Remember Martin Luther King Jr.?

Kendi's antiracism won't work, but King's does. It is time to revive the nonviolence movement.

By now, we surely have the answer to Langston Hughes’s question, “What happens to a dream deferred?”

“Does it dry up like a raisin in the sun?” the poet wrote. “Maybe it just sags/like a heavy load./Or does it explode?” We have seen the explosion.

After the murder of George Floyd and the protests that followed, the belief that Martin Luther King Jr.’s dream had been deferred too long prompted the embrace of a corrective ideology: antiracism. Audacious and comprehensive, antiracism swept through institutions with avenging fervor. But was antiracism the answer? Or does modern antiracism risk deferring the dream further still?

The dream of Dr. King, Bayard Rustin, Ella Baker and John Lewis that “this nation would one day rise up and live out the true meaning of its creed” was born of the philosophy of nonviolence. That is the dream America must reclaim.

I grew up in the multicultural middle-class suburb of Culver City, California. My classmates were White, Jewish, Asian, Latino, Middle Eastern and Black. Being mixed Black and White myself, I more or less fell in with everyone. From elementary school to high school, I generally had the impression that Dr. King’s prophetic vision of a promised land of racial harmony had been achieved. My family was integrated; so was my school. I had friends of all races in a country where, 50 years earlier, we would not have been able to eat together at the same lunch counter. My life was proof that the dream had been fulfilled.

And for me, it has been. Some people will be upset to hear me say this. But I have not experienced racism in any way that has had a lasting impact on me. Yet I also know that the work of the nonviolent movement is incomplete.

I see this in two ways. First, the experiences of many in Black America are far from my own; this is a country where deep racial problems remain. Second, the substance of King’s teachings have not been adequately taught to Americans. The rise of antiracism—and the excesses of the modern social-justice movement—are a reflection of both facts.

Ibram X. Kendi is 38, four years older than I am. Like most of our generation, Kendi learned of King as the pre-eminent figure in the recent history of American, and Black, social progress. That is probably why the young Ibram Rogers (his birth name) chose to speak as if in King’s voice during an oratorical contest as a high-school senior.

Kendi, probably America’s foremost proponent of antiracism, recounts this occasion in the introduction to his bestselling book How to Be an Antiracist. Kendi imitated the cadence of King’s “I Have a Dream” speech to deliver an address that chastised Black Americans for falling short of their potential. It is a moment Kendi recalls with shame: “I was a dupe, a chump who saw the ongoing struggles of Black people on MLK Day 2000 and decided that Black people themselves were the problem.”

Kendi moved from a repudiation of this early flirtation with a superficial sort of Black conservatism to a repudiation of the narrative of American racial progress following the Civil Rights movement—in other words, the narrative that I would long embrace, and that I still partially hold to.

That narrative of American racial history tells us that the major victories against racism in this country were won with the passage of the Civil Rights Act and the Voting Rights Act. It is a story that says the struggles of the Black community following Dr. King’s death are largely of our communities’ making, and are our responsibility. It is a telling that seizes upon the election of Barack Obama, America’s first Black (and mixed race) president, as the symbolic culmination of King’s integrationist dream.

For Ibram Kendi, Alicia Garza, Nikole Hannah-Jones and the leaders of the antiracist movement, this narrative is dangerous, weaponized in the form of a color-blind ideology that obliterates the reality of Black experience and White supremacy. Antiracists agree that race is fundamentally a social construct yet antiracism insists on our racial categories, so that the racism in society is not overlooked.

As the post-racial commentator Thomas Chatterton-Williams told me in a recent conversation, “I just don’t see how you can hyper-focus on racial differences, and also believe that you’ll ever transcend them.”

For all of my own post-racial views, I wonder if the antiracist consensus has a point. There are realities of the American past and present that conspire to make life more difficult for African-Americans, and this bleeds into our psychology. Can we name these realities without naming race?

But even so, this does not negate the patriotic idealism of a young Senator Barack Obama. Nor does is it nullify the racially transcendent exhortations of Martin Luther King. For the power of nonviolence stems from principles that are deeper than race—principles that are indispensable for the future of social justice. King enumerated these in Stride Toward Freedom:

· Nonviolence is humanizing. It “does not seek to defeat or humiliate the opponent, but to win his friendship and understanding.”

