Seven Days of War

David French, Sheri Berman, Edward Luce, Moisés Naím, Denise Dresser, and Persuasion editors analyze Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

Edward Luce: The Democratic World is Beginning to Rally

February 24, 2022—like 9/11 and the fall of the Berlin Wall on November 9, 1989—will go down in history as the day an era ended. On Thursday last week, Putin obliterated what remains of the post-Cold War era, and with it what some people still call the liberal international order. War is a dark force that can also bring out the best in the human spirit. Thus February 24 also conjured the incandescent spirit of Volodymyr Zelensky, a man who nobody could have guessed a few days earlier would turn into such an inspiring symbol of democratic resistance.

If there is a silver lining to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, it is the popular outpourings such images have elicited across the world, but particularly within the West's self-doubting liberal democracies. Our response, appropriately enough, has been led from below—the soccer crowds waving Ukrainian flags, the mass demonstrations in Germany, and the welcoming of hundreds of thousands of Ukrainian refugees. Putin’s barbarism has brought out the opposite of what he intended—a united Europe, a new spirit of democratic solidarity, and of course a public revulsion about what Putin could do. If this spirit takes root, February 24 might also be remembered as the point when the democratic world began to regroup.

Edward Luce is the U.S. national editor and columnist at the Financial Times and an advisor at Persuasion.

Martin Eiermann: The Human Costs of Geopolitical Calculus

When I was little, it was not uncommon in rural Germany to see old men with a missing leg or arm. As a child, I considered this a natural part of the aging process: One adds years and loses limbs. I cannot remember when some well-meaning adult informed me that these were, in fact, the lifelong scars of World War II. But I do remember what it was like to grow up amidst the perpetrators and survivors of that war.

One of my grandfathers had been drafted at age 19 from his apprenticeship as a blacksmith into the Wehrmacht and sent to the Eastern Front, where he helped to hunt down anti-fascist resistance fighters before he was captured by the Red Army and sent off to a Soviet labor camp.

My other grandfather was too young to fight. He experienced World War II as carpet bombing, barefoot escapes from burning rubble, starvation, and boys being rushed to the front in a last-ditch effort by the Nazis to stop the Allied advance. He recently passed away after years of physical and cognitive decline. But as his strength waned, the memories became more vivid. We had to replace his refrigerator, because the humming sound reminded him of the engines of bombers flying overhead and caused him to wake up in panic. He could not watch TV coverage of the wars in Syria or Afghanistan, because the plight of the refugees reminded him too much of his own. He was not even a teenager when World War II ended, yet it cast a shadow over the remainder of his life.

Do not resist the comparison to Ukraine today: Russia’s war of aggression is not just a tragedy in the singular and the abstract—geopolitically, economically, et cetera—but a conglomeration of countless individual tragedies. For some, the experiences of state-sponsored violence will become first memories. For others, they will mark a moment when life was irrevocably altered. The scars of this war will remain for a lifetime. This is why solidarity with Ukraine is not just a defense of general principles but of concrete human flourishing—of protecting people from the experience of war and delusions of imperial grandeur, however imperfectly. It is not surprising that all attempts at equivocation ignore the human toll of this war, either by emphasizing Russia's abstract “legitimate interests” in Ukraine or by weighing Putin’s invasion against previous American wars. But this, too, is a lesson from the twentieth century: When the suffering of people disappears from the political calculus, liberalism has lost.

Martin Eiermann is a sociologist and contributing editor at Persuasion.

David French: Miscalculation on Both Sides

After seven days of intense conflict in Ukraine, a consensus has emerged, even while the battlefields are still shrouded by the fog of war: Putin miscalculated. He planned for a lightning campaign. He planned for a decapitation strike. Instead, he got a slugfest, at least so far.

The common explanation for Putin’s miscalculation is the one that lets the West off the hook—dictators are surrounded by “yes men.” They tell the leader what he wants to hear. We blame his failure on his blindness. That’s surely part of the story, but there’s another part, one that’s common to history. The dictator thought he’d succeed because he’d succeeded many times before. In 2000, he turns Grozny in Chechnya to the “most destroyed city on earth,” and the West shrugs. In 2008, he invades Georgia, the West protests, but Putin still wins. In 2014, Russia snatches Crimea from Ukraine and launches the ongoing war in the Donbas. The West sanctions Russia, but Russia wins again. In 2015, Putin intervenes in Syria, and some in the West laughed, claiming that he bought himself a quagmire. Yet his scorched-earth tactics work, he stabilizes the Assad regime, and he wins once more.

