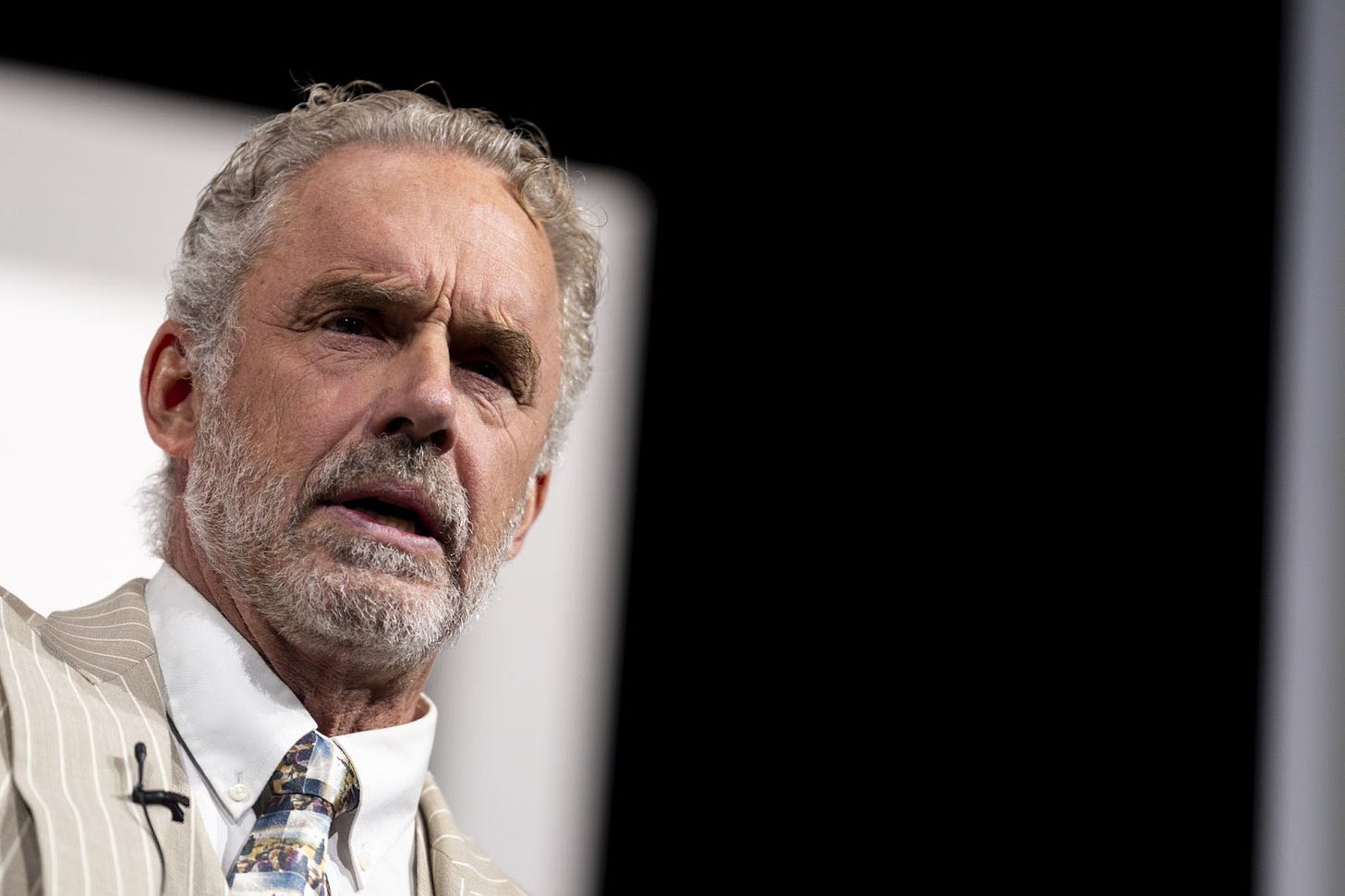

Reflections on the Jordan Peterson Generation

His rise, his meltdown, his fall.

I am, I suppose, in the Jordan Peterson generation. I was in my late twenties when he rose to success and I was probably in the category of young men he believed himself to be speaking to. I was certainly not someone who would say he saved me from the dragon of chaos that was my untidy room, nor was I ever impressed with his ridiculous theories about lobsters. I just found him mildly interesting. The peak of my Peterson exposure was to listen, several times, to every episode of his 2017 biblical lectures series. While they are frustrating, mad, and sprinkled with unfalsifiable gibberish and self-help gospel, they are also tantalizing. Anyone who listened to them listened to Peterson changing the religious conversation in real time.