· Nonviolence is forgiving. It is aimed “against forces of evil rather than against persons who happen to be doing the evil.”

· Nonviolence is suffering. It requires a willingness to endure the assaults of opponents without returning in kind. King quoted Gandhi as saying, “Suffering is infinitely more powerful than the law of the jungle for converting the opponent and opening his ears which are otherwise shut to the voice of reason.”

· Nonviolence is loving. “The nonviolent resister not only refuses to shoot his opponent but he also refuses to hate him. At the center of nonviolence stands the principle of love.”

· Nonviolence is active. The practitioner is one whose “mind and emotions are always active, constantly seeking to persuade his opponent that he is wrong.”

· Nonviolence is hopeful. It “is based on the conviction that the universe is on the side of justice. Consequently, the believer in nonviolence has deep faith in the future.”

I work for Braver Angels, a bipartisan organization that facilitates political and crosscultural dialogue, among many other projects. Since the surge of antiracist activism and the new popularity of diversity, equity and inclusion programming, I have received an avalanche of requests. There is tremendous interest across America in achieving equity for the African-American community, and making institutions more inclusive rather than settling for the tokenism of the past. There is a desire to embrace the ends of social justice, and many truly want solidarity with the Black Lives Matter movement.

But, almost invariably, these are quiet calls of distress from parties who do not know how to deal with the excesses of this ideological movement. Government agencies and elected officials cannot start productive conversations between communities and law enforcement because a new generation of activists overwhelms older community representatives, preferring demonstration to negotiation. Departments of education and corporations cannot bridge divides because of disagreements over the implications of privilege. Different parties “standing to speak” often make White people (and others) feel marginalized and disrespected. And still, antiracist efforts leave people of color and members of the LGBTQ community feeling diminished and unheard.

A criticism of antiracism from the cultural commentator John McWhorter is that it is a perspective that roots all American reality in an evil for which there is no clear path to salvation. “Now, not only does the American individual harbor the original sin of being born privileged, but America itself is a product of a grand original sin, permeating the entire physical, sociological, and psychological fabric of the nation, to an extent no one could ever hope to undo, and for which any apology would be insufficient to the point of irrelevance.”

In my experience, the fundamental problem is that antiracism concerns itself chiefly with seizing and exploiting social and political power to remedy the imbalance of power in society. The art of building relationships despite differences, which can yield stable and enduring consensus, is undeveloped. Modern antiracism does not see beyond confrontational activism. To be clear, its leading proponents do not advocate violence. But their ideology fails to understand what the nonviolence movement intimately knows.

Martin Luther King Jr. was concerned with power too, and came to focus the tools of nonviolence upon achieving power within society. But he had a more expansive understanding of power than Kendi. King wedded the persuasive and moral power of agape love—a divine form of loving charity for others—to the aim of political equality, using a formula that dignifies the humanity of both the seeker of justice and the opposition.