How many times must we endure the same cycles? A powerful country reaches and reaches and reaches, right until the moment of overreach. Perhaps these cycles are inevitable. Liberal democracies crave peace and stability. They’re hesitant to escalate. They’ll see conflict as manageable and containable, right until the moment that it’s not. By then it’s too late to spare the world from the death and suffering we are witnessing today.

But this much we do know—those nations in NATO’s defensive alliance are untouched. Their security is guaranteed. If Putin sought to undermine their mutual commitments, he compounded his military miscalculation with a grave diplomatic error. He taught the democracies of the world that their safety depends on their solidarity, and he now faces a revived West.

That’s cold comfort, however, to Ukrainians who stand alone, fighting for every inch of their nation against overwhelming force. Western solidarity did not extend far enough, fast enough. And now they pay the ultimate price.

David French is a Senior Editor at The Dispatch, a veteran of the Iraq War, and an advisor at Persuasion.

Sheri Berman: Those on America’s Extremes See What They Want in Ukraine

An old adage holds that “crises don’t create character; they reveal it.” This surely fits the far left and far right today. The Ukraine crisis has revealed both to be reactionary: motivated by “reflexive opposition” to what they oppose, rather than “first principles or reason” and a vast inflation “of the threat of what they oppose, driving responses disproportionate to the scale of the harms they critique.”

On the far left this takes the form of reflexive anti-Americanism. The Ukraine crisis, in this view, is the fault of the United States, which threatened Russia via “NATO’s expansionist drive.” Putting aside his trampling of innumerable international agreements regarding Ukrainian sovereignty as well as the question of how much notional NATO membership mattered to Putin, this is a bizarre argument for the left to make. It rests upon assumptions they normally passionately reject: namely that big, powerful countries, like Russia, are entitled to “spheres of influence” while smaller, less powerful countries, like Ukraine, are not entitled to determine their own political alliances and fates. The left’s anti-Americanism has led to an embrace of an “anti-imperialism of idiots”: one equating imperialism only with the actions of the United States while ignoring or excusing similar actions committed by America’s opponents.

On the far right, admiration of Putin and sympathy for his invasion of Ukraine reflect the grievance politics at the heart of Trumpist Republicanism. Trump has long praised Putin and over the past weeks the number of right-wing politicians and commentators jumping on the Putin bandwagon has grown. Stephen K. Bannon, for example, extolled Putin for being “anti-woke” while Tucker Carlson urged his viewers to “think about” why Democrats “want you to hate Putin,” reminding them that the real enemy is those “who want to teach your kids to embrace racial discrimination.” The far right’s culture war obsessions and hysterical hatred of Democrats has led to an embrace of an “enemy of my enemy is my friend” politics antithetical to traditional Republican concerns for protecting America’s national interests.

Sheri Berman is a professor of political science at Barnard College, Columbia University, and an advisor at Persuasion.

Moisés Naím: Two Existential Threats, Not One

The bravery of the Ukrainian people and their initial effectiveness at resisting the Russian invasion were as unexpected as the attackers’ fumbling. Even more surprising was the alacrity with which the world’s democracies shifted long-held policies to face up to the new threat.

By coincidence, four days after Putin’s invasion, a panel of the world’s most prominent climate scientists released a landmark report showing the world faces another threat that is just as dire. Drawing on thousands of scientific studies, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) found that the human cost of extreme weather events driven by global warming is at an all-time high. Up to 14% of land species could vanish in a 1.5ºC. warming scenario, and that scenario is looking increasingly out of reach. Hunger will worsen, especially in already-hungry areas. New diseases will spread as food spoils, water becomes tainted, and mosquitoes extend their habitat. And it’s all happening much faster than the most pessimistic scenarios foresaw just a few years back.

In a more rational world, world leaders would have reacted to the IPCC report the way Germany’s leaders reacted to the invasion of Ukraine: quickly abandoning dead ideas and rapidly shifting to a drastically new policy stance aligned with the realities of the twenty-first century. On balance of probability, our drastically changing climate poses a danger on at least the same order of magnitude as Putin’s Ukrainian thuggery and nuclear threats.

