Self-Mastery Is Good, Actually

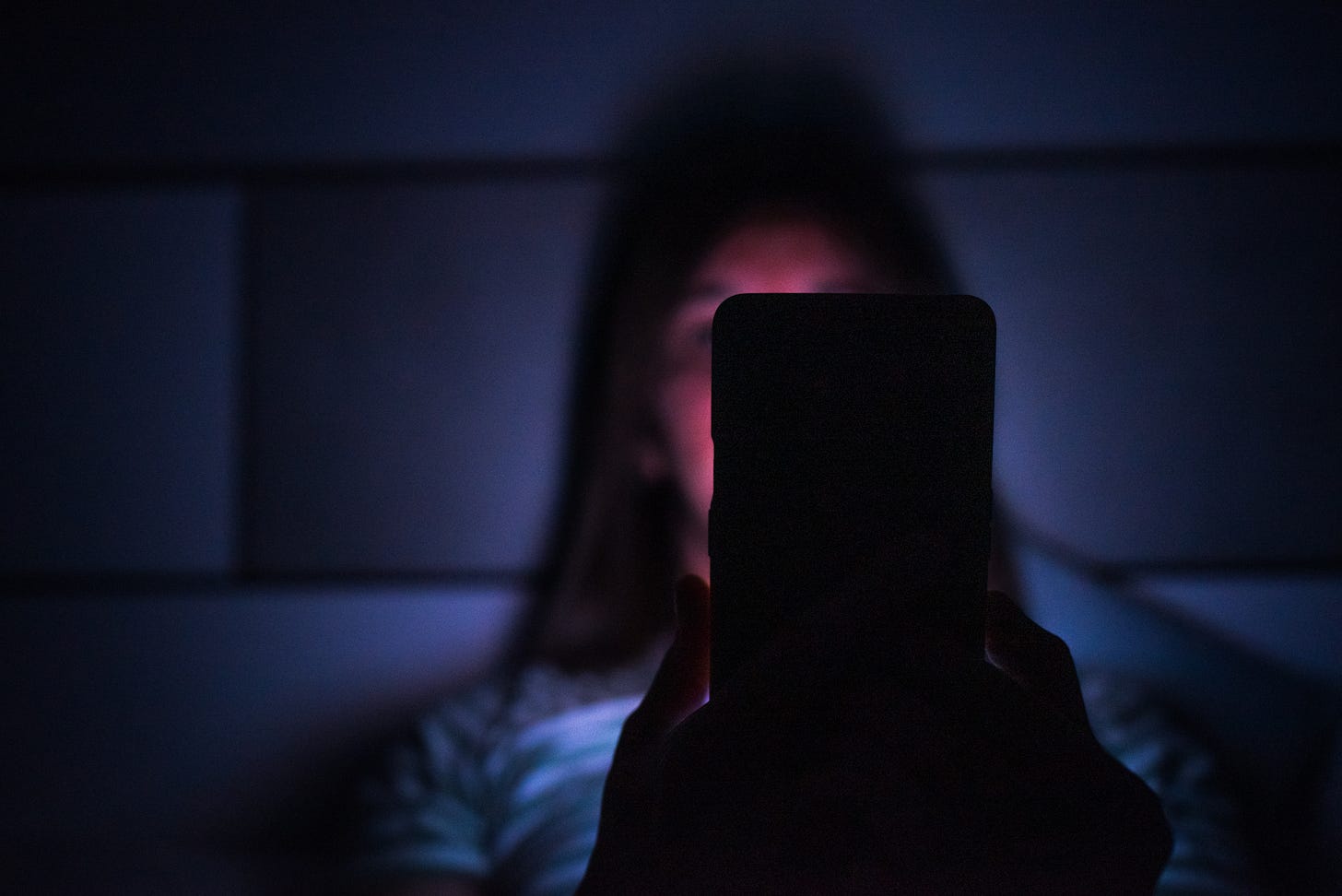

Social media is an addiction. We need to act like it.

Making intelligent and illuminating observations about cultural trends is tricky. It involves connecting seemingly disparate dots and transforming them into a coherent picture that isn’t initially apparent. But before that work of synthesis can happen, it’s first necessary to notice the dots in the first place. That’s hard for the same reason it would be hard for a fish to say something intelligent and illuminating about water: It’s everywhere; the fish is suspended within it, and it forms not just the background to its world but also permeates it from top to bottom.

