Remembering Tet

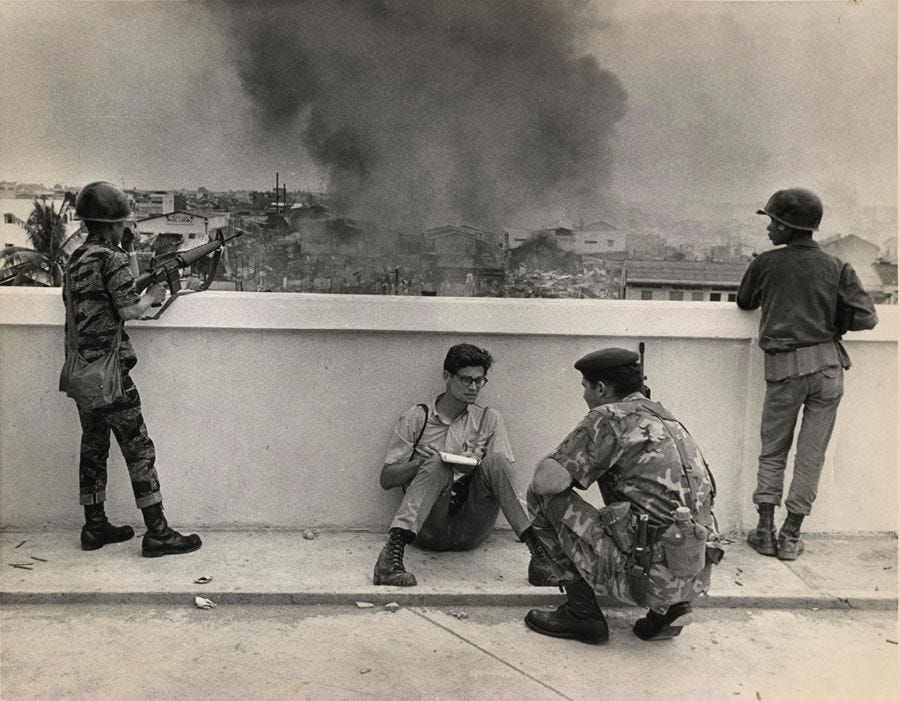

A reporter who was in Saigon recalls the day on January 30, 1968, when the South Vietnamese capital came under attack.

January 30 will mark the 53rd anniversary of the 1968 Tet Offensive, a series of coordinated Viet Cong and North Vietnamese attacks throughout South Vietnam. I was there.

One of the aims of the attacks was to spark a “general uprising” by the South Vietnamese people. Despite their taking place in some one hundred cities, provincial capitals, villages, and hamlets, they ultimately failed; the uprising never happened.

Another aim was to shatter the South Vietnamese Army. In this Tet also failed: The South Vietnamese fought better than their American advisers had expected. In Saigon they defeated the attackers within days, though fighting continued elsewhere. North Vietnamese leaders later allowed that they had overestimated their support in the South and grossly underestimated the strength and resilience of the South Vietnamese Army.

But a third goal was to shake American confidence in the war effort. In this Tet succeeded, with a large assist from America itself.

I was a foreign correspondent for eighteen years and covered the Vietnam War on and off for nine of them. The beginning of Tet is one of those things I’ll never get out of my head.

Tet is Lunar New Year in Vietnam. Its first day is the country’s biggest holiday. The two sides in the war had agreed to a truce to mark it. When I woke up that morning in Saigon, I thought I was hearing celebratory firecrackers.

But as I made my way to my office at UPI on the downtown waterfront, I realized that the sound was small-arms fire.

In later years, my family vacationed in Nags Head, North Carolina, where residents would set off fireworks each July 4. Everyone else would go outside to see them. I would stay in the house and wait until the noise was over.

Saigon had experienced grenade attacks and rocket attacks prior to Tet. In late June of 1965, a Viet Cong fighter had detonated two bombs that destroyed a restaurant just blocks from UPI’s office. But during the two years in which I’d been reporting on Vietnam, I’d never heard sustained shooting in the capital. I considered the place a safe haven.

It wasn’t anymore. The Communists had broken the truce and were assaulting locations throughout the South, including Saigon. We were under attack.

When I got to the office, the bureau chief and a bunch of reporters were sitting at their desks. The bureau chief was taking calls from field reporters and trying to reach U.S. officials to confirm the details of the attack on Saigon’s U.S. embassy. Two American soldiers suddenly appeared in the doorway. The Viet Cong had ambushed an American truck convoy while attacking the nearby South Vietnamese Navy headquarters. The soldiers, looking for safety, found our office. They threw themselves on the newsroom floor and shouted at us to get down and take cover. We were crazy if we didn’t; there was shooting going on nearby.

One of my jobs for the bureau in those days was to report on civilian casualties caused by Viet Cong rocket attacks on the city. The victims were invariably Vietnamese civilians, not soldiers. After one attack, which a historian later called the heaviest of the war, I drove into an area on the outskirts of the city in a UPI Mini Moke. It’s a type of vehicle that looks like a golf cart. It has no protective armor against shrapnel, so it’s not an ideal mode of transport in a war zone. When I arrived, I saw a good number of wounded civilians, mostly women. No ambulance had dared to enter the area.

So, I put away my notebook and started shuttling the wounded to ambulances. I have no memory of doing it, but a Vietnamese photographer working for UPI was with me. He snapped photos every step of the way.

It was one of the better things I did during my time in Vietnam.

In May the Viet Cong attacked Saigon again. During that attack, a Viet Cong officer shot and killed four unarmed Western journalists in the city’s Cholon district. I started carrying a pistol in my pocket. It was one of the stupidest things I did during the war. If I had been captured, the pistol would likely have signaled that I was a combatant. In turn, I would likely have been shot.

It didn’t happen. I was lucky.

Over the years, some accounts have argued that U.S. media reporting on Tet undermined American support for the war. In The Myths of Tet: The Most Misunderstood Event of the Vietnam War (2017), historian Edwin Moïse argues persuasively that this was not generally the case. But there was at least one high-profile exception: Walter Cronkite of CBS concluded that the war had reached a “stalemate.” His judgment affected the views of President Lyndon B. Johnson.

Moreover, the first reports of the attacks were alarming. Based on stories from the military police outside the U.S. embassy compound, news agencies initially reported that the guerrillas had penetrated the main embassy building itself. The Communists had planned that once the guerrillas had cut through the compound walls, a larger force of reinforcements would arrive. But the reinforcements didn’t get to Saigon in time. None of the guerrillas made it into the main building. The initial reports were later corrected, but the early television images of Viet Cong guerrillas on the grounds of the U.S. embassy shocked American viewers. Marine guards later killed most of the guerrillas (and captured three).

Even more important, in the months preceding Tet, General William Westmoreland, commander of U.S. forces in Vietnam, had repeatedly asserted that the United States was winning the war. It came as a shock to Americans to see the Communists displaying the ability to attack 36 of the South’s 44 provincial capitals, 5 major cities, 64 district capitals, and numerous villages and hamlets. The fighting that raged in Hue, Khe Sanh, and other locations throughout the South shook the Johnson Administration’s confidence, as well as that of many Americans.

And I still can’t stand the sound of firecrackers.

Dan Southerland served for more than five years as the Washington Post’s bureau chief in Beijing, as well as for nearly two decades as a foreign correspondent based in Tokyo, Saigon, and Hong Kong for UPI and the Christian Science Monitor. He retired in 2016 from his position as executive editor of Radio Free Asia.

Originally published January 29, 2021.