The Constitutional Failsafe against Judicial Overreach

The Fourteenth Amendment was drafted as a check on the judiciary’s own power, argue authors Randy Barnett and Evan Bernick.

The Original Meaning of the 14th Amendment: Its Letter & Spirit

by Randy E. Barnett and Evan D. Bernick (Harvard University Press, 488 pp., $35)

Originalism arose as a theory of constitutional interpretation in the latter half of the 20th century. It began as a search for the “original intent” of the Framers and has evolved into a focus on “original public meaning,” which equates the meaning of a constitutional provision with how it would have been understood at the time of its enactment. Its early leading proponents—Edwin Meese, Robert Bork, and Justice Antonin Scalia, notably—framed originalism as a means of constraining the judiciary, which had run amok during the Warren Court era by finding “unenumerated” rights in the Constitution devoid of historical roots.

But what if an amendment, as originally understood, sought to protect unenumerated rights? Enter the Fourteenth Amendment. Drafted and ratified in the aftermath of the Civil War, it bars states from infringing upon citizens’ “privileges or immunities,” depriving persons of life, liberty, or property without “due process of law,” and mandates that all receive the “equal protection” of the laws.

Georgetown law professor Randy Barnett and Northern Illinois University law professor Evan Bernick have published a new book, The Original Meaning of the 14th Amendment: Its Letter & Spirit, that makes a compelling case that the Fourteenth Amendment protects not only the rights enshrined in the Bill of Rights from state infringement, but also unenumerated rights. As originally conceived, the amendment did so not by way of the due process of law clause—the means by which the Court protects unenumerated rights today—but rather via the amendment’s privileges or immunities clause. That clause states that “No State shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States.”

What are these so-called privileges or immunities? Barnett and Bernick persuasively argue that, while they include the protections of the Bill of Rights (which originally applied only against the federal government, not the states), they go well beyond them. In introducing the amendment in 1866, Senator Jacob Howard explained that the privileges and immunities of citizenship “are not and cannot be fully defined in their entire extent and precise nature.” Barnett and Bernick write that not a single member of Congress challenged this expansive gloss at the time. Instead, members made repeated references to Justice Bushrod Washington’s explicitly non-exhaustive listing of them in Corfield v. Coryell. Nor did Republican newspapers argue that the clause protected enumerated rights alone.

If they succeed in persuading that the Fourteenth Amendment protects unenumerated rights, Barnett and Bernick are less convincing with respect to how judges ought to determine which unenumerated rights warrant protection. They suggest

that if individual citizens have for at least a generation—that is, thirty years or more—been entitled to enjoy a right as a consequence of the positive constitutional, statutory, or common law of a supermajority of the states, it ought to be presumptively a privilege of U.S. citizenship.

But this standard seems arbitrary; it is not rooted in the provision’s text or even ratification history. Granted, this formula would better constrain the judiciary than much of current substantive due process analysis. Still, the decision to adopt a formula like that proposed by Barnett and Bernick in the first place strikes me more as a prudential, political judgment on the part of judges than one mandated by original meaning.

Perhaps this tension need not be resolved, though, because the Fourteenth Amendment was more of a grant of power to Congress than the courts. In other words, maybe the richness and indeterminate nature of the amendment’s original meaning and originalism’s desire for a constrained judiciary can be squared if we acknowledge that a distinct institution—Congress—might have been tasked with playing the prime interpretive role here.

Section Five of the Fourteenth Amendment empowers Congress to enforce its provisions (including the privileges or immunities clause) by “appropriate legislation.” As Stanford law professor Michael McConnell has written, Section Five “was born of the fear that the judiciary would frustrate Reconstruction by a narrow interpretation of Congressional power.” Still bitter from Dred Scott v. Sandford, the Reconstruction-era Republican Party did not have much faith in the courts to protect civil rights. In fact, the party’s martyr, Abraham Lincoln, had openly challenged the Court’s supremacy in interpreting the Constitution. He declared in his First Inaugural Address that if the Court alone had the final say as to “vital questions, affecting the whole people,” then “the people will have ceased to be their own rulers.”

It comes as no surprise, then, that the prime sponsors of the Fourteenth Amendment consistently and clearly framed the amendment as a grant of power to Congress. As he proposed the final version of the draft amendment to the House, Representative John Bingham told his colleagues that the amendment would empower Congress “to do that by congressional enactment which hitherto they have not had the power to do,” that is, to “protect by national law the privileges and immunities of all the citizens of the Republic.”

A robust congressional enforcement power was originally understood to apply to the due process of law and equal protection clauses as well. Indeed, Barnett and Bernick argue that the equal protection clause not only bars discriminatory state action, but also imposes “an affirmative duty on states to protect against violence by nonstate actors.” Therefore, “equal protection of the laws require[s] both proper protective laws and effective enforcement.” According to Barnett and Bernick, courts should announce that the equal protection clause imposes this affirmative obligation, and then leave Congress to enforce this protective duty against the states under its Section Five powers.

Therefore, the fact that one can quite literally get away with murder today in many American cities might amount to a federal constitutional violation. As Ryan Cooper wrote in The Week last year, in Philadelphia, for example, police make arrests in only about 40 percent of homicides. If you kill someone in the City of Brotherly Love, your chances of not even getting arrested are better than 50-50. Such underenforcement plagues Black communities in particular. Indeed, scholars like Harvard’s Randall Kennedy have long argued that “the principal injury suffered by African-Americans in criminal matters is not overenforcement but underenforcement of the laws.” Based off Barnett and Bernick’s research, this might amount to a constitutional violation: the Constitution may mandate that Congress take action to ensure that local and state authorities grant all citizens proper police protection. Defunding the police might not only be dumb, but also unconstitutional.

Barnett and Bernick’s tremendous book will likely give rise to a great deal of scholarship. My hope is that these scholarly responses will focus on Congress’s Section Five powers. Specifically, we need a stronger answer as to just how broad such powers are.

It seems fairly clear that the original meaning of the Fourteenth Amendment calls on Congress, not the courts, to play the lead role in (1) declaring which unenumerated rights warrant constitutional protection against state action and in (2) outlining responses to states’ failures to provide equal protection of the laws. Of course this congressional power is not unlimited—if it were, then Congress could alter the Constitution by “ordinary means.”

So, how much judicial deference is due toward Congress’ actions under Section Five? Overturning precedents that unduly constrain Congress’ Section Five powers based off flawed readings of the Fourteenth Amendment’s ratification history would better square with the amendment’s original meaning than the Court’s status quo, but that is only the first step. Further research is needed to pinpoint the precise standard under which congressional exercises of Section Five powers ought be reviewed by the courts.

Whatever that standard may be, allowing for a reinvigorated congressional role in deciphering the meaning of the rights of citizenship under the Fourteenth Amendment might help fans of originalism like myself have their cake and eat it, too: We can keep the judiciary constrained without letting that legitimate desire unduly cramp or narrow the Constitution’s rich original meaning.

And at this unique moment in our nation’s judicial politics, when many have either given up on originalism or want the courts to bend it to particular political ends, it might be wise for the Court to re-empower Congress and decrease the judiciary’s own power where the Constitution’s original meaning warrants such a move. This could help lessen pressures on the Court, redirect heated political debates toward the legislature, decrease judicial discretion, and most importantly, help us better adhere to the Constitution’s original meaning.

That strikes me as an all-around win.

Thomas Koenig, a contributing editor of American Purpose, is a student at Harvard Law School and author of “Tom’s Takes” newsletter. Twitter: @thomaskoenig98

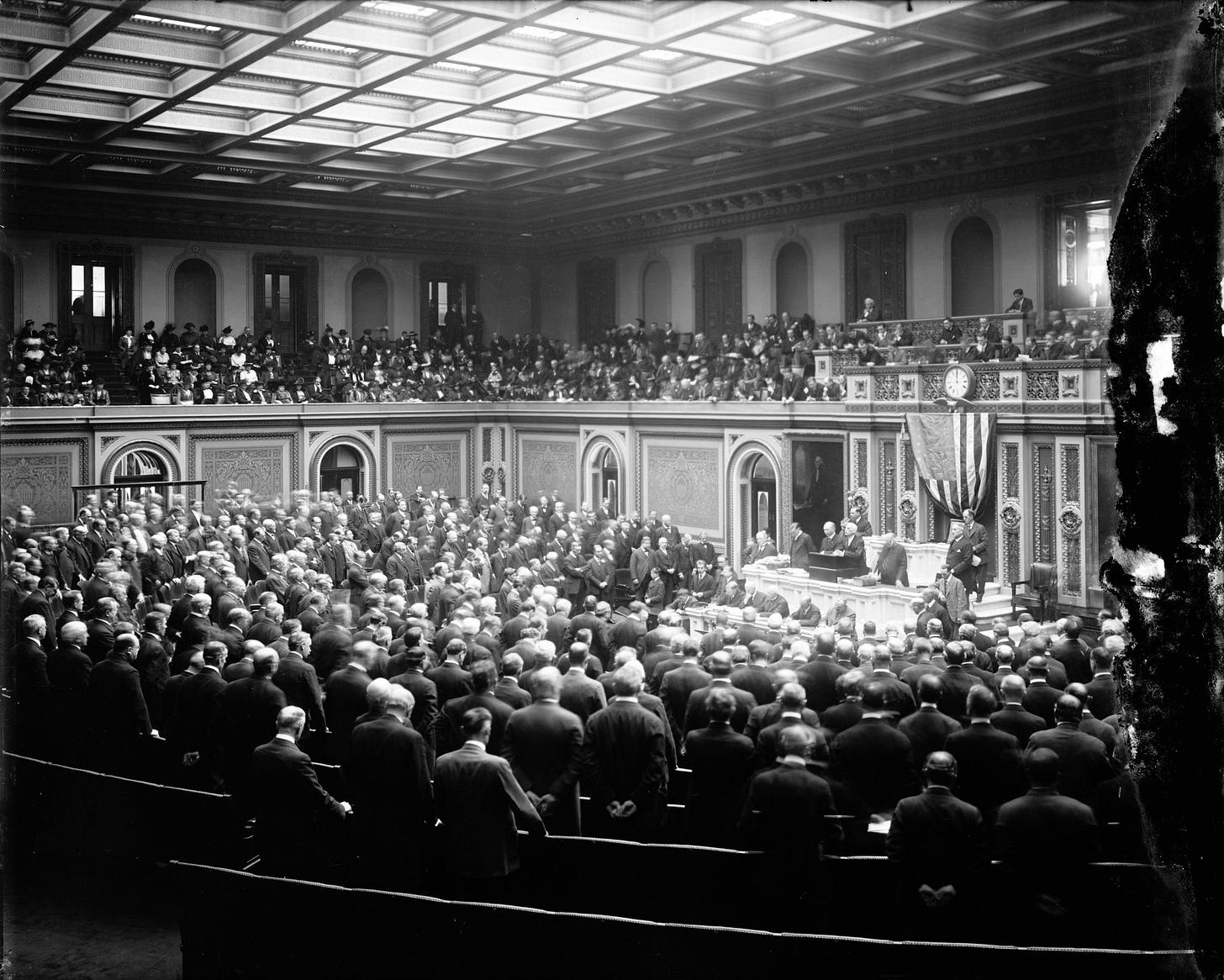

Image: Harris & Ewing photograph collection, Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C.