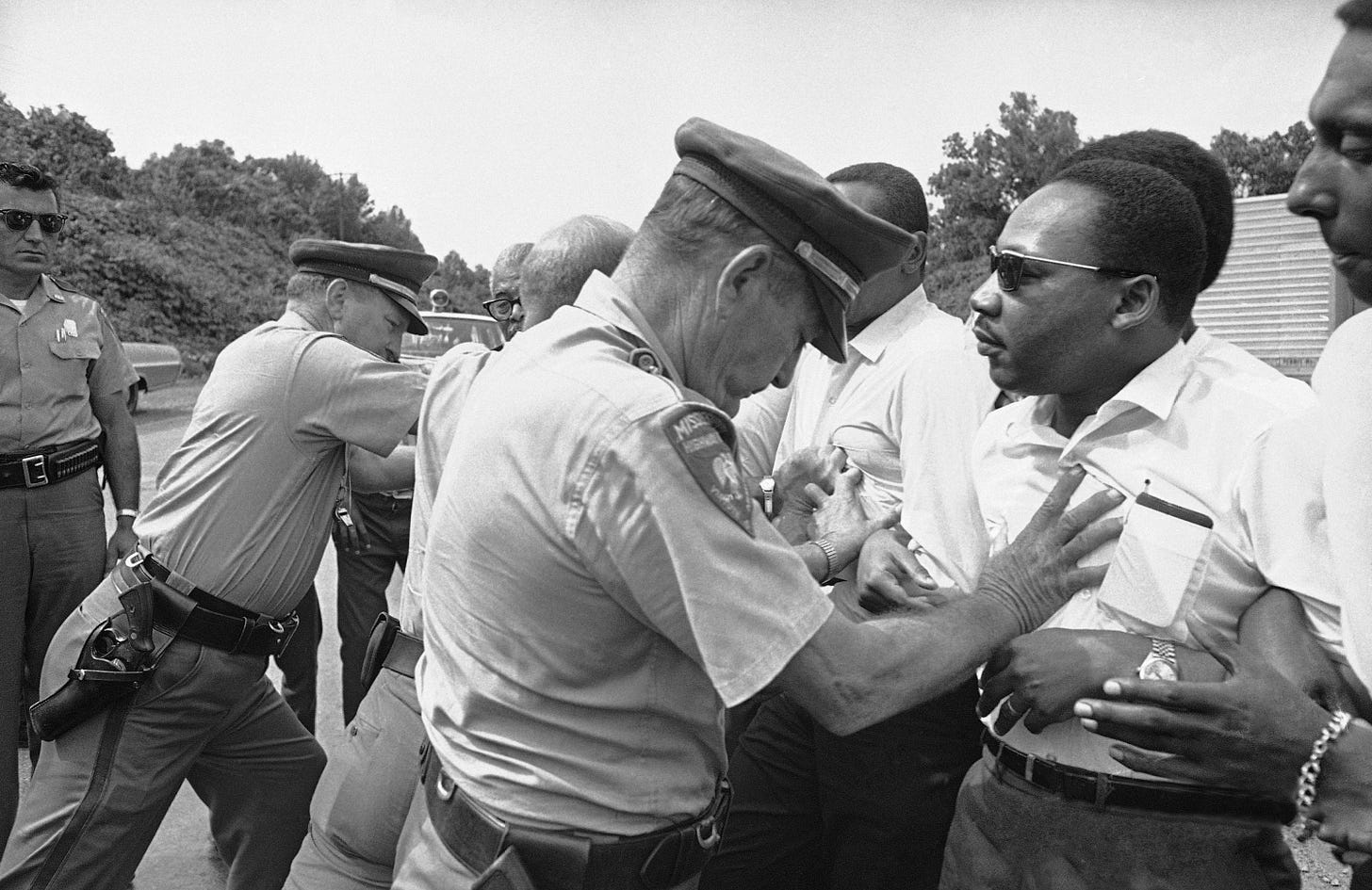

King maintained this ideal in the face of the hatred he endured, without ever retreating from the moral foundations of nonviolence. It is well that he didn’t. Achieving civil-rights reforms required a critical mass of diversified support that was only possible through the humanizing power of nonviolence. The breadth of this support stood in contrast to that of the more aggressively militant social movements that rivaled it.

And yet it is those movements that provide more of the ancestry of today’s social-justice activism. The strident echoes of “Black power!” ring loud in today’s activism. Malcolm X and Stokely Carmichael are upheld as role models in today’s Black freedom struggle. Angela Davis remains a patron saint of modern social-justice work. Antiracist activists even recast humanizing figures like James Baldwin and King himself as closer to traditional radicals in order to link them to today’s culture—without committing themselves to the substance of those men’s perspectives.

Malcolm X, along with all the other figures I mentioned above, are worth understanding, respecting, even admiring, for their contributions to the Black-freedom struggle. Even so, we must recognize their errors and limitations. The more conventional modes of militancy were appealing in the 1960s for precisely the reason they are appealing today: They are easier than nonviolence.

Nonviolence is a harder discipline, morally and strategically. It requires mastery of the inner self in a way that silences the roar of anger and raises the voice of conscience. It requires unending forgiveness for those who wrong us. And it demands that this spirit be mobilized in our activism.

