Remembering Donald Kagan

From ancient Greece to the New York Yankees, a former student remembers the brilliance of historian Donald Kagan.

Donald Kagan, who passed away on August 6 at the age of eighty-nine, had a wonderful life. His family, his friends, his colleagues, his readers, and his students all reaped the benefits.

When I first met Kagan in the 1970s at Yale, where I went to do a doctoral degree in history, I was fascinated. Having read his book The Outbreak of the Peloponnesian War (1969), the first of what would be a four-volume history of the war, which made his reputation, I knew he was a great scholar. I had not known, though, that he was an original. Kagan was brilliant, astute, warm, fluent, and constantly in motion. He was an administrator, educator, and wit, then at the beginning of a career as a public intellectual. He was comfortable quoting the maxims of Renaissance humanist Francesco Guiccardini (1483–1540) and the batting statistics of baseball great Ted Williams (1918–2002).

Born in Lithuania in 1932, Kagan came to the United States at the age of two. He loved America with an immigrant’s affection. He was raised in the tough neighborhood of Brownsville, Brooklyn. He went on to become a renowned classicist and historian, with teaching positions at Cornell, then at Yale, where he spent most of his career. At Yale he was Sterling Professor of Classics and History, chair of the classics department, master of Timothy Dwight College, and dean of Yale College. A confirmed sports fan, he also served as Yale’s acting director of athletics. His many honors include the National Humanities Medal and the Jefferson Lecture, the federal government’s highest honor in the humanities.

A passionate defender of Western civilization and a supporter of Ronald Reagan’s peace-through-strength foreign policy, Kagan was a conservative at a liberal university. He was outspoken and courageous, and he knew how to take a punch.

Like the Athenian leader Pericles and the American President Franklin Delano Roosevelt, whom he admired, Kagan was a happy warrior. Unlike those men, Kagan was not an aristocrat; but he shared their nobility of spirit. He imparted a sense of the grandeur of history. He saw humans as frail, vain, and mistaken but capable of achieving peace and prosperity and creating sublime works of the imagination. It is a vision akin to that of the author whom Kagan devoted much of his career to studying, the historian Thucydides. A classic realist, Thucydides also had a sense of the moral foundations of civilization and of their fragility.

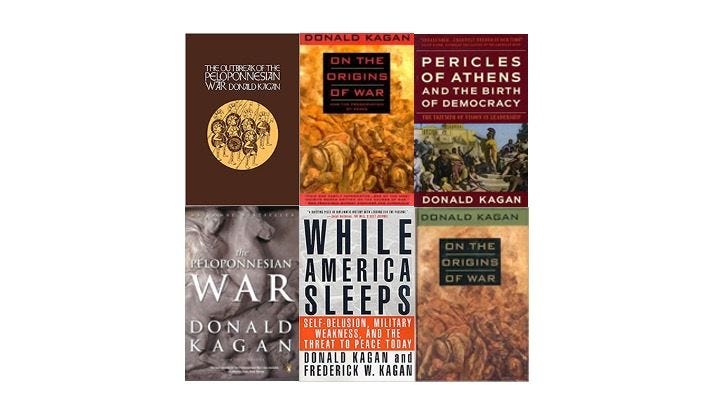

Kagan wrote many books in addition to his series on the Peloponnesian War. The most celebrated of them is probably On the Origins of War: And the Preservation of Peace (1995). Five years later, he and his son Frederick published While America Sleeps: Self-Delusion, Military Weakness, and the Threat to Peace Today. These books cover a wide range, from classical Greece to just yesterday, but have common themes. Kagan was a historian of statesmanship. Increasingly, he became interested in what it takes to preserve peace.

Peace, Kagan argues, is not the natural state of mankind. Without an effort to preserve peace, a country is likely to sink into war. What is needed is a vigilant and tireless struggle that includes both military preparedness and diplomacy.

Along with the late Walter LaFeber, an American historian at Cornell, where Kagan taught in the 1960s, he was the best academic lecturer I have known. His lectures blended insight and the art of storytelling. His humor was rapid-fire, and he had a sense of timing that would have done a vaudevillian proud.

Yet, unlike most great lecturers, Kagan was equally at home in the seminar room. He prided himself on student-run seminars, in which he took a back seat. With weekly student papers shared in advance and assigned discussants to start the conversation, class was always lively and sometimes impassioned. Kagan often ended the session with a trademark “vote,” having the seminar vote on ancient matters of life or death like Thucydides’ Mytilenian debate or the trial of Socrates.

After graduate school, I stayed in touch with Kagan. He was generous enough to treat me as a friend. I last saw him this past June in Washington, D.C., when he was honored with an award from the government of Greece, which made him a Commander of the Order of the Phoenix in recognition of his achievement as a historian of Greek antiquity. The ceremony was followed by an outdoor dinner on the grounds of the Greek embassy. Kagan had aged, but he still had his sharp mind, his warmth, and his undiminished sense of realism. His two sons, Robert and Frederick, and their wives were there, all distinguished people in their own right, along with several of us former students. Kagan’s late wife, Myrna, a great lady, was missing.

At the dinner after the ceremony, I remember watching the sun go down. The occasion was bittersweet, but I felt overwhelmed with gratitude for my good fortune in having been not just a student but a friend of such an extraordinary man.

Barry Strauss is a military historian and classicist at Cornell University and the Corliss Page Dean Fellow at the Hoover Institution.