I stumbled on one such cultural dot when I saw a post in The Argument by Jerusalem Demsas titled “I Could Watch TikTok for 10 Hours a Day.” Demsas didn’t make an entirely novel observation, but she expressed it well: Social media platforms are addictive. Those who spend hours a day interacting with them are addicts. Maybe when a friend reaches out to say he or she just spent five hours scrolling through Instagram, we should respond as if he or she just confessed to drinking an entire bottle of vodka alone on a Tuesday night—that is, with an expression of disapproval and an offer of help and support.

Demsas is open to entertaining the passage of new government regulations to address this problem, but as a young American living in the 2020s, she’s more comfortable thinking about how to “max out our nongovernmental powers.” By which she primarily means a technical fix analogous to the way GLP-1s successfully rewire brains to help people reduce their appetites and lose weight. As examples, she tells us she uses a “dumb phone” much of the time and leaves her iPhone at the office on weekends. She also suggests workplaces banning social media. And so forth.

Something about the way Demsas talks about this problem, which is very real, and the way she thinks to address it point to something else—something deeper and more troubling—that’s going on in our culture.

If It Feels Good, Do It

The political philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau observed that modern commercial societies have a way of conjuring desires for things that no one longed for in the first place. Supply isn’t always generated by pre-existing demand. Supply itself can generate demand. Ooh, just look at that shiny new thing! I’ve never seen anything like it before. It’s beautiful. It’s cool. It tastes great. It’s fun. It’s entertaining. It feels good. I want it. I need it.

Rousseau made his observation in the latter half of the 18th century. He saw the phenomenon quite early. It’s accelerated over the intervening two-and-a-half centuries, as a multitude of wondrous products have proliferated. Many of them have greatly improved our quality of life, making it easier, safer, and more enjoyable. They’ve “relieved man’s estate,” as Francis Bacon, an early modern theorist of technological modernity, memorably described one of its aspirations.

But somewhere along the way, mostly over the past couple of decades, capitalism has begun to do more than produce products. It’s begun to produce products that, in turn, produce experiences.

The experience of watching algorithmically curated, highly stimulating little video morsels, one after another, on a supercomputer we carry around with us in our pockets everywhere we go.

The experience, on those same devices, of easy gambling on sports and other competitive events.

The experience, on those same devices, of watching all-but-infinite amounts of every conceivable form of pornography.

The experience, soon to come on those same devices, of interacting with artificial intelligence capable of producing an incredibly realistic simulacrum of a romantic and erotic partner.

The experience of joining together with ideologically likeminded compatriots anywhere in the country and the world to do battle against political opponents and enemies. (Yes, it’s likely that a number of our political problems can be traced back to the transformation of political activity into one more mode of digitally mediated experience.)

These kinds of experiences, which create an incredibly intense link between a person’s mind and an online interactive social world of human and artificial forms of intelligence, can be incredibly addictive, precisely because they feel so real and, lacking the friction and complications of real-world physical interactions, are so psychically intense. Cognitive scientists and social psychologists are inclined to describe these experiences in terms of chemicals released in the body: we’re getting addicted to dopamine and serotonin and adrenaline.

However true that might be at the level of physiology, I prefer to think about it in the less reductive, old-fashioned moral categories that come down to us from the tradition of political philosophy: Digital technology is giving us incredibly intense experiences of pleasure; pleasure is a powerful temptation that is extremely difficult to resist; what we often call “addiction” is more accurately described as an incapacity to achieve self-mastery sufficient to resist the siren song of pleasure.

Resisting Temptation in a World Lacking Support for Virtue

It is darkly ironic (or perhaps extremely significant at a deep cultural level) that human beings began producing technologies capable of generating such intensely pleasurable experiences less than half a century following a decade (the 1960s) when countries around the world underwent a cultural revolution that began disassembling the complex social and ideational mechanisms that humanity long used to fortify the capacity of individuals to resist powerful temptations. Tired of feeling judged—by God, by parents, by neighbors, by our own consciences—we rebelled, proclaiming before all the world that what we choose to do with our lives is a matter of moral indifference and no one’s concern, maybe not even our own. (French novelist Michel Houellebecq is our greatest imaginative explorer of this post-’60s terrain and its myriad discontents.)