The Indian philosopher Karuna Mantena wrote about the nonviolence of Gandhi (which directly inspired the work of King and his philosophical tutor Bayard Rustin), and how nonviolence expressed itself in the Indian independence movement:

Marches were…to be slow and deliberate. Songs and prayers cultivated unity, solidarity, and emotional resolve among protestors…To onlookers they communicated something equally important, an inner calm and resiliency that is very different from what we now associate with the paradigm of disruptive protest…Nonviolence chooses to whisper rather than scream, to draw people close and cultivate the willingness to listen.

A willingness to hear the opposition receded with the death of Dr. King. This was a consequence not just of the absence of King’s voice but the presence of his success. The heirs of the Civil Rights movement found themselves at the forefront of well-placed organizations, elected to office and esteemed by mainstream American society. Some such leaders, like John Lewis, faithfully embodied the spirit of nonviolence throughout their careers. Most, like Jesse Jackson, would find themselves joining with more conventional activists and/or becoming absorbed into the broader ecosystem of Democratic Party politics, where the language of nonviolence began disappearing from their vocabularies. The spirit of the movement was never nourished in the halls of power.

Even as idol worship swelled around King’s memory, his principles faded from the mainstream of American discourse. But, back when petitioners were establishing the Martin Luther King Jr. Day holiday in the 1980s, his teachings were still visible in local nonviolent movements. Examples include BUILD (Baltimoreans United in Leadership Development), led by former leaders of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, notably the Rev. Vernon Dobson. BUILD used nonviolent organizing methods to rally the community of Baltimore to raise funds so that all the city’s high-school graduates could attend college. The work of BUILD continues to this day.

Another example is the EBC (Eastern Brooklyn Churches), which used nonviolent principles to push the city to renovate parks and install hundreds of street signs. Their members worked together across religious and ethnic lines (Protestants, Catholics, African-Americans, Poles and Italians) to win the support of Brooklyn’s political establishment, and ultimately to build more than 4,000 single-family homes in the borough.

The organization I represent, Braver Angels, engages in political organizing and dialogue through methods partly motivated by principles of nonviolence too. Another example is the Theory of Enchantment developed by Chloé Valdary, a diversity, equity and inclusion program that explicitly applies many of these principles in training programs for companies across America.

We think of nonviolence as a form of activism. Clearly, it is more.

It may be hard to believe that the universe is on the side of justice. It may be hard therefore to have faith in the future. But perhaps we may believe that the human heart tends to be on the side of love. This may be enough to remind us of nonviolence’s capacity to change America.

The question is, Will we forget the strides that we have made as a country to humanize one another, even in the face of mass incarceration and the persistent inequality of opportunity? Will we forget the moral power that touched the conscience of our nation in a previous generation?

Whereas racism produced disparities still suffered by many in Black communities, nonviolence opened the door for a historic expansion of the Black middle class. Whereas racism distorted our institutions, nonviolence pried apart the cultural centers of America to recognize African-Americans with the highest stations of honor. Whereas racism pitted us against each other in warring tribes, nonviolence brought us that much closer to becoming family. Whereas racism is the great enemy of American idealism, nonviolence is its truest ally.

The standards of nonviolence are high. They are out of fashion. They are hard to commit to. But we must do so. For in this age, we have not yet tried to wield love in all its power to advance social progress and racial healing.

Let us move beyond the limits of antiracism. Let us strive again toward the dream.

John Wood Jr. is a writer, speaker, musician and former nominee for Congress. He serves as national ambassador for Braver Angels.

Beautifully written and analytically correct. To eliminate racism, one must change hearts and minds, not just conduct. As the Stoics taught us, violence cannot do that. If anything, it hardens inclinations into immovable concrete and elicits resentment. One must disabuse, and that requires understanding the root cause of another's belief. Antiracism as currently configured completely fails to acknowledge this truth and instead takes the easy, emotionally satisfying tack of confrontation and use of war-like techniques to best, intimidate and cow. It's a methodology doomed to failure, and unless and until the antiracism movement figures that out, things will only go backwards and cause MLK to roll over in his grave.

Before the conversation can begin, we need to agree on a definition of "equal." MLK defined equal in terms of political rights and opportunity. The antiracists and even more moderate politicians define equality in terms of percentages and outcomes. Count me among those who favor the former term.

How do the proponents of structural racism theory account for President Obama's election? Or the great successes and accomplishments of many Americans who are black?