Sometimes You Get Another Chance

Donald Trump took us out of the Democracy Business. This is the time to get back in. The second in a series of three articles from the author’s forthcoming book.

Throughout his decades of public service—as senator, vice president, presidential candidate, and President-elect—Joe Biden has demonstrated his commitment to defending human rights and supporting democratic values in the conduct of American foreign policy. Therefore, one can confidently predict that he won’t check his values at the door before meeting with foreign leaders such as Russian President Vladimir Putin. In fact, I can do more than predict; I was in the room the last time they met, in Moscow in 2011.

Biden will also engage directly with not just government leaders, but pro-democratic civil society activists, as he did when we traveled to Georgia, Moldova, Russia, and Ukraine during the Obama Administration.

___STEADY_PAYWALL___

Third, the Biden Administration will not take democratic allies for granted. They are our most reliable and enduring international partners; the new administration will seek ways to deepen our ideological affinities and security commitments with them.

Fourth, Biden and his team clearly understand the value of engaging multilateral institutions to advance American interests, norms, and values. The Trump Withdrawal Doctrine will soon end. Biden has already committed to organizing and hosting a global Summit for Democracy to “renew the sprit and shared purpose of the nations of the Free World.” Convening such a meeting in the first year of the Biden Administration will be an important action-forcing event, which will compel the U.S. government to think more systematically about why and how the United States should advance democracy abroad. As the author of Advancing Democracy Abroad: Why We Should and How We Can, I am thrilled.

Yet a decade after that 2010 book, many of its ideas have not been implemented or even pursued. I was told that they were too ambitious; the timing was not right; or we needed, after President George W. Bush’s Freedom Agenda, a return to more “pragmatic realism.” Wars in Afghanistan and Iraq led many to conflate democracy promotion with military intervention. Labels like “neocons” and “liberal interventionists” became cartoonish memes. While the Obama Administration made some incremental progress on the agenda, Trump mostly shut it down.

Biden’s election provides new hope. Because of Trump’s disdain for supporting democracy abroad, the rise of autocratic China and Russia, and a 14-year global democratic recession, conditions are ripe for a bold American initiative to support democratic ideas around the world. “Small d” democrats around the world, whether ministers in democratic governments or activists fighting autocratic regimes, yearn for renewed American leadership. Biden has a real chance to think and act boldly, especially in reorganizing U.S. support for liberal ideas and democratic governance abroad and in cooperating with democratic allies to reinvigorate a global movement for democracy.

Biden and his team need to avoid small ball—a new deputy national security advisor here, a new Executive Order there—and seize this moment.

The Moral and Pragmatic Case

Democracy is a more moral system of government than all others. It provides more of the conditions for positive welfare outcomes, including economic development, better health, improved education, and less violence against citizens. Nor, contrary to past wisdom, do democratic transitions trigger negative economic outcomes; on average, it is just the opposite. In contrast to dictatorships, modern democracies prevent leaders from pursuing the most egregious policies, like famine and genocide. Finally, most people around the world prefer democracy to other forms of government. Thus, there are many moral reasons why the Biden Administration, U.S. Congress, and American society in general should support democracy, human rights, and the rule of law around the world.

There are also pragmatic, realpolitik reasons for the United States to advance this agenda. Most important, the global spread of democracy makes Americans more secure at home. Only dictatorships, never democracies, have attacked the United States. Not every autocracy is or has been an enemy of the United States, but every enemy of America is or has been an autocracy.

The deadly cocktail of autocracy plus power has always threatened American security, be it with World War I, World II, the Cold War, or China and Russia today. Likewise, illiberal transnational organizations have carried out terrorist attacks against Americans; pro-democratic groups have not. Past transitions from dictatorships to democracies have usually enhanced American security, creating new allies in Germany, Italy, and Japan after World War II and throughout Eastern Europe after the Cold War. U.S. relations with Russia improved after democratic changes in the 1990s and worsened as Putin became more autocratic over the past two decades. China’s pivot towards greater autocracy under President Xi Jinping has correlated with greater tensions in U.S.-Chinese relations. Today, theocratic Iran and the personal dictatorship in North Korea threaten American security.

That the United States benefits from more democracy in the world does not mean that American leaders today have the ideas or means to promote democracy abroad. After fourteen years of democratic recession worldwide, we should be humble in our proclamations and ambitions. Successful strategies from the past may not work in the future. We have work to do in order to get better in this endeavor—at home, in the conduct of our foreign policy, and in our cooperation with democratic allies.