And not only. At the peak of Peterson’s fame in the late 2010s he seemed to be waging (often very successfully) a sort of one-man crusade against the complacent orthodoxies of liberal culture. He spoke for traditions ranging back to Carl Jung, Erich Neumann, the greats of psychology—and well beyond that. Read his books, listen to his many lectures, and to his fervent television debates, and it often felt that in him, and him alone, a sensibility survived that married secular humanism with deep faith—and that was wholly untouched by political correctness or wokeism or (Peterson’s particular bête noire) the reigning neo-Marxism of the academy.

For legions of Peterson’s fans, the provocativeness of so much of what he was saying wasn’t really the point but more a kind of necessary protective barrier for the deeper traditions he espoused. “Come for the scandal, stay for the content” emerged as a sort of tagline for his appeal. And that seemed all the more impressive given the overwhelming professional and public pressure placed on him at the height of the Woke movement—which nonetheless did not compel him to retract even his more controversial stances. “There was plenty of motivation to take me out, it just didn’t work,” he said in his contentious British GQ interview with Helen Lewis.

Naturally not everyone was so sympathetic to Peterson. The renowned theologican David Bentley Hart, for instance, called his biblical lectures “ghastly,” described Peterson as a “joke,” and claimed that there could be no reason for any young person to listen to the lectures that was not a reflection of intellectual impoverishment combined with a need for a self-help Father figure.

I do need to take issue with this facile dismissal. Firstly, I don’t think this is a fair criticism. Yes, Peterson has certainly always had a skim-read understanding of a lot of thinkers, and tended to engage quite sweepingly with strawmen/clichés, something that has got worse with time (by this point “postmodernneomarxists” is completely meaningless), and he certainly leans towards the mad, but he was still reasonably well read and perhaps more obviously, he was exactly what he was: an eccentric Canadian psychology professor. If you expected that, you got it, and it was interesting and infuriating in due measure; but if you expected a savior of religious learning who could supply a robust pragmatic resurrection of the biblical traditions, not so much.

Secondly, the fact that young men want self-help that is rooted in intellectual credibility or a reminder of the relationship between meaning and responsibility is hardly something to condemn them or Peterson for. The Christian perspective on this would be that this should be the role of the pastor or preachers, and the fact is that Peterson for a moment fulfilled a vacuum probably left in a lot of young men’s lives by the failure of well-meaning but inept youth pastors. His self-help advice wasn’t really Christian, but it seemed to anecdotally help a lot of young men. I don’t think that was or is something to mock.

And something happened in this era to Peterson that it’s hard to solely blame him for. He was both idolized and condemned in a way so extreme that it seems impossible that anyone could go through it with their ego intact. Wherever he went, young men would be thanking him for saving their lives and interviewers would be asking why he wanted to spread hate speech, with little in between. Peterson always seemed to have a slightly forthright streak that bordered on anger, and while in his early interviews he remained composed, by 2018–19 he often seemed to become more tearful or angry in interviews, suggesting that these extremes took—unsurprisingly—an emotional toll.

Then, I suppose you know what happened. I am not a doctor, and I don’t know whether eight days in a medically-induced coma to treat benzodiazepine withdrawal is likely to have a detrimental effect on your cognitive state, but I don’t think I’m in a minority in suggesting that Peterson’s state of mind in the era after his return from collapse has never been the same. The pre-Covid Peterson was sharp, concise, and formidable, whatever you thought of his points. Now he cries regularly during interviews, meanders in his responses, posts videos addressed to literally “all Christians” or “all CEOs,” berates the camera angrily, talks over guests he interviews on his podcast, all while his content has become increasingly messy, at times nonsensical. His ARC Conference speeches are so absurd they border on self-parody, and his latest book is tough sledding even for a sympathetic Peterson fan. His strange appropriation of Christianity during this time was hard to take, and to cap it all off he signed a deal with The Daily Wire to host his podcast and start making paywalled content on everything from marriage advice to the gospels. Peterson’s transition from interesting professor to culture war savior was complete, and it was not the same Jordan Peterson as the one who first appeared on Canadian TV to object to an obscure bill about pronouns.

