Stargazers of Beauty

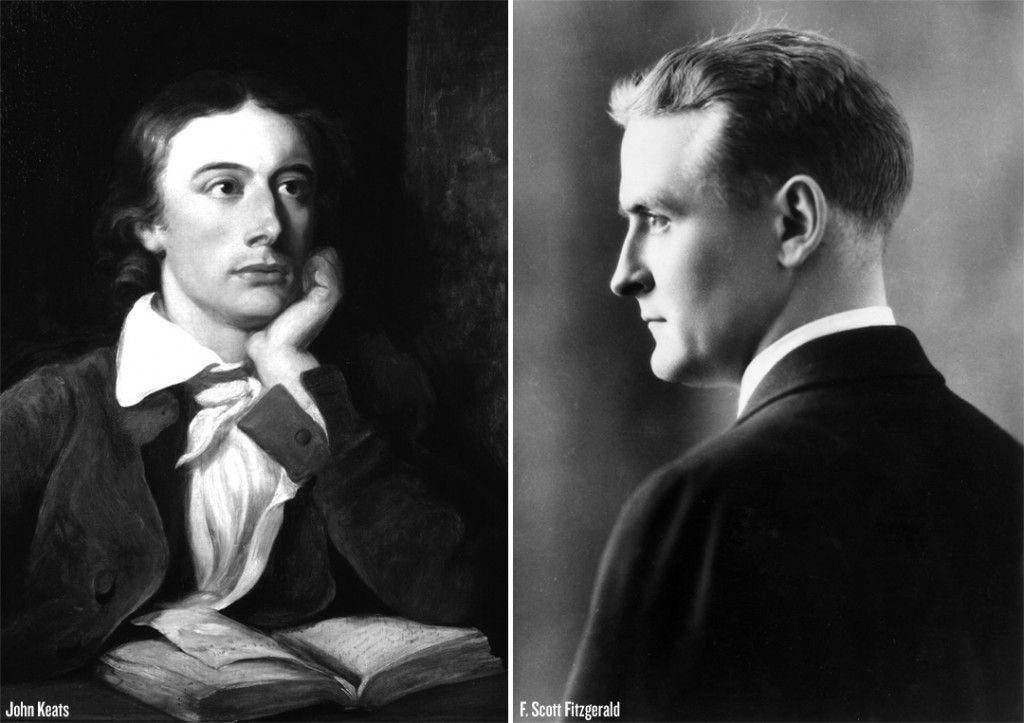

Jonathan Bate's book "Bright Star, Green Light" finds striking parallels in the life and work of John Keats and F. Scott Fitzgerald.

Bright Star, Green Light: The Beautiful Works and Damned Lives of John Keats and F. Scott Fitzgerald

by Jonathan Bate (Yale University Press, 432 pp., $15.78)

Oscar Wilde once quipped that the two greatest tragedies in life were not getting what one wants, and the other is getting it. F. Scott Fitzgerald admired Wilde, recommended his plays, and shared in his idolizing of the brilliant, doomed poet John Keats. In Bright Star, Green Light Oxford scholar Jonathan Bate appreciatively explores the similarities in the life and work of Fitzgerald and Keats.

It’s easy to link the two thematically and biographically, but only to an extent. Though Bate's parallel narratives mostly work, there are some crucial and irresolvable differences between the two men. One glaring example is that Fitzgerald was suddenly served far more than his share of literary fame and fortune very early in life and then desperately watched it all slip away, while Keats died too young to expect anything other than to take his haunting epitaph literally: “Here lies One whose Name was writ in Water.”

Both Fitzgerald and Keats came from humble origins, had lively and distinguished peers, and were possessed by a genius that wasn’t fully recognized until after their deaths. Romantics to the bone, Fitzgerald and Keats were equally motivated by their human muses, Zelda Sayre and Fanny Brawne, as by their longing for Beauty with a capital B: the ideal, the unattainable, that which is so imaginatively close and yet so physically far away. Wilde also said that “we are all in the gutter, but some of us are looking at the stars.” In their own distinct ways, Fitzgerald and Keats were some of our finest stargazers.

Fitzgerald’s passion for Keats, Bate notes, came with a teacher’s careful eye. Beneath his “pose of charm and insouciance,” we should remember that Fitzgerald was a “grafter, a craftsman, who worked and reworked his sentences.” He was fascinated by the way Keats’ line “the hare limp’d trembling in the frozen grass” worked. Bate perceptively appreciates how Fitzgerald’s hushed recitations of Keats and Shakespeare—which, luckily, survive—are moving because he feels every last syllable. Fitzgerald wisely suggested Keats as a never-fail standard for distinguishing “between gold and dross in what one read.”

Bate insightfully compares the twinkling light at the end of Daisy’s dock, the object of Gatsby’s lifelong aspiration, with the “bright star,” distant but glimmering, “in lone splendor hung aloft the night,” addressed in what was probably Keats’ final poem, a sonnet written on a boat on his way to his deathbed in Rome. In contrast, The Great Gatsby (1925) was by no means Fitzgerald’s swan song. He had plenty more good writing left in him, even if his readership decreased. Bate includes an anecdote of Fitzgerald, wanting to perk himself up late in life while grinding it out in Hollywood, going to a bookstore and asking if they had any of his books in stock, only to find that the clerk had never heard of F. Scott Fitzgerald.

The juxtaposition of these two images, Keats’ star probably inspiring Daisy’s green light, illuminates something important. Whether or not your ideal is actually possible, there is nevertheless value in pursuing it anyway. Keats’ line “beauty is truth, truth beauty” resonates because while all things must inevitably pass, true beauty tends to have some staying power. Bates movingly writes that “year by year, the future recedes before us, always elusive, just out of reach of our outstretched arms, like those lovers on the Grecian urn, always in mad pursuit.” Meditating on unattainability, particularly in a culture that constantly urges us to consume and acquire as much as possible, may help keep our wants and needs in perspective.

In this thematic sense, Fitzgerald and Keats are a useful comparison. Yet the more we know about them, the more it’s clear that important parts of their lives and work are quite divergent, which complicates the parallel Bate wants to establish.

Bate’s narrative slightly overemphasizes Fitzgerald’s half of the story. Plenty of high schoolers are assigned Gatsby in English class (at least one hopes they are) and so it’s reasonable to assume that Fitzgerald’s dramatic life story—epic benders, infamous friends, tortured relationships, insomnia in exquisite European hotels—is probably already known by anyone who might pick up Bate’s book. Fitzgerald has the benefit of having lived a life that was at least as interesting as his fiction. In some ways the glittering public image Fitzgerald created for himself slowly faded as the Jazz Age sunk into the Great Depression.

In terms of lifestyle, the two couldn’t be farther apart. Dead at twenty-five, Keats would probably have given anything for another few months in a modest cottage with Fanny Brawne, but he was too busy dying of tuberculosis. Keats, the son of a Cockney stable hand in Georgian London, never came anywhere close to the kind of life Fitzgerald lived, for a time, to the fullest. Fitzgerald, Bate tells us, had plenty of romantic sorrows and died prematurely of a heart attack at forty-four. That said, Fitzgerald did get to enjoy living the high life with his “golden girl,” the vivacious but manic Zelda.

Keats’ premature death is one of literature’s great tragedies because it robs us of so much potential. His best work, according to some, outpaces what other greats had written in their mid-twenties. Keats didn’t even die as Fitzgerald did, as so many artists and poets tend to do, through overindulgence or self-destruction. A surgeon by training, Keats must have caught something contagious while tending to the sick and the next thing he knew he was withering away, coughing up blood, and beginning what he called a “posthumous existence.”

When death-haunted Keats wrote about haunted and mysterious beings, femme fatales, and nightingales and urns, he’s not straining for effect: As much as he believes (or wants to believe) in beauty as truth, he never forgets for a moment that joy’s “hand is ever at his lips bidding adieu.” Keats can write so beautifully about bodies and nature in part because he knew viscerally the raw facts of life that working in a 19th-century surgical ward can teach. Keats was no daydreamer or fantasist; he craved beauty because he was keenly aware of what it was like to be without it.

In contrast, Fitzgerald wrote with plenty of lyricism but crucially matched it with a profound social conscience that wasn’t present in Keats, who certainly hung out with outspoken radicals like Percy Shelley and Charles Lamb and who deeply admired the revolutionary Milton. Had he lived longer, it’s certainly possible that Keats might have developed more of a social critique, but his literary interests tend to be more abstract and elevated than social commentary.

Fitzgerald’s anguished but literarily advantageous position of being on the outside of elite circles looking in gave him a penetrating awareness of the boom and bust cycle of American life. He understood that beauty, often described in terms of the moneyed life of ease, wasn’t all it was cracked up to be. It’s not accidental that his stories often concern ambitious, prominent men and women in various stages of moral and economic decline and that Gatsby’s fate is sealed by a sudden car crash.

Bate doesn’t emphasize this as much as he might have, but both writers have something unique to offer to us today. Keats’ emphasis on the imagination, and the worlds he conjures in an impressively small number of words, open up a quiet space for our own imaginations, constantly ruptured by technology’s endless interruptions and distractions, to grow. Despite his flamboyance, Fitzgerald was no fool about the steep precipice waiting at the end of all those “vast filling stations filled with money.” Roughly a century ago, Fitzgerald diagnosed the self-obsession and materialism of our time by looking squarely at his own. At his best Fitzgerald diagnoses the diabetes of the soul that results when getting what we want is not enough, while Keats reminds us, especially after a pandemic, that we should be grateful to have anything at all. Bate’s tidy set of parallels collides with the untidy reality of two rich and complex lives and bodies of work.

Matt Hanson is a contributing editor of American Purpose and The Arts Fuse, Boston’s online independent arts and culture magazine. His work has appeared in The Baffler, The Guardian, The Millions, The New Yorker, The Smart Set, and Three Quarks Daily.