During the Cold War, American government leaders invested heavily in new instruments of soft power to contain communist ideas and promote democratic values (albeit often ignoring repressive dictatorships allied with us against the Soviet Union). Public broadcasters like Voice of America and Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, by providing news and pro-democratic commentary to individuals in communist countries, paved the way for newer broadcasting stations such as Radio y Televisión Martí (Cuba), Alhurra (the Middle East and North Africa), Radio Sawa (the Middle East), and Radio Free Asia. President John F. Kennedy established the Peace Corps, the Alliance for Progress, and the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID). President Ronald Reagan created the National Endowment for Democracy and its affiliated organizations: the National Democratic Institute (NDI), the International Republican Institute (IRI), the Center for Independent Private Enterprise (CIPE), and the American Center for International Labor Solidarity (the Solidarity Center). Even more so after the collapse of communism, other non-governmental organizations (NGOs)—including the International Foundation for Elections Systems, Freedom House, Internews, IREX, the Asia Foundation, the Eurasia Foundation, the Carter Center, and the Open Society Institute—played an expanding role in promoting democratic ideas and practices abroad.

In the post-Cold War era, the U.S. government added new instruments to promote accountable government, democracy, and human rights. The State Department’s Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor expanded. President George W. Bush launched the Middle East Partnership Initiative (MEPI) and Millennium Challenge Corporation (MCC). There have been several democratic breakthroughs in the past three decades—Serbia (2000), Georgia (2003), Ukraine (2004 and 2014), Tunisia (2011), Malawi (2017), and Armenia (2018). In the margins, American actors have helped some of them to occur. And global demand for democracy and accountable government remains strong. Almost always where democratic activists are fighting against autocratic regimes, they seek American support, at least rhetorically if not directly.

Yet American policies and programs also have had major setbacks in the post-Cold War era. Most damaging, U.S. efforts in Iraq and Afghanistan, after decades of deaths and trillions spent, produced limited results and created the misimpression that U.S. democracy promotion was intertwined with military intervention. Consolidation of democracy after U.S. military intervention has rarely worked; we are four for seventeen (five for eighteen if you count tiny Grenada) since our first attempt in the Philippines in 1898 after the Spanish-American War. U.S. efforts to assist pro-democratic Arab uprisings achieved limited results and, in Libya and Syria, tragic outcomes. The United States has accomplished little in trying to reverse increased repression in Bahrain, China, Iran, North Korea, Russia, Saudi Arabia, Turkey, Venezuela, and Vietnam. During the Trump era, the United States did not even try, except in Venezuela and maybe a little bit in Iran; both efforts failed.

Setbacks in democracy promotion have persuaded some that the mission should be abandoned entirely. President Donald Trump showed almost no interest in this agenda, but progressive politicians and organizations have also retreated from this mission, urging instead that the United States get its own house in order. Renewing American democracy at home is indeed essential to revitalizing it abroad, but we can pursue both at once. Recalibration, not retreat, is the answer.

Renewing American Democracy

We cannot compete effectively with China and Russia around the world until we renew and strengthen our democracy at home. Almost everyone agrees that the Biden Administration’s work with partners in Congress and the broader society to strengthen American democracy is necessary if we are to have credibility in advancing liberal democratic values abroad. The logic is obvious: We cannot convince others to become more democratic as we gradually become less so. Freedom House assessed the United States in its comparative rankings of global political systems in these terms:

The United States is a federal republic whose people benefit from a vibrant political system, a strong rule-of-law tradition, robust freedoms of expression and religious belief, and a wide array of other civil liberties. However, in recent years its democratic institutions have suffered erosion, as reflected in partisan manipulation of the electoral process, bias and dysfunction in the criminal justice system, flawed new policies on immigration and asylum seekers, and growing disparities in wealth, economic opportunity, and political influence.

According to Freedom House, U.S. democracy has fallen below comparative systems in Europe, Australia, and Canada. The Economist’s Democracy Index places the United States below two dozen other democracies, while the Varieties of Democracy Index has tracked a substantial erosion of democratic practices and rising autocratic features in the American political system.

In theory, the list of democratic reforms that a Biden Administration should pursue is clear. Larry Diamond’s 2020 book Ill Winds provides a clear roadmap. So does H.R. 1, the For the People Act of 2019, passed by the U.S. House, which seeks to “expand Americans’ access to the ballot box, reduce the influence of big money in politics, and strengthen ethics rules for public servants,” as well as S. 4263, the John Lewis Voting Rights Advancement Act and the subsequent H.R. 8363, the Protecting Our Democracy Act.