So why do we still care? There is certainly an element of the car crash phenomenon, where the traffic builds in the opposite direction simply because everyone can’t help but slow down to have a look. Not to mention that the more Peterson displays angry assertive energy the more he fosters a love-hate response that becomes its own echo chamber. His attitude, especially when it comes to adopting Christianity, has reached a painful level of pomposity, perhaps reaching its climax in his condemning of the commentator Candace Owens on Twitter with pseudo-biblical language, in which he called her a “Pharasaical pretender” and accused her of using Christianity to foster her own success. For someone who does interviews in blazers covered in saints and sells courses on the gospels behind a Daily Wire paywall in spite of not actually being a Christian, the accusation of hypocrisy is almost painful in its irony.

Yet for all that, it remains a mistake to entirely dismiss Peterson—or, maybe more crucially, to write off his appeal to so many people as a kind of collective delusion. Peterson is still capable of saying things that are interesting, and of hinting at conclusions many thinkers are nowhere near. He is, or was, at the very least determinedly unique and surprising. If we were to compare Peterson to, say, Wes Huff, a popular evangelist, the two are an entirely different experience. Nothing that Huff is saying suggests any particular individual insight—it could all be found on any apologetics bookshelf. He is just retreading established ground and repeating it like a salesman.

And while Peterson’s Christianity lectures contained plenty of nonsense, it wasn’t just nonsense. There were plenty of insightful observations throughout, plenty of moments that made you go “huh”—maybe, above all, his tackling of why the adoption of religion made sense from an evolutionary perspective. Peterson just came at everything so sideways and churned the riverbed up so much that he —perhaps you might even say incidentally — produced something weirdly fascinating.

Is it his fault millions of fans interpreted that feeling of insight with the belief in his status as savior? Perhaps. Peterson certainly rode the wave, and he seemed to believe his own hype as much if not more than anyone. Being vilified didn’t help, no doubt, but in reality there weren’t enough people suggesting everyone just needed to shut up and let him go be a psychology professor who did the odd public lecture series.

The trajectory of Peterson’s career may have been an inevitability of an ego that couldn’t say “that’s enough,” or it may be the fault of those who expected him to be more than he was. Either way, the failure of Jordan Peterson is a failure of culture, a failure of public intellectualism, a failure of a new media system that seemed to promise a positive replacement to the legacy media and instead produced siloed professional talkers who tour podcasts becoming steadily more unhinged and self-reinforcing.

He won’t be the middling psychology professor he was because he’s Jordan Peterson now, that guy everyone knows. If he was my dad (he is about the right age), I’d wish he took up fishing or some hobby and went and quietly wrote a book about something he loved, spent some time with his grandkids, maybe got an allotment. However easy it may be to mock his bizarre recent lectures and comment on his downfall, I sincerely hope someone in his family is brave enough to tell him that and he is able to find some retirement peace, maybe even eat a salad once in a while. The no-name Toronto professor he used to be deserves better.

A version of this article appeared on This Isle is Full of Noises.

Matt Whiteley is a freelance writer from England, and can be found on his Substack This Isle is Full of Noises.

Follow Persuasion on Twitter, LinkedIn, and YouTube to keep up with our latest articles, podcasts, and events, as well as updates from excellent writers across our network.

And, to receive pieces like this in your inbox and support our work, subscribe below:

Great piece Matt. Very fair and thoughtful. Dr. Peterson is the wounded warrior who led Picket’s Charge straight up the hill against the woke cannons firmly ensconced in our culture’s high ground. That’s courage, action, commitment, sacrifice. More than I’ve done. I post firmly convicted comments on Substack. He sacrificed his reputation and mental health. And I kinda get it. I, once, was a committed centrist proud of my ability to fight for both sides. Now I’ve transformed into the belief the Left cannot be saved from the grotesquerie it has become and is no longer worth defending. That inner journey is sculpted by the larger cultural entropy and takes us all to uncharted territory. I’d bet you, privately, feel the same. So Jordan isn’t worth listening to now. I get it. I tip my cap and say my thanks for what he’s already done.

I know a lot about benzodiazepine withdrawal and something about Peterson's case. Yes, its brutal, can be fatal, and very likely would impair cognitive ability. Staying on benzodiazepines also harms cognitive function ( just like alcohol). Very sad, another brilliant man nearly destroyed and certainly harmed by psychiatric drugs. I recommend the book UNSHRUNK by Laura Delano, and the documentary "Medicating Normal."