Barring a seismic shift in public opinion over the next six months, the Republican Party will become the majority party in the House of Representatives. And unless there is some unforeseen upheaval in the House Republican caucus, current Minority Leader Kevin McCarthy, the eight-term member of Congress from California, will likely become the Speaker of the House. He will not only be the presiding officer of that body, as provided for by the Constitution, but by statute, he’ll also be second-in-line to succeed the President should he or she die, resign, or be forced from office. In other words, it’s a big deal who the Speaker is—or, at least, it should be.

As such, past and more recent revelations about McCarthy’s behavior in the aftermath of January 6 are bound to give one pause. That very night, the Minority Leader spoke rather elegantly about the day’s events, calling them “unacceptable” and saying “we all should stand united in condemning the mob together,” but later deep-sixed sanctioning his party’s participation in the select committee designed to look into the events of that day. During the attack on the Capitol, McCarthy correctly had called Trump, telling him the rioters were his supporters and that it was his responsibility to call them off. When the President brushed McCarthy’s pleas aside, McCarthy apparently yelled, “Who the f…k do you think you are talking to?”

Yet before the month was out, McCarthy was down in Mar-a-Lago, smoothing things over with the former President. What wasn’t known then was that, in the immediate aftermath of January 6, McCarthy told House colleagues in private that he would urge Trump to resign and that he had “had it” with him. When the New York Times reported what McCarthy had said this April, he denied ever saying such—a denial quickly shown to be a lie when the Times reporters produced audiotapes of the conversations. What soon followed, much like in January 2021, was McCarthy calling Trump to smooth things over once again. He was obviously concerned that an angry Trump might spoil his goal of becoming Speaker by turning a significant number of the GOP House membership against him.

To be sure, becoming Speaker is something of a popularity contest. A majority within a party picks their candidate for Speaker, and, in turn, the majority party then elects its candidate, Speaker. But it’s worth noting that, strictly speaking, the Constitution does not require the Speaker to be an elected representative—suggesting, to one degree or another, that the presiding officer of the House was meant to have institutional responsibilities beyond the day-to-day politicking that occupy an individual representative. And while Speakers, both in England and the North American colonies, were clearly selected with an eye to partisan leanings, they were nevertheless expected to uphold the dignity of the legislature and ensure its sound running as a representative body. To do so, the Speaker (optimally) would be firm but fair in his rulings and, in key moments, capable of seeing the interests of the institution over and above the politics of the moment.