A longer list of reforms should include even greater transparency regarding campaign financing, lobbying, and beneficial ownership of limited liability companies, corporations, and even real estate. A more ambitious agenda could include the end of partisan redistricting, changes to the electoral laws to increase representation and accountability such as ranked-choice voting (RCV), major immigration reform, serious changes in the laws and norms guiding policing, new regulation of social media platforms, statehood for Washington, D.C., and retirement of the Electoral College. (As a former U.S. ambassador, I can testify that it is impossible to defend the Electoral College as a democratic institution to foreigners.)

In practice, however, Biden is unlikely to make much immediate progress on this list, especially if the Republican Party retains control of the U.S. Senate. He can and should use Executive Orders to roll back Trump’s most anti-democratic, illiberal policies on immigration and travel bans. But the project of democratic renewal in the United States will stretch years, if not decades, into the future. Biden cannot wait until American democracy has been thoroughly rejuvenated before seeking to defend and advance democracy abroad.

A New Biden Doctrine

While Biden is constrained in strengthening American democracy at home, he has more freedom in foreign policy. His administration must first articulate a new vision for supporting democracy abroad, hopefully spelled out in his 2021 National Security Strategy, fundamentally reform the way the U.S. government supports the vision, and then work with allies to internationalize the project of democracy promotion.

Regarding new policy and doctrine, consolidating recent democratic gains in the world must become Biden’s top priority. Defense, not offense, is the order of the day. After countries experience peaceful democratic breakthroughs, the U.S. government and NGOs have more effective tools, greater leverage, and more committed local allies to aid democratic consolidation. Transitional moments provide the greatest opportunities for real change. They are the rare, limited periods when new democratic leaders and their governments most welcome assistance. The U.S. government should concentrate its limited resources on these breakthrough countries instead of spreading these resources thin to every country in the world, or aiding autocratic or semi-autocratic governments in the quixotic hope that they will gradually democratize.

The Biden Administration should establish a special “democracy dividend” fund that could provide immediate new resources to new leaders who come to power after democratic breakthroughs. USAID’s Office of Transition Initiatives should be vastly expanded and include more “reservist” democratic experts outside of government to be deployed to countries immediately after the collapse of dictatorships. (We could have used such a fund and such experts when the Arab Spring unexpectedly erupted in 2011.) Today, in countries like Tunisia, Armenia, Sudan, and Ukraine, the United States should invest heavily in consolidating recent progress. In his analysis of democratic breakthroughs or “electoral earthquakes” from 2009 to 2020, Larry Diamond concludes that “only two of the 20 cases have so far resulted in democratic transitions.” And yet, Tunisia and Ukraine are not yet consolidated democracies, and therefore should receive much more focused attention from U.S. government programs and American NGOs.

Second, the Biden Administration must devote greater effort to preventing backsliding and encourage a return to democracy by allies like Hungary, Turkey, Poland, India, and South Korea. This will be hard, especially given our recent democratic backsliding in the United States. Nonetheless, President Joe Biden, Vice President Kamala Harris, cabinet secretaries, and ambassadors must signal clearly and speak out explicitly about why we place democratic values at the core of our bilateral relations. There can be no more indifference to dangerous autocratic trends, no more avoiding sensitive topics to have a “good bilat.” More ambitiously, President Biden could provide leadership for rewriting the NATO charter to allow for the suspension and even expulsion of member states that fail to meet basic commitments to democracy and human rights.

Third, the Biden Administration should end the practice of providing direct assistance to NGOs in autocracies. The State Department should not be directly funding civil society organizations in Russia, China, Iran, Cuba, Venezuela, Saudi Arabia, or North Korea. That strategy sometimes worked in the past but is counterproductive and nearly impossible today: Aid recipients are quickly labeled enemies of the people and American agents, and those willing to take such funds sometimes lack domestic legitimacy. Instead, as discussed below, other foundations not directly tied or controlled by the U.S. government should fund civil society activists abroad. Hostile autocratic regimes will still brand their domestic democratic challengers for taking foreign aid, but separation between the U.S. government and civil society actors will make the labels less sticky.

Fourth, President Biden and his administration must commit to playing the long game of democracy promotion by investing in policies and programs whose payoffs will not be realized for decades. Ideas matter. Education matters. Greater resources should be devoted to educational programs that provide information about democracy, the rule of law, and liberalism more generally as well as to exchange programs that bring students and visitors from autocratic countries to the United States. Internships in the United States that promote entrepreneurship should be expanded. In the 1990s, the U.S. government supported too many democracy “technical assistance programs” benefiting government elites and not enough civic education projects, new university courses on democracy, or translations of books and articles about democracy. (For instance, every issue of the Journal of Democracy should be translated into multiple languages and made available free online.)

