and Rushdie all paid a high price for their principles, standing firm against censorship and persecution. Their sacrifices underscore the urgent need for a collective commitment to uphold the principles of a vibrant culture of free speech, which will allow us to respond to ideas we loathe with scorn or criticism without resorting to punitive measures that undermine the pluralistic foundation of free societies.

We must follow their example and reject the poisoned roots of tribalistic anger and the false justification of cancel culture just because “the other side started it.”

Jacob Mchangama is the Executive Director of The Future of Free Speech and a research professor at Vanderbilt University. He is also a Senior Fellow at The Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression (FIRE) and the author of Free Speech: A History From Socrates to Social Media.

Follow Persuasion on Twitter, LinkedIn, and YouTube to keep up with our latest articles, podcasts, and events, as well as updates from excellent writers across our network.

And, to receive pieces like this in your inbox and support our work, subscribe below:

"These examples underscore a critical lesson: the original sin of cancel culture does not rest with any single ideology or group, but rather with our species' hard-wired tendencies towards tribalistic behavior and the self-righteous urge to punish outgroups who transgress taboos.”

This is the key sentence in the article. Admittedly I speak as one trained in anthropology, but the depth of what the author refers to as ‘tribalism' is actually something even deeper - territoriality. Our genetic inclination to territoriality goes so far back into the mists of our animal heritage that we would never be able to find its origins. But its effects are strong because they had to be. A group’s survival often depended on the lengths to which its members would go if they had to in order to defend their ground and their own, and those lengths often included the sacrifice of life itself. Therefore natural selection worked to maintain it at a high level. We make somewhat light of it in our regular references to phrase like ‘the home court advantage’, but it is very and deeply real.

As humans we have extended territoriality out of the purely geographical and added it firmly in the intellectual and emotional spheres of our existence. The instinct is to draw the line, and we do so at a level well below our thought processes. They only come into play as we decide where the line is to be drawn, and not whether or not to draw it.

The Nature v Nurture argument is as old as we are, and there’s a good reason for that. As a species that prizes our sense of ourselves and our ability to make decisions on our own, we find it hard to admit that we are also prey to some forces deeper than our self-vaunted thought processes. But until we recognize the power of those deeper instincts, we will be powerless to free ourselves from them when we have to.

Those forces fuel our nationalism and our religious, political, and social divisions. They are the basis of our stubborn determination to focus more on what we believe differentiates us from ’those others’ than on what we share as human beings, all too often in the course of which differentiation we descend into that uniquely human catastrophe we call war. It is a force all too well understood and used by demagogues like Donald Trump and all his predecessors, by all the authoritarians who used ‘fear of the other’ to maintain their power.

We have been prey to those forces for as long as we’ve been human, but up until August 6th, 1945, their effects, while increasingly horrendous as science and technology gave the means to make them so, were not at the extinction level. Now we’ve reached that pinnacle, and our future as a species, along with all other life on earth, is going to depend more than ever on our ability to understand and to deal far more successfully with what we’ve been just playing with all this time.

Until introductory logic classes are required there will be no way to stop this. Once we eliminated the tools for informal and formal logical argument then only Gorgias and Protagoras remain, persuasion without regard for truth.