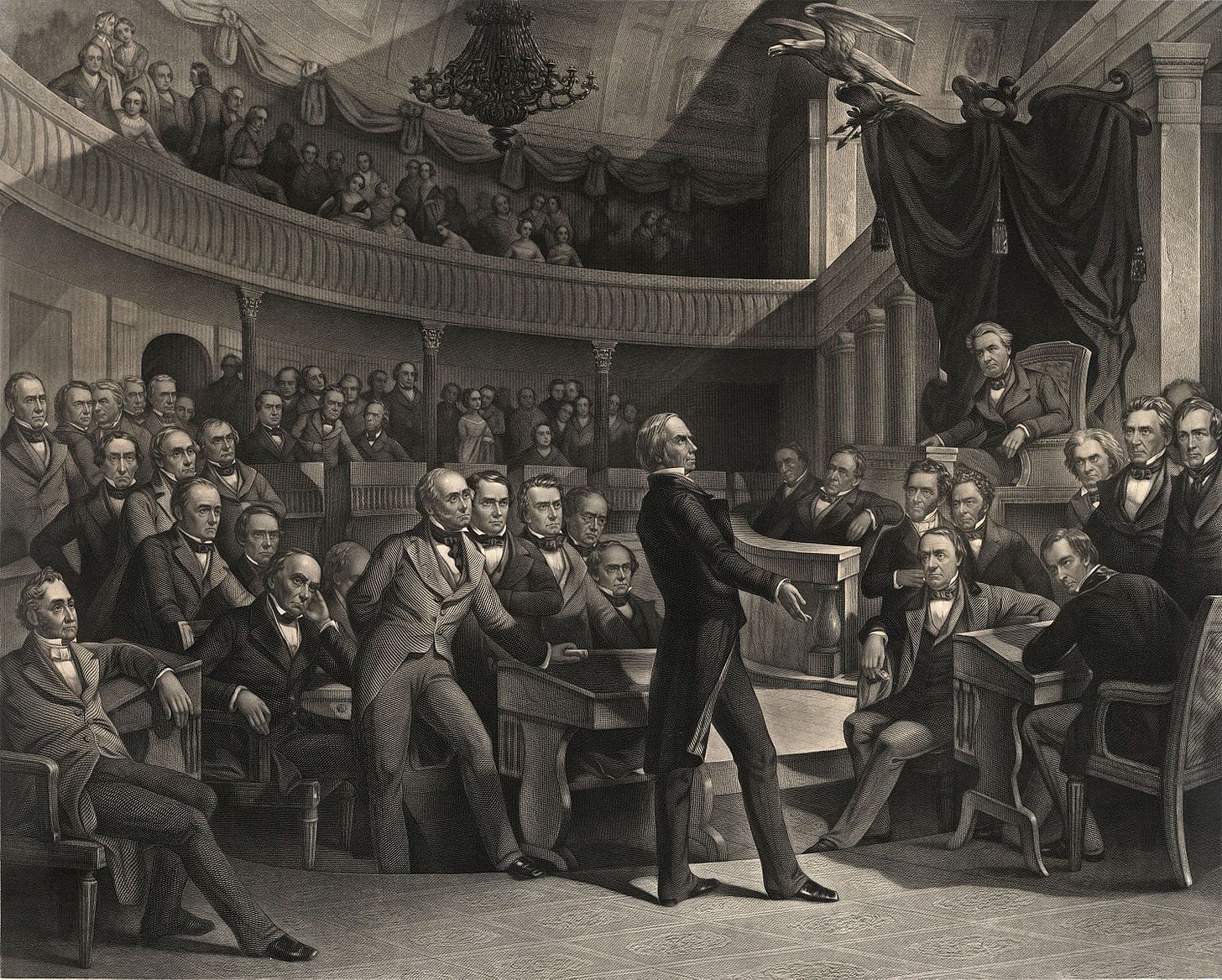

Reconciling these two poles in practice is admittedly not the easiest of tasks. However, it’s perhaps the most important reason Henry Clay ought to be considered the greatest of the U.S. Speakers. Clay was first elected to the House from Kentucky in 1810 and was immediately picked as Speaker. He would go on to be selected as Speaker six different times. A powerful orator, with a coherent policy program (the “American System”) that appealed to political factions in the Northeast and the West, Clay was popular and influential. Indeed, much of his agenda initially was at odds with the policy preferences of James Madison, his party’s occupant in the White House. But for all of Clay’s popularity and factional influence, he was also responsible for expanding and more firmly establishing the House’s system of standing committees. Clay may have had multiple motives for doing so, but the end result was an institution with an expanded capacity to carry out its legislative functions and that more clearly reflected the country’s growing diversity of interests and policy concerns.

Speakers since Clay have come and gone, some notable like “Uncle” Joe Cannon (1903–11) and Sam Rayburn (1940–47, 1949–53, 1955–61), others far less so. Some have been strong; some weak. Some operating under a strong party system; some dealing with strong committee chairs. Given the paucity of guidance from the Founders or the text of the Constitution about the office, its history is unsurprisingly often seen as a product of the political times and the particular personalities of the Speakers.

Today’s iteration of the office is a product of weak parties, ideological polarization, and Newt Gingrich’s “revolution.” Upon becoming Speaker in January 1995 after the Republicans gained control of the House for the first time in forty years, Gingrich set out to remake how the House would operate. The Speaker would name committee chairs, with seniority on a committee no longer being determinative. Once named, a chair would be subject to term limits. At the same time, Gingrich expanded his leadership and communications staff while cutting standing committee staff by a third and giving the Republican Policy Committee greater sway. The reforms were intended to move power from the committees to the Speaker when it came to actual legislative proposals and messaging. Gingrich’s goal was to be the political generalissimo, leading a unified party into battle with the opposition, armed with the national agenda he and his leadership team had crafted.

Building on the growing ideological coherence within the two parties—with Republicans conservative and Democrats liberal—Gingrich was putting the speakership on institutional steroids. With the legislative controls in hand, the Speaker would strive to heighten the contrast between Republicans and Democrats. House members would increasingly take their cues from the Speaker’s office and focus less on their more traditional task of representing the particular interests and wants of the folks back home. As a result, proposed bills and voting often became as much about how they might play in the next election as the substance of the legislation itself. It was a bit of the dog chasing its own tail. To keep party lines clear in the hope of maintaining its majority, Gingrich and the Speakers who have followed are disinclined to muddy up the legislative process that inevitably comes with building a consensus for a measure that reaches across party lines.

Arguably, after his “reforms” had been put in place, Gingrich had as much institutional control as any Speaker since Cannon. But what Gingrich didn’t have was control over the Senate—which operated by a different set of rules—or over the President, whose veto authority leverage let him block legislation with only a third of either house. Moreover, while Cannon operated when party discipline was the norm and party bosses decided who ran for office and who didn’t, Gingrich had to deal with members whose campaign monies were largely independent of the party and who were nominated in open primaries that the party had virtually no say over. Dennis Hastert, the then Deputy Whip, quoted Gingrich as telling his leadership team, “Well, from now on, the six of us are going to make all the decisions.” And they did. But, as Gingrich discovered relatively soon, making decisions is one thing, getting something done is another.

But rather than rethinking their creation, neither Gingrich nor his successors have reversed course and, as my AEI colleague Philip Wallach writes in his forthcoming book, Why Congress, they have “never considered how a less partisan, less top down, more deliberative approach might have strengthened Congress’s hand in negotiating with the president”—or, for that matter, with the Senate. Such an approach might be more time consuming and require a sense of comity that can be difficult to come by. Nevertheless, its results may be more durable precisely because they are more reflective, as Wallach argues, of the country’s actual and intended diversity.

Today, the Speaker’s “paper” authority is less impressive than it seems. Without real party discipline, ambitious House members are more likely to invest their time and resources into how to grandstand politically than to build up a reputation for, say, committee work or legislative accomplishments. The institutional reforms Gingrich put in place incentivizes such behavior. As a result, the caucus that is the ground on which the Speaker holds and operates his office is soft, shifting, and bedeviled by ideologically fractious members. All one must do is look at the frustrations of Speakers John Boehner and Paul Ryan—two politicians of quite different stripes—to recognize that the problem goes deeper than the person holding that office at any given moment.

Although Kevin McCarthy is no Newt Gingrich, his speakership, if it does come to pass, might well be the logical result of the changes made to the office by Gingrich. His actions as Minority Leader are consonant with what Speakers are required to do today both to be elected and to hold on to the office once elected. To keep any semblance of coherence within the party, placating rather than leading is now the norm. It would be pollyannish to think a Speaker could be blind to the politics of the office. Nevertheless, when the office is hardly anything but partisan, what is lost is the Speaker’s responsibility to see that the institution itself is in good working order as a representative and deliberative body.

Gary J. Schmitt, a contributing editor of American Purpose, is a senior fellow in social, cultural, and constitutional studies at the American Enterprise Institute.