Fifth, President Biden should state explicitly as a matter of policy in his 2021 National Security Strategy that the United States will not use military intervention to promote democratic regime change. The truth is that American presidents have almost never invoked democracy promotion as a justification for war; the U.S. military interventions in Grenada and Panama may be the only exceptions. Even before the invasion of Iraq, President Bush and his administration focused primarily on security threats like Saddam Hussein’s alleged weapons of mass destruction. Only after intervention and occupation have American presidents pivoted to democracy building. We have rarely invaded a country to promote democracy, but have also infrequently exited without attempting to leave a democratic regime behind—usually with poor results. Therefore, Biden should make his intentions clear; making a credible commitment to avoiding such wars is also prudent for keeping the United States committed to more salient national security objectives. To compete with China and Russia in the 21st century, U.S. decision-makers must avoid ambitious, distracting projects like building democracies in countries that are at war or occupied by American soldiers.

Sixth, our record on using economic sanctions to undermine autocracies and spark democratic change is also very thin. Sanctions should be used to punish dictatorships and change bad behavior, but should only be used for regime change in the very rare case when democratic forces inside the oppressive regimes explicitly call for the United States and other democracies to pursue this approach, as in the case of apartheid South Africa. The Biden Administration should state explicitly that sanctions will be deployed to change the behavior of states, not to undermine them.

Seventh, the administration should state explicitly that values will be a component of every bilateral relationship, especially with autocracies. Leaders in Beijing, Moscow, Tehran, and Pyongyang, but also Riyadh, Rabat, Amman, and Hanoi, must know that democracy, human rights, and the rule of law should be expected topics of any government-to-government meeting. President Biden should revitalize the dual track diplomacy—engaging both government and societies—he practiced as senator and vice president.

Reorganization

During the Cold War, the United States developed extensive international aid and development programs to help contain communism. It is no accident that Kennedy founded USAID in 1961 at the height of the Cold War. USAID, in turn, played a central role in promoting American soft power. U.S. government development assistance is now institutionalized on a global scale, providing technical assistance led by in-country resident offices supplemented by substantial financial assistance. We currently support USAID missions with development experts in roughly seventy countries.

To keep pace with our autocratic competitors today, especially China, American global assistance efforts require more resources, more strategic thinking, and serious restructuring.

In the past two decades, China has launched many new assistance programs and international organizations to expand its influence, including most prominently the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank, the Belt and Road Initiative, the Cross-Border Interbank Payment System, an expansion of fintech, and a digital yuan. We have fallen behind. Kennedy’s 1961 Foreign Assistance Act has never been fundamentally updated.

The Bush Administration achieved some reform success, including the creation of the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief and the MCC. Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice attempted to add bureaucratic heft to U.S. development assistance programs by creating a new position, the director of foreign assistance (who also headed USAID), within the State Department. This new position was one of many Rice reforms aimed at reconfiguring the State Department to conduct “transformational diplomacy.”

Although admirably seeking to address inadequacies in the status quo, these reforms tied democracy assistance more closely to other U.S. foreign policy goals. Problems inevitably arise when U.S. short-term security interests clash with the longer-term goals of promoting development and democracy. Another challenge occurs when democratic activists working in countries that have strained relations with the United States do not want to receive assistance directly from the State Department, for fear of being labeled traitors. Greater levels of democracy assistance funding were concentrated within the State Department and other parts of the U.S. government at a moment in history when much of the world had grown suspicious of American intentions. As Thomas Carothers wrote at the end of the Bush Administration, “People the world over see democracy promotion as a dishonest, dangerous cover for the projection of U.S. power and influence.”

The Obama Administration experimented with changes in the delivery of economic and political assistance, including the Quadrennial Diplomacy and Development Review, which aimed to replicate the planning exercise in policy and implementation conducted by the Department of Defense. New emphasis on international cooperation helped to launch the Open Government Partnership, a voluntary multi-stakeholder initiative designed to elicit government pledges for increased transparency. Additional changes included a policy office at USAID, greater emphasis on evaluation, and the Power Africa initiative.

President Trump focused little on promoting democracy or development and instead tried to cut spending on these programs, an aim that Congress thwarted. His administration signaled an intent to merge USAID into the State Department; that effort, fortunately, failed. In March 2018, Secretary Mike Pompeo spoke of restoring American diplomacy and projecting a U.S. presence into “every corner, every stretch of the world”—yet budget proposals called for steep cuts to USAID and the State Department that undercut both foreign aid and our diplomatic clout. The State Department’s budget requests have risen only incrementally—$39.3 billion for 2019 (including $16.8 billion managed by USAID), $40 billion for 2020 (including $19.2 billion for USAID), and $41 billion for 2021 (including $19.6 billion for USAID).

