Teach Students Conservative Thought

The great thinkers on the right must be part of any syllabus that truly serves the next generation.

Polarization is at an all-time high. It can feel daunting—perhaps even misguided—to engage in meaningful dialogue with those holding starkly different views. What does it mean to champion pluralism in such a moment? Persuasion’s new series on the future of pluralism, generously supported by the Arthur Vining Davis Foundations, features essays and podcast interviews that make the case for civic dialogue and highlight inspiring examples of it in practice. You can find past installments here.

Political polarization tempts all of us to collectivize our enemies, blinding us to distinctions among those we consider opponents. Conflict over the university has not been immune to this tendency. Conservative proponents of viewpoint diversity sometimes describe humanities professors as an undifferentiated mass of illiberal bullies. Some on the left return the favor. Johns Hopkins professor Lisa Siraganian’s widely-read essays in Academe and the Chronicle of Higher Education, for example, describe the campaign for viewpoint diversity as “a MAGA plot.” By her lights, viewpoint diversity is the duplicitous rhetorical strategy of a conspiracy of politicians, plutocrats, and far-right professors determined to burn the university down.

To be sure, some on the right do want to burn the university down. But critics like Siraganian fail to distinguish between scorched earth right-wing culture warriors and the broad, politically ecumenical group of scholars—including some of her own colleagues—who want to bring more conservative perspectives into the curriculum in order to build the university up. This group isn’t carrying water for the Trump administration or trying to undermine academic freedom. They recognize, instead, that the quality of university teaching and research has suffered because of the neglect of conservative ideas, and are working to reintroduce such ideas to campus while respecting the best traditions of the university.

We consider ourselves members of this group, and have started an initiative to bring more conservative thought into college classrooms without imposing anything on anyone. Last spring, the two of us—a professor at a liberal arts college, Claremont McKenna, and a fellow at a center-right think tank, the American Enterprise Institute (AEI)—partnered to invite a politically mixed band of professors and think-tank scholars who teach courses on conservatism to help interested academics develop their own courses on conservative thought. The workshop attracted an ideologically heterogenous group of faculty, none of whom were enemies of academic freedom or looking to push a narrow political agenda. In fact, perhaps the only thing we collectively agreed upon is that the conservative intellectual tradition is worth teaching.

How did it go? If we had been looking to advance a MAGA plot, we would have had to count it a failure. While it’s true that conservatism—with its characteristic appreciation for the value of our civilizational inheritance, the fragility of moral and political order, the limits of human understanding, and the perils of revolution—furnishes students with critical tools to assess various left-wing enthusiasms, those same ideas provide students with critical distance on the MAGA right.

Giving students an occasion to discover the divergence between the depth of the conservative intellectual tradition and the shallowness of the contemporary online right is one of the major attractions of teaching conservatism for one of our session leaders, Emory’s Frank Lechner. Lechner said that one typical student “had expected a class dealing with the likes of Tucker Carlson and Candace Owens” but instead “got something much more interesting and serious.”

One reason is that conservatives are often, paradoxically, devoted to the liberal order. Partly because liberalism is our most important tradition, American conservatives are often consumed with preserving what is best in it, not burning it down like the online right. That also means many conservative intellectuals are hard to put into a tidy philosophical box. UNC’s Rita Koganzon, another of our seminar leaders, reported that teaching conservative intellectuals reveals “that no really good writer is merely conservative, just as none is simply a liberal. They all have strange, heterodox, often politically uncategorizable ideas.”

Conservative thinkers sometimes even embrace fashionable liberal causes for conservative reasons. For example, the agrarian conservatism of novelist Wendell Berry, an influential figure among young traditionalists, has driven him to engage in both anti-war and environmental activism. Conservatives can even embrace revolutionary change when they conclude that our institutions are so broken that there is nothing left to conserve. Hence, our workshop also exposed faculty to the work of Patrick Deneen, author, most recently, of the book Regime Change.

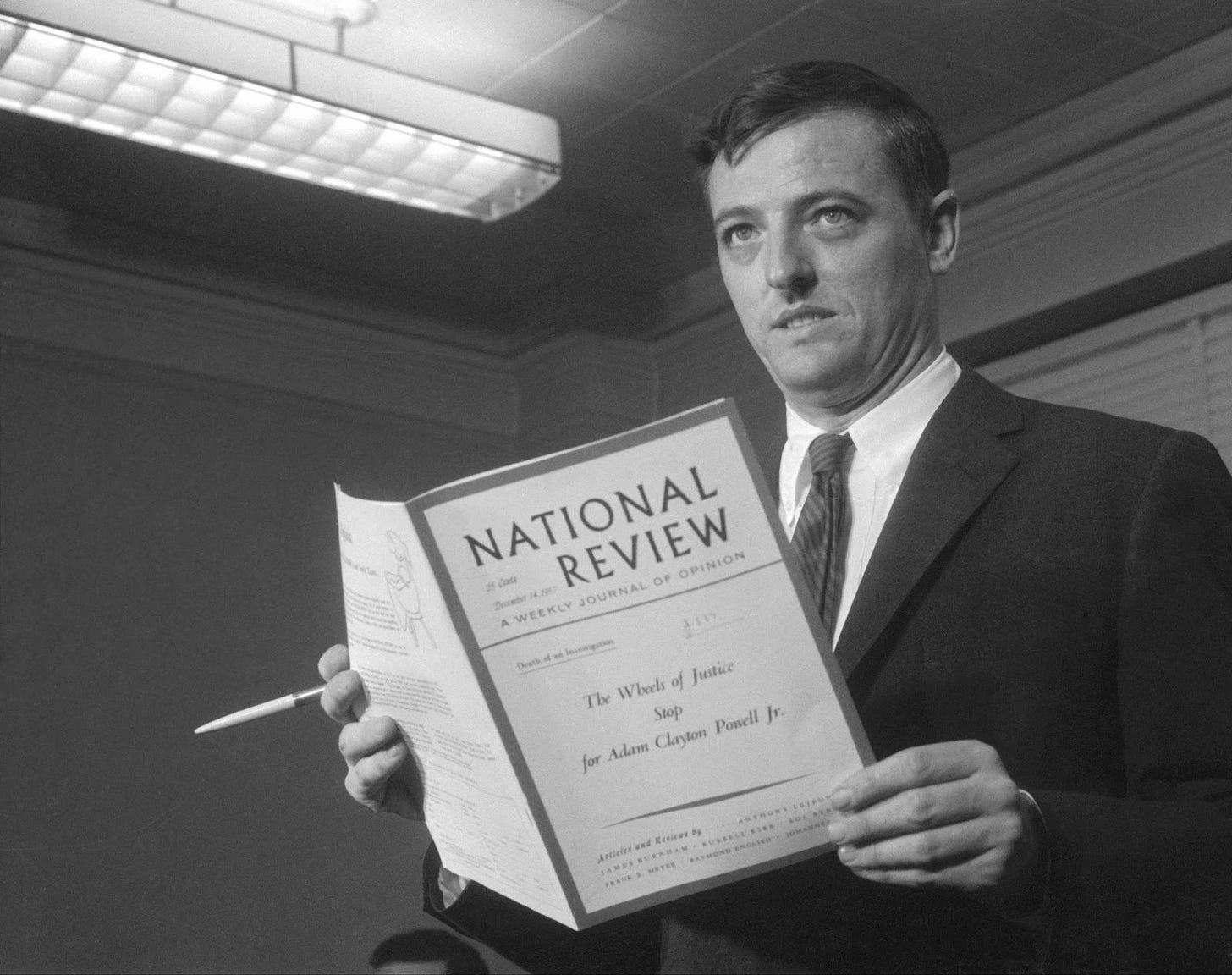

Indeed, in studying the breadth and intellectual history of conservatism, students invariably notice that it is not a narrow orthodoxy but a tradition enriched by deep internal tensions. While conservatives may share a common interest in preserving what is best in their inheritance, they often disagree over how to do so or even which inheritance should be conserved. A session with Stanford’s Jennifer Burns detailed one such tension in that history: The long-running intellectual and personal feud between the libertarian atheist Ayn Rand and the highbrow Catholic William F. Buckley. AEI’s Matthew Continetti, meanwhile, highlighted another: the hard fought tug-of-war between neoconservative intellectuals and the GOP’s more populist base.

Getting beyond a cookie-cutter vision of conservatism helps students see that what is most interesting in this tradition are not its reflections on the narrow question of how we should vote but its insights on the broad question of how we should live. Another of our speakers, Eitan Hersh, the founder of Tuft’s Center for Expanding Viewpoints in Higher Education, discovered how much studying conservative intellectuals meant to young people trying to sort their own lives out. This should be no surprise, since the conservative intellectual tradition addresses questions especially relevant to young people coming of age: Should I get married? Watch pornography? Have casual sex? Have children? Believe in God?

While conservative intellectuals have no monopoly on such questions, they have given answers that resonate with the intuitions of millions of Americans. Without engagement with this important strand of our intellectual inheritance, what Yuval Levin calls “civic self-knowledge” is impossible. No role could be more suitable to the university than to help the young people of our troubled country acquire such self-awareness. Even students who reject conservative arguments will be better citizens for understanding why they do and why others do not.

In other words, reintroducing intellectual conservatism to our universities will temper, not accelerate, our polarization. Today’s partisan spirit is a reductionist one: tell me if so-and-so is left or right, a squish or a solid, a friend or an enemy, and that’s all I need to know. The spirit of the university should be the opposite: it should lead one to follow the arguments implied by diverse political stances to the strange, profound, hard-to-answer questions with which every human being must wrestle in determining how to live.

In this way, a greater presence of conservative thought in the classroom can help universities do their essential educational work better. It might also help them recover some of the good will they have lost. Public trust has been declining in part because Americans believe the university has become too sectarian. And while this view is pervasive among Republicans, large numbers of Democrats share it as well. According to a recent Gallup survey, nearly a third of Democrats say that universities do a “fair or poor job” of “exposing students to a wide range of opinions and viewpoints.”

These concerns are not unreasonable. Very few university courses focus on American conservative intellectuals. As the political theorist Mark Lilla observed back in 2009: “A look at the online catalogs of our major universities [reveals] plenty of courses on identity politics and postcolonialism, nary a one on conservative political thought.” Research also shows that professors generally fail to teach a wide range of scholarly perspectives on the issues that most divide us. Even at the best universities, too many students graduate without being assigned a single article or book by any author who might even plausibly belong to this broad tradition.

The result is that even the most well-read academics are often innocent of viewpoints that contradict their milieu. Fairly late in life, for example, the NYU psychologist Jonathan Haidt stumbled upon conservatism by accident as he was browsing in a used bookstore. He started reading Jerry Muller’s excellent introductory essay in his anthology on conservative thought. By the time he hit the third page, he had to sit down right there in the bookstore to keep reading—the experience, as Haidt puts it, “literally floored” him. “I began to see [that conservatives] had attained a crucial insight into the sociology of morality that I had never encountered before.”

Unless students are assigned more authors like Muller, public trust in the university is likely to continue its descent for two reasons. First, a growing diploma divide is realigning our partisan loyalties, a trend that may well leave the next generation of Republicans even more estranged from higher education. Second, because younger cohorts of academics are more progressive on average than their aging peers, the university is poised to become increasingly dominated by leftists. As the political scientist Steven Teles noted, “a further drift leftward among the professoriate is already baked in.”

Without reform, the present partisan rift over higher education is on track to widen into a chasm. Such a future will likely include further rollbacks of tenure protections and more ham-handed legislative attempts to dictate what faculty teach. And more Americans will fail to benefit from higher education because they get the message that college isn’t welcoming for people like them.

To avoid this outcome, universities should work self-consciously to widen their intellectual horizons and build back the broad-based public support they enjoyed not so long ago. Their best response to the charge that they have become sectarian centers of leftist indoctrination is not guild-like defensiveness, but curricular reforms that make that stereotype less true. Such changes are the most authentic and enriching way for universities to respond to their present political travails: by using the resources of a serious but marginalized tradition of thought to deepen their internal intellectual life.

Jon A. Shields is a professor of government at Claremont McKenna College.

Benjamin Storey is a senior fellow in Social, Cultural, and Constitutional Studies at the American Enterprise Institute (AEI).

Follow Persuasion on X, Instagram, LinkedIn, and YouTube to keep up with our latest articles, podcasts, and events, as well as updates from excellent writers across our network.

And, to receive pieces like this in your inbox and support our work, subscribe below:

The famously ugly ex-sculptor who haunted the Athenian agora asking uncomfortable questions of so-called ‘experts’ some two millennia ago is supposed to have noted that the wisest among us are those who have a sense of how much they don’t know.

I recall one of those marvelous late-night college dorm discussions in which I participated upon my return to college just after I’d gotten out of the army in 1971. As expected, it ran quite a gamut. At one point it touched somewhat briefly on education. A guy who’d been quiet up until then spoke up. He said he thought that a good education should allow its recipients to ask serious questions in a number of essential areas, and then at least be able to have a good idea if the answers he/she was getting back were BS or not.

These two thoughts have guided my own thinking for that last 60 or so years of an 80 year old life, mostly spent teaching American history. I have no idea if I would be thought of as a liberal or a conservative, but I do know that I want to be thought of as an American; that is a citizen of the most extraordinary, the most crucial, the riskiest, and the most complex ongoing experiment in human society and government ever attempted, and to be worthy of that citizenship.

I have several degrees, and a focus on political theory during my PhD studies. I have never attended a university that didn’t include viewpoints from conservative intellectuals. This assertion that conservative viewpoints are not included in university curricula is just bogus. Yes, university professors are more liberal than the general public. It’s almost like advancing knowledge means you are willing to embrace change, which is—-gasp!— a liberal perspective.