This shift has left each of us to our own devices—quite literally, it would seem. Like Demsas, most of us would rather avoid asking the government to step into the role of an objectified Superego telling us what to do. But neither do we feel capable of straightforwardly resisting temptation on our own. We can’t stop ourselves from eating a pint of ice cream or a bag of Doritos in front of the computer, but we can ask our doctor for an Ozempic prescription and then take the proper dosage. We can’t resist spending hours on TikTok or Pornhub every evening, but we can choose to leave our phones or laptops at the office so we won’t. We have will power, but we also lack sufficient will power. We can ask for help, but we can’t fully help ourselves.

Maybe there’s nothing wrong with this. Gluttony—for food, for drink, for sex, for pleasures of every variety—has long been considered a vice and a sin. In attempting to resist or moderate it, we used to rely on belief systems and a thick set of institutions and social relationships that, for many of us, no longer exists. Because of their disappearance, we instead reach for pharmacological helpmeets or little cognitive-behavioral tricks to keep us from giving into our intensely pleasurable addictions. Whatever gets you through the night.

The End of Self-Mastery

Yet I can’t help but wonder if there’s a loss involved in relying on these helpmeets and tricks instead of the old beliefs, institutions, and social relationships that existed to encourage and support individuals attempting to do the hard part for themselves.

It’s the difference between leaving your iPhone at work and bringing it home but mastering your desire to use it more than you think you should. Or between taking a GLP-1 and choosing not to but saying no to the dessert anyway, even though you want it, because you know saying yes will be bad for you and that knowledge is good enough to get you to act according to a higher notion of your own self-interest.

When we rely on a machine to do an arduous physical task for us, we avoid injury and get to enjoy greater leisure. But what if it’s physically and spiritually healthier to complete the task for ourselves, with our own hands and arms and legs? Our own muscle and bone?

Human beings are weak, needy creatures. We require encouragement and support in doing what we know is good. And yet we’ve created a world of unprecedented temptations at a moment in history when our old support systems have been dismantled. That might make helpmeets and tricks the best most of us can do.

I hope it’s enough—but I worry it won’t be. Self-mastery is good and important. And I’m not sure we’ve thought long or deeply enough about what it would be like to live in a world without it.

Damon Linker writes the Substack newsletter “Notes from the Middleground.” He is a senior lecturer in the Department of Political Science at the University of Pennsylvania and a senior fellow in the Open Society Project at the Niskanen Center.

A version of this piece originally appeared in Notes from the Middleground.

Follow Persuasion on Twitter, LinkedIn, and YouTube to keep up with our latest articles, podcasts, and events, as well as updates from excellent writers across our network.

And, to receive pieces like this in your inbox and support our work, subscribe below:

This is about prosocial versus antisocial bonding. As humans, we almost all need bonding. And if we can't get prosocial bonding we'll settle for antisocial bonding. Sobriety works when it works, when there are prosocial bonding alternatives to drinking. Most alcoholics discontinue problematic drinking not because they enter recovery, but because they end up in friendships or a romantic relationship with someone who is not an alcoholic and are thus engaged in prosocial bonding activities that outcompete the antisocial chemical-bonding of intoxication. It's the really recalcitrant alcoholics that end up in treatment because they've continued to engage in problematic drinking no matter the prosocial bonding alternatives. Heyman's "Addiction: A Disorder of Choice," is a great resource on this. But like you say, the challenge with social media and digital life in general, is that many quotidian prosocial bonding alternatives are largely gone. Or wherever they remain, they are gatekept by the antisocial digital world. Or just cannot outcompete the ease and instant chemical-bonding reward of the antisocial digital world. Like all addiction, we can't overcome it alone. Rather, with the help of others, we have to find ways to fill our time with prosocial alternatives.

Great article and concept of lack of self mastery/composure. I recently finished Jeffrey Rosen's excellent book, the Pursuit of Happiness. The founders correctly viewed the Pursuit of Happiness as the pursuit of personal virtue and self mastery, the only lasting source of true happiness. That understanding has been diminished post 19060s as you reference. Again, great piece.