Over a decade ago, Chairman of the House Committee on Foreign Affairs Howard Berman declared,

It is painfully obvious to Congress, the administration, foreign aid experts, and NGOs alike that our foreign assistance program is fragmented and broken and in critical need of overhaul. I strongly believe that America’s foreign assistance program is not in need of some minor changes, but, rather, it needs to be reinvented and retooled in order to respond to the significant challenges our country and the world faces in the 21st century.

Little has changed since then. It is time to rethink some of our theories about the relationship between development and democracy promotion, then reorganize to achieve these objectives more effectively.

Development and Democracy

To compete with China and Russia in the 21st century, U.S. decision-makers must start by interrogating the modernization theory at the center of U.S. development assistance over the past half century. Since the creation of USAID, many aid projects have assumed, explicitly or implicitly, that economic development had to come first, with the hope that it would eventually produce demand for democratic change. Thus, development agencies provided resources that stimulated growth, reduced poverty, and supported economic development irrespective of regime type. Aid projects that strengthened autocrats could be excused as promoting democracy over the long haul. (During the Cold War, this formulation also provided cover for assisting autocratic regimes aligned against the Soviet Union.) Elaborate theories were even constructed to explain the evolutionary potential of autocratic regimes—i.e., those aligned with the United States—versus totalitarian regimes—i.e., those aligned with the Soviet Union.

In the 1990s, after the Cold War ended, this assumption about the sequence of development and democracy led U.S. decision-makers to focus the lion’s share of U.S. assistance to Russia on economic reform, propelled aid to African strongmen voicing commitment to economic reform, and provided the rationale for an emphasis by the World Bank and other donors on economic projects rather than political reforms in the People’s Republic of China. In the early 1990s, at the peak of American power and the ideational hegemony of liberalism, it seemed to many that all development paths would eventually lead to democracy.

The package of neoliberal economic reforms promoted in the 1990s as the Washington Consensus did produce economic growth. Sometimes the economic modernization supported by the United States did produce democratization. Future modernization—as well as urbanization, education, and the rise of a propertied middle class—might eventually create pressures for democratic change in places like China and Russia. Over the long stretch of history, the correlation between the world’s richest countries and democracies is still robust.

Today, however, we can longer be certain. New surveillance technologies may give contemporary autocracies a longer shelf life. The Chinese model of economic development may prove to be a lasting alternative to the Western model. Russia’s transition from communism to capitalism in the 1990s has empowered, not weakened, Putin’s personalistic dictatorship. In Africa, Central Asia, the Middle East, and Southeast Asia, some American economic assistance programs have strengthened autocratic and semi-autocratic regimes rather than prodded political liberalization.

In our new era of great power ideological competition, there remains little justification for separating the promotion of development and democracy in assistance programs. In the 1990s, that strategy helped to produce the threats we now face, especially from China but even from Russia. We should stop repeating these mistakes—and remember that a similar theory during the Cold War allied the United States unnecessarily with many repressive regimes.

Strong scientific evidence now shows a positive relationship between development and democracy. Indeed, the causal arrow may even be reversed: Democratic breakthroughs in developing countries can spur economic growth, democracies can facilitate economic development just as well as autocracies, and new democracies do not show declines in development. Therefore, the artificial distinctions between development, democracy, governance, and the rule of law should end when it comes to strategic thinking, government organization, and resources.

Environmental sustainability must also be integrated consciously into development and governance aid programs. We should seek sustainable development, not promote short-term economic growth that does long-term damage to the planet.

If China is exporting a model of autocratic development, then the United States must promote a model of democratic development. If Beijing pushes a state-led model, Washington must promote a market-led model. Moreover, in our new ideological age of competition between autocracies and democracies—illiberalism and liberalism—U.S. assistance should focus on aiding countries and societies openly aligned with our liberal democratic values; there should be no more aid to strongmen in the hope that they will eventually democratize.

Our current approach and structure for the provision of foreign assistance cannot accommodate this new approach and has little chance of enabling us to compete successfully with China in the decades to come. We currently spend less than 0.25 percent of GDP on foreign aid. In FY 2020, the USAID budget totaled $19.2 billion, compared to $718 billion for the Department of Defense; the new, bipartisan National Defense Authorization Act likely soon to be passed is $740 billion. The prestige gap between defense and development work is even deeper than these budget asymmetries. The secretary of defense is a member of the cabinet who oversees the largest civilian workforce in the U.S. government, in addition to 1.3 million active duty and 800,000 reservist service members under the secretary’s command. In contrast, the head of USAID holds the inglorious title of “administrator,” is not a member of the cabinet, and supervises around 4,000 employees. Moreover, USAID does not own the mission of development: Over two dozen agencies and organizations do development work, including the Pentagon itself. To compete with China over the next century, our organization and philosophy about democracy and development promotion have to be transformed.

Most ambitiously, President Biden and Congress could create a new Department of Democracy and Development, or a Department of Sustainable Development (DSD). The United States can no longer support “international development” for its own sake but must explicitly add normative commitments to democracy and sustainability to the mission. The current USAID would constitute the core of this new department; but parts of the Departments of Defense, Treasury, Justice, Agriculture, and Commerce that are currently engaged in promoting democracy, development, and the rule of law would be integrated into it. From the Department of State, the Bureau of Conflict and Stabilization Operations, the Office of Foreign Assistance, and MEPI should be merged into this new department. If not reconstituted as an independent agency, the Open Technology Fund currently housed at the U.S. Agency for Global Media also could be incorporated. The MCC and the U.S. International Development Finance Corporation should maintain their autonomy but be folded into this new department as well.

These restructuring moves are just a partial list; every part of the U.S. government dedicated to providing aid for development and democracy must be brought in. The only exception is military assistance, which should remain at the Pentagon. The State Department should maintain control over some economic bilateral assistance, but this funding must be used for achieving diplomatic, not development, outcomes. The days of pretending that there are no differences are over (Google “aid to Egypt” for the last several decades to see how we have pretended in the past).

The future head of this department would be a cabinet member. Rather than reporting to the secretary of state, the new department would be autonomous and could therefore focus on long-term strategic goals of development and democracy support rather than being guided by short-term diplomatic or security interests. (The State Department’s Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor would focus its work on policy and diplomacy in support of democracy, but no longer directly fund foreign NGOs.)

Research shows that economic assistance tied to short-term geopolitical goals has rarely produced sustained positive development outcomes. Direct assistance through the new department, therefore, must be firmly conditionedon pursuit of long-term development and democracy objectives, not short-term national security interests. Conditionality metrics used by the MCC could serve as a baseline model for all American assistance except emergency humanitarian aid. If the United States has a national security interest in providing an autocratic regime with military aid or antiterrorist assistance, this aid must not be called democracy assistance or development aid and should be provided by other government departments.

A new department, separate from and equal to both the State Department and the Defense Department, will have greater capacity to promote economic development, democracy, and the rule of law as long-term, sustainable goals not influenced by immediate U.S. diplomatic issues.

Moreover, the new department would discontinue the policy of compelling aid recipients to buy American products, a practice that has not produced positive economic development outcomes. The Department of Commerce or Department of Defense could continue this practice, but it should be clarified that such aid is provided explicitly for American commercial or security purposes, not development or governance goals.

The creation of the new DSD also would produce the conditions for nurturing greater expertise and clearer separation of missions from those of either the Department of Defense or the Department of State. Diplomats lack the training to construct effective democracy, governance, and rule of law programs. Likewise, diplomats serving in embassies abroad should not engage an autocratic government on mutual security issues in the morning, and then hand out democracy grants to opposition leaders in the afternoon. The Department of Defense should return to its core missions and get out of the business of rule-of-law promotion and other democratic assistance programs.

Along the lines suggested, to the greatest extent possible this new U.S. government department should stop providing direct grants and resources to foreign NGOs. Such transfers are hard to explain and justify to foreign governments and always carry the taint of U.S. government meddling in the sovereign affairs of other nations—especially in democracies, since dictators have a much weaker claim to be representing the sovereign interests of their citizens.

Instead, private U.S. NGOs should do that work. One strategy to increase support for non-governmental democratic organizations would be to expand vastly the National Endowment for Democracy (NED), a process that ironically began during the Trump era due to congressional insistence. To do so, NED would have to be prepared to give more grants to American NGOs and foundations currently funded by USAID that provide technical assistance and direct financial support to foreign partners beyond NED’s traditional core subgrantees, NDI, IRI, CIPE, and the Solidarity Center. As an example, NED could back American NGOs that support independent media and anti-corruption efforts, and that work directly with local partners all of the world.

A second strategy for providing more effective and sustainable support for civil society globally in a way that is more independent from the U.S. government would be to establish more regional and functional foundations. For instance, MEPI, currently located within the State Department’s Bureau of Near Eastern Affairs, could be privatized as a new Middle East Foundation modeled after the Asia Foundation or Eurasia Foundation. These regional foundations, as well as new ones in Africa and Latin America, could then inherit from USAID greater responsibility for funding and assisting civil society organizations locally, but with more distance from U.S. embassies and short-term U.S. foreign policy objectives. More functional foundations also could be stood up, for instance, to support women’s rights, sustainable development and governance, independent media, transparency, or fighting corruption. More sources of funding for NGOs—both American and foreign—also create better conditions for competition within the sector.

If new, more independent foundations cannot be established, USAID must at least stop writing contracts for “implementors” to do democracy assistance work, and instead award only grants. Even the word “implementor” should be retired, since it suggests that recipients of these funds have no autonomy but are only implementing U.S. government policy. The more separation between the U.S. government and American democracy-promoting NGOs, the better.

Greater rigorous, independent, evidence-based evaluation must accompany all of these organization changes. After fourteen years of democratic backsliding, U.S. democracy promoters and human rights defenders must be challenged to rethink their strategies and assumptions. Independent evaluation will help this process.

The creation of a new DSD, together with an expanded NED and/or parallel independent foundations to support NGOs, would enable the United States to compete more effectively against China’s developmental assistance efforts. By establishing a normative commitment to liberal economic and political institutions—not just generic poverty reduction or development—these approaches offer a clear alternative to the Chinese model.

Global demand for such an alternative is still robust. Especially after Biden’s electoral victory, democracy advocates throughout the world are looking to the United States for solidarity, support, and guidance in strengthening their democratic institutions, governance models, and economic competitiveness. Letting them down would not only contribute to democratic backsliding throughout the world, but would also strengthen Chinese and Russian efforts to advance their illiberal ideologies. A new effort to support democratic values abroad, intertwined with assistance for economic development, is not only the right thing to do, but the prudent approach for advancing American security goals.

Democrats of the World, Unite!

President-elect Biden already has committed to convening a Summit for Democracy, a terrific occasion for enhancing coordination and solidarity among both democratic governments and democratic activists around the world in support of liberal values. Given the erosion of democracy within the United States and limited American success in promoting democracy lately, Biden is absolutely correct in seeking to join with other democratic forces in the world and make the promotion of these universal values a collective effort. As Thomas Carothers and Frances Brown have written, “Innovation with newer, non-Western democracies makes the case for treating democracy building as a mutual learning exercise rather than an export business.” The illiberal, anti-democratic forces in the world are connected. Liberal, pro-democratic forces should unite as well.

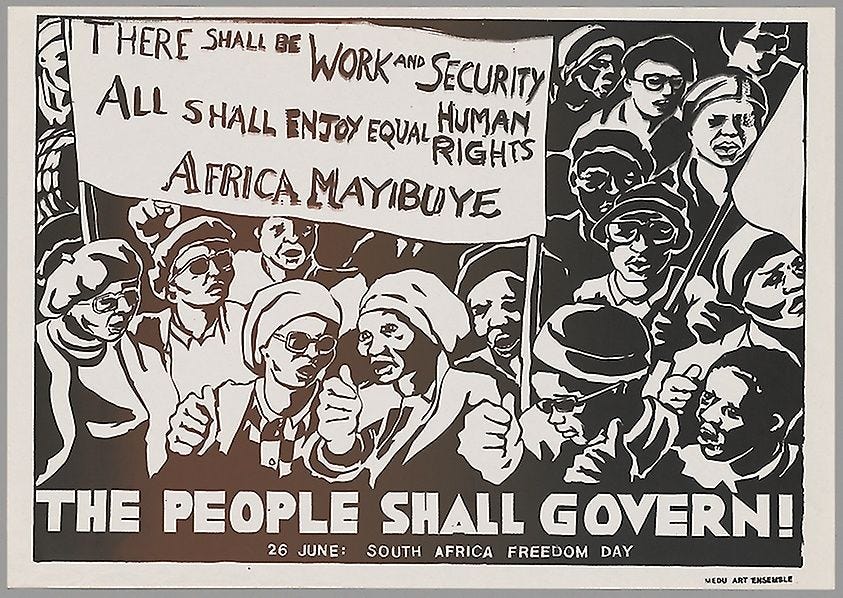

A summit with nothing left behind, however, will be a missed opportunity. This event must commit to new principles that do more than just reaffirm liberal democratic values. A new doctrine on social media regulation, research and development cooperation among democracies, the right to assist democrats working in non-democracies, and a commitment to integrate democratic and rule-of-law norms as well as green polices into traditional economic development programs are just some elements that are needed and should be codified as norms in a written document—perhaps titled the Freedom Charter, Democracy Charter, or Liberty Charter.

Second, the summit should establish structures to sustain and strengthen connectivity among democracies, be they D-10 (the current G-7 members, plus South Korea, India, and Australia), D-20, T-12 (twelve techno-democracies), or a scaling of Digital Nations. The existing Community of Democracies could be restructured and reinvigorated as the secretariat for this new multilateral democratic organization (but if this idea is pursued, then some current members of the Community of Democracies with dubious democratic credentials would have to be suspended.)

Third, the summit should create one or more new multilateral organizations to support global democracy. We have a World Bank; why not a Global Foundation for Democracy? A new Global Foundation for Democracy could not only provide direct assistance to civil society organizations, but could also could facilitate training programs, provide legal assistance for independent journalists and human rights activists, offer secure data cloud storage for partners around the world, and create a digital market matching donors and civil society groups—an eBay or Craigslist for democracy, or a Civil Society Marketplace. (For details, click here.) The latter could help to democratize and expand donor support for democratic organizations around the world. A rancher in Montana—not just major foundations—could become a verified donor and transfer support directly to a verified recipient of a women’s rights organization in Pakistan.

Scaling, sharing, and internationalizing the infrastructure for democratic activists around the world could have the same disruptive effect on this “donor-recipient “market” as other recent tech companies have produced on commercial markets. This new organization could be structured to allow for not only government-to-government partnerships, but also private-public funding and programs. Less ambitiously, the summit could create a new international foundation in support of independent media, or a new foundation to support transparency and fight corruption. A compelling feasibility study has already been conducted for the creation of an International Fund for Public Interest Media.

The summit could at least establish some norms for better coordinating bilateral and EU programs of democracy support. And of course, the summit should include activists, civil society leaders, academics, and journalists committed to democracy around the world. The World Movement for Democracy could help to bring these non-governmental voices to the gathering. The organizers should establish strict criteria for invitation—no pseudo-democracies or government-organized NGOs. Including a strong analytic component in the proceedings—academics who can diagnosis the causes of democracy’s decline as a first step towards devising policy solutions—would enhance the chances of a successful summit.

In addition to a Summit for Democracy with deliverables, the Biden Administration must rejoin and reengage with existing multilateral organizations and standard-setting bodies to support liberal democratic norms within these bodies, be it the UN Human Rights Council, the World Trade Organization, the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe, or even the Association of Southeast Asian Nations—a body in which not all members are democracies. The Trump Administration ceded many of these spaces to Chinese diplomats. We have to get back in the game. A bold start would be to reinvigorate the Democracy Caucus in the United Nations during the UN General Assembly next September. President Biden also should explore ways to formalize deeper normative commitments to defending democracy within the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue, or “the Quad”—the United States, Australia, India, and Japan—and even start discussions to join the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for the Trans-Pacific Partnership, with an even greater focus on democratic norms, fair trade, and commitment to sustainability.

Finally, the global mission of assisting democracy cannot be limited to one summit or confined to governments. “Small d” democrats or “small l” liberals in the United States—not just the U.S. government—must unite with ideological allies around the world to seek new ways to renew universal commitment to these values. This long-term project is both normative and educational; it must involve not only activists but academics and public intellectuals. It must also be intertwined with a defense and promotion of economic liberalism.

In an interview with the Financial Times last year, Putin declared that liberalization has become “obsolete.” Likewise, President Xi has championed his regime’s model of development and governance as superior to allegedly antiquated market and democratic systems. We have heard these predictions before, in the 1930s during the Great Depression and the rise of fascism, and again in late 1940s, when we “lost” Eastern Europe and China and the Soviet Union looked ascendant. We endured another, deeper round of pessimism in the late 1960s and early 1970s, when democracy in America did not seem to be working well and communism appeared to be on the march in Southeast Asia, southern Africa, and Latin America.

In retrospect, we know that these predictions of democracy’s demise were wrong; liberalism did not die. We have renewed democracy at home and abroad before. With hard work and clarity of vision, we can do it again.

Michael McFaul, a member of the editorial board of American Purpose, is director of the Freeman Spogli Institute for International Studies, Ken Olivier and Angela Nomellini Professor of International Studies, and Peter and Helen Bing Senior Fellow at the Hoover Institution, all at Stanford University. He served as senior director for Russian and Eurasian Affairs at the National Security Council and as U.S. ambassador to the Russian Federation in the Obama Administration. This article is the second in a series of three adapted from his forthcoming book, American Renewal: Lessons from the Cold War for Competing with China and Russia Today (2021).