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine is an unspeakable crime, and a heartbreaking tragedy. The silver lining is that the world’s democracies showed that, faced with an existential threat, policy can change decisively, and fast. It’s time they took that newfound superpower and applied it to the second of our existential crises, too.

Moisés Naím is a Distinguished Fellow at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, and an advisor at Persuasion.

Martin Eiermann (2): Germany’s Pivot

It speaks to the swiftness of Germany’s foreign policy pivot that even close political allies of Chancellor Olaf Scholz found out about the proposed initiatives only when he announced them during a special parliamentary session on February 27. Germany will not utilize the Nord Stream 2 pipeline (already built and almost ready to operate); it will deliver lethal arms to Ukraine; it will set aside 100 billion Euros for a special defense fund; and it will amend the country's constitution to secure increased military spending in the long run.

Collectively, these policies mark the end of two long-standing themes of German foreign policy: First, a profound uneasiness about the use of German military force and technology, especially on European soil. Second, an active engagement with Russia under the “change through rapprochement” doctrine that dates back to the 1960s but continued to shape Berlin's relationship with Moscow until this year.

The current pivot is not just a response to the war of aggression and the humanitarian tragedy unfolding in Ukraine. It also proclaims that geopolitical roles defined during the twentieth century may prove to be inadequate in the twenty-first.

David Hamburger: Keeping the Faith

It is increasingly clear that Putin, frustrated by his miscalculation after years of Western complacency and implacable in his delusion, will be willing to turn Ukraine into a European Syria, another Chechnya.

How will we respond? This is a question of months and years, not the last seven days. There is much to be praised in the swiftness and unity of the global response thus far. It is indeed heartening to see stirrings of vigor in defense of what seemed a sclerotic liberal democratic order. But this “silver lining” also shows us plainly the stakes of the coming long challenge.

There is a real risk that, even as Ukrainians remind us what sacrifice for democracy means, our initial unity turns increasingly to disillusionment at its apparent inability to prevent further atrocities. Ukraine’s place as a frontline of democracy thus has a double significance: If that line does not hold, it is not only that dictators will be emboldened. It is that our own faith will founder. Failure will not only mean the abandonment of the Ukrainian people and, in cold geopolitical calculus, a strategic loss in the battle to contain Putin's revanchism. If, despite our actions, we fail to arrest the carnage, our newly-renewed spirit may prove another casualty. That recognition should spur policymakers and the public alike to prepare for the long haul.

David Hamburger is executive director at Persuasion.

Denise Dresser: Next Steps for the Anti-Putin Alliance

Putin has long been sowing the seeds of polarization and discord across the globe. Yet the warning signs were frequently dismissed as crying wolf. Now the wolf has attacked, and suddenly the West is realizing what is at stake: The future of democracy, the stability of Europe, the survival of liberalism as an aspiration to be fully realized. Jolted out of its complacency, the West appears to be responding with a remarkable display of unity and coordination.

If the world is to become safer for democracy, these encouraging signs must be consolidated through the further isolation and ostracism of Putin. He must become an international pariah, and this can be achieved by heightening sanctions, freezing assets, exposing oligarchs, gravitating towards renewable energy sources, strengthening the European Union and showing China the cost of emulating Putin’s playbook in Taiwan.

Yet the immediate imperative must be to assure the survival of an autonomous and democratic Ukraine. Even if Putin is stopped, toppled or contained, the West will have learned its lesson the hard way: that democracy must be defended early on, and warning signs must be taken seriously.

Enough of strongmen violating democratic norms, dismantling democratic institutions, and producing polarized politics that enable the entrenchment of authoritarian populists. If there is a silver lining to the cloud that has darkened Ukraine and Europe, it must be this: Global tolerance for autocrats and bullies has come to an end. And the international community can and will unite to assure that attempts to replicate the Putin model are thwarted.

Denise Dresser is a professor of political science at the Instituto Tecnológico Autónomo de México, and an advisor at Persuasion.

