The Curriculum Wars

Public schools are not an ideological free-for-all. But any restrictions must be precise and constructed to avoid unintended consequences.

Recently, a county school board in Tennessee voted to remove the Holocaust graphic novel Maus from its curriculum, citing its profanity and nudity. On the other coast of the country, the Mukilteo School Board in Washington state removed Harper Lee’s To Kill a Mockingbird from its required reading list, partly because it includes racial slurs. Near the nation’s capital, one Democratic member of the Virginia State Legislature called for Fairfax County Public Schools to stop teaching the graphic novel Persepolis in its classrooms, due to his concerns that the memoir is Islamophobic. More broadly, legislatures across America are considering and passing laws to circumscribe how and when public school teachers can teach their students about topics like race, gender, and sexuality.

It would be easy to look at these developments and conclude that there’s a massive wave of state-sponsored censorship that’s coming from both the left and the right. But that would be misunderstanding the nature of public schools.

Public schools are not a marketplace of ideas. They’re government-controlled institutions paid for by taxpayers; with few exceptions, we’re required to send our children to accredited schools and we expect schools to impart a range of skills and knowledge that align with our values and interests. There is no “free speech” case for a kindergarten teacher showing their children the ultra-violent film Kill Bill; alternatively, few would argue that it would be appropriate or responsible for a high school science teacher to tell their students that Bill Gates is using COVID-19 vaccines to implant them with microchips.

Teachers only have a limited amount of time to teach concepts to students and must use that time wisely by curating the best classroom material. School boards, legislatures, and state departments of education typically work together with teachers and administrators to decide what’s appropriate to teach students and what isn’t. In my state, the expectations for what to teach students are drafted by the Department of Education, which compiles what are called the Standards of Learning. Teachers are expected to impart the skills and knowledge listed to all of their students.

These processes don’t apply just to pedagogy about hot-button issues like race or gender; what sort of mathematics education should be offered to children and what shouldn’t can be just as fiercely debated. Public schools aren’t and shouldn’t try to be value-neutral; what’s taught in schools is a democratic decision—not a free-for-all.

That being said, public officials who are helping shape curriculum and lay out the guardrails for how educators should be teaching various topics should be careful about how they legislate on these topics. Not every intervention is needed or well-structured. While I won’t try to tell every district in America exactly how it should teach every topic—our federalist system means that education is handled at the local level, and conservative and progressive districts will never teach things the exact same way—here’s some helpful advice for how our public officials should think about regulating curricula and instruction:

