Sources of the Self

Two summer reads shed light on expansive approaches to freedom in a liberal society. Francis Fukuyama’s latest.

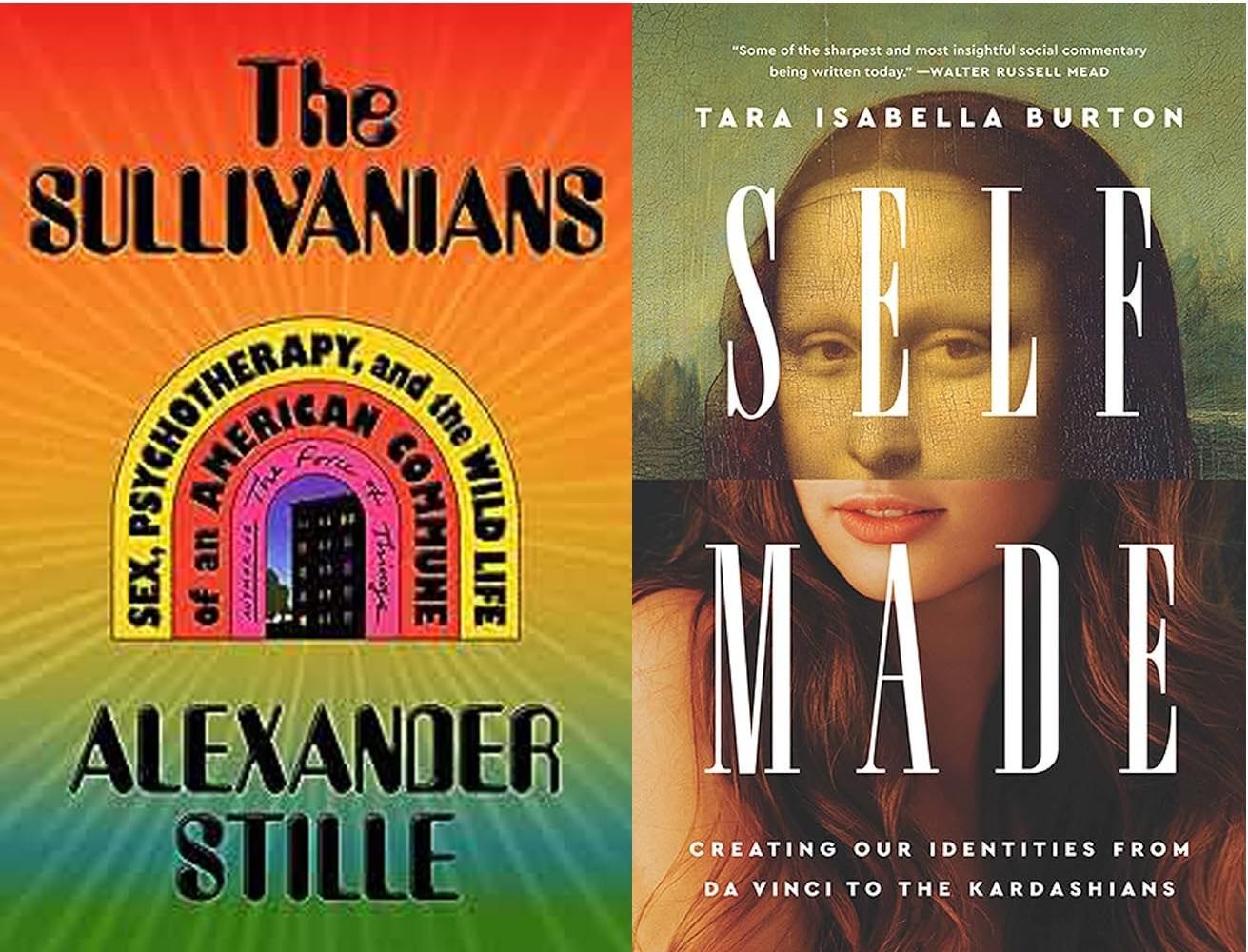

This summer I read two books that give great insight into how the modern idea of the self has evolved, and the bizarre places that journey has led to. The first is Self-Made: Creating Our Identities from Da Vinci to the Kardashians by Tara Isabella Burton, who has written previously for American Purpose; and the second is The Sullivanians: Sex, Psychotherapy, and the Wild Life of an American Commune by journalist and author Alexander Stille (who has previously written on how Silvio Berlusconi destroyed modern Italy).

Burton’s book begins with philosopher Charles Taylor’s observation in his 1989 book Sources of the Self that the Western world has moved from a God-created and God-centered world to one centered on the self. The font of all value was no longer externally determined by a divine order, but lay inside each one of us. And what lay inside ourselves at the deepest level was not a moral being à la Kant, but simply our desires. In this process we came to worship not God but ourselves, or perhaps as some would have it the god that lies within each of us.

Tara Isabella Burton on Self Creation across the Ages

Hear Richard Aldous' podcast with Tara Burton

___STEADY_PAYWALL___Self-Made takes us through a series of individuals who, over the centuries since the Renaissance, have made self-creation their life’s work. This begins improbably enough with the German painter Albrecht Dürer, who in addition to being a great painter and print-maker had “an extraordinary knack for self-promotion,” and portrayed himself not just as an aristocrat but as a god. It was during and after the Enlightenment, however, that the external order was explicitly replaced by something inside of us, the inner self. Jean-Jacques Rousseau was critical to this transition; he argued that “natural man,” unencumbered by the layers of social convention imposed by modern life, was genuinely happy because he could feel the sentiment of his own existence. Feeling and emotion began to displace reason and moral choice as the source of value.

It is not an accident, in Burton’s telling, that those individuals who cultivated those inner feelings most exquisitely were offbeat characters like Diderot’s fictional nephew in the dialogue of that name, or the Marquis de Sade, who elevated sexual perversion to an art form, or the English dandy Beau Brummell. Brummell created a self around clothing and a haughty attitude toward even the highest-status aristocrats around him, because he persuaded others that true value lay in the expression of a creative inner self that only he possessed. As we get closer to the present, the highest forms of self-creation get linked to transgression, and particularly sexual transgression, practiced by figures from Oscar Wilde to Jackie Curtis and her mentor Andy Warhol to Paris Hilton and Kim Kardashian. Even mainstream Christianity gets converted from the worship of God to the worship of the “god within ourselves,” where devotion becomes self-cultivation and self-enrichment.

Where this liberation of the inner self ultimately leads is brilliantly illustrated in Alexander Stille’s The Sullivanians. The Sullivan Institute was founded by and named after Harry Stack Sullivan, a pioneer in the American neo-Freudian school of psychiatry, and by a sometime couple, Saul Newton and Jane Pearce, in New York during the 1950s.

Freud himself had an ambivalent view of the self and society. In Civilization and Its Discontents, he noted how repression of the ego led to neuroses and mental illness, but he also believed that civilization could not exist if everyone simply played out their fantasies. The American neo-Freudian school, by contrast, firmly took the side of the self. Newton and Pearce co-authored a book entitled The Conditions for Human Growth, which became a manifesto for the movement they founded. They started with Freud’s premise that human beings were born with powerful drives toward aggression and sex, but unlike Freud argued that human autonomy was illegitimately repressed by society. In Stille’s words,

Pearce and Newton offered a more exciting and hedonic variation on traditional psychoanalysis. Their goal was to be the champion of all the repressed desires that had been . . . shunted aside during childhood. As they put it, ‘The child learns to repress all of its deepest desires and needs in order to avoid displeasing his or her parents.’

The Conditions for Human Growth argued that the nuclear family was in essence the source of all evil, a repressive force that stood in the way of genuine self-expression. The institute they founded advised its “patients” to break completely from their parents, but also to give their children up to communal upbringing and to deny them contact as they matured. Consistent with this view, they attacked the idea of monogamous relationships, and in the group houses they created encouraged everyone to have sex with as many partners as they could. The Sullivan Institute turned into a cult in the heart of New York City that attracted a large number of artists and writers in the 1960s and 70s, including the painter Jackson Pollock, the writer Richard Price, the art critic Clement Greenberg, and the singer Judy Collins.

It is perhaps not surprising that the agenda of personal liberation was linked to a revolutionary political agenda that dovetailed with the radical politics of the 1960s. Pearce and Newton believed that communism in the Soviet Union had failed because it left the nuclear family intact. Only by liberating children from their parents could the possibilities for “infinite growth” be realized. For them, the nuclear family was the mechanism by which capitalism reproduced itself.

The leadership of the Sullivan Institute came to replicate many of the pathologies of the communist system it admired. The top leaders became increasingly autocratic, controlling, and paranoid, and began to use violence to enforce their dictates. Saul Newton and his fifth wife, the soap opera actress Joan Harvey, ordered their patients to have sex with them, took children away from their parents while directing the latter to have sex with multiple partners, and arbitrarily dictated the most intimate details of the lives of the members of the commune.

Today, Newton’s sexual predation (including with underage girls, a practice that he continued into his 80s) would be criminally prosecuted. The organization finally fell apart by 1991 as members began suing the institute for the right to have custody over their own children, and the discovery of gross financial irregularities on the part of its leadership. While some members remained trapped within the cult’s orbit to the end, there were many tragic stories of children being kept from their parents throughout their childhoods, of grown children refusing to visit their dying parents, and families losing touch with close members for decades at a time.

Tara Burton is restrained throughout Self-Made in passing moral judgments about the growth of self-worship and the narcissistic, self-indulgent characters that this movement has produced. She nonetheless makes clear in her epilogue that “self-making” is a very problematic phenomenon that has the effect of devaluing social obligation—the sorts of constraints and rules that make societies possible.

The Sullivan Institute was a perfect instantiation of many of the pathologies she describes. The inner self was understood simply as desire—indeed, at its core sexual desire. Personal development (or what Newton and Pearce referred to as “infinite growth”) did encourage artistic expression and their institute did include many artists in its circle. But for many, personal liberation was nothing more than the maximization of sexual opportunity. Human autonomy had nothing to do with moral autonomy or the ability to exercise self-mastery as earlier philosophical traditions would have maintained. Rather, autonomy implied the relaxation of all inner constraints in the pursuit of pleasure. The Institute’s doctrine attacked the natural feelings of love and affection that parents and children have for one another as destructive instincts that harm the inner growth of both parties.

One of the charges made against modern liberalism is that liberalism’s protection of a sphere of personal autonomy tends to expand over time to encompass all sorts of asocial and self-destructive behavior. Individuals come to understand freedom not just as freedom to act within an existing moral tradition, but rather to make up new traditions and rules. The freest person in the world is Nietzsche’s character Zarathustra, who transvalues all existing moral systems into one of his own creation. This is what the Sullivanians attempted to do, upending not just the conventional bourgeois morality of 1950s America, but the natural instincts of love and affection on which bourgeois morality was based. That project ended in failure and wrecked lives, and the Sullivan Institute eventually collapsed of its own self-contradictions. But the instinct to expand the sphere of individual autonomy in disregard of both convention and human nature remains a powerful one today.