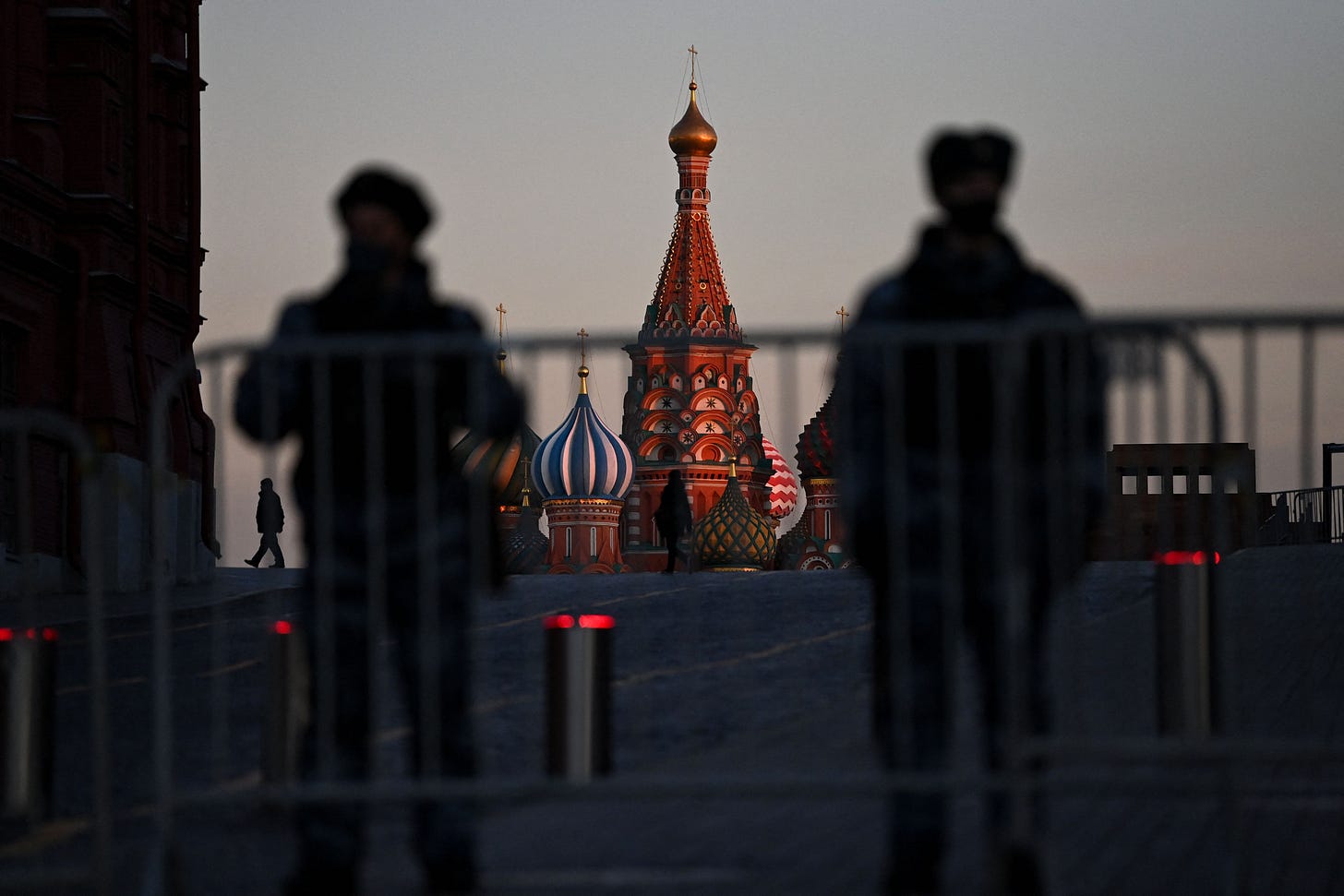

Photo Credits: Flag (Getty Images); Red Square (Kirill Kudryavtsev/AFP); Carlson (Chip Somodevilla/Getty Images); Scholtz (Keuenhof-Pool/Getty Images); State of the Union (Photo by Mario Tama/Getty Images); Putin (Mikhail Klimentyev/Sputnik/AFP)

In response to Martin Eiermann, I can relate that my mother spent The Blitz in London, and never got over her terror of low-flying planes (or, for a long time, of flying at all). At least a couple of times I saw her stop herself from jumping under a table when something flew overhead a little too low--and this was in the 1970's. The 'PTSD' often doesn't go away, especially when not dealt with.

One of the worst Persuasion posts I've ever read. Unanimity of opinion, all in favor of framing the matter as a childish morality tale, with emotional appeals based on who supposedly "cares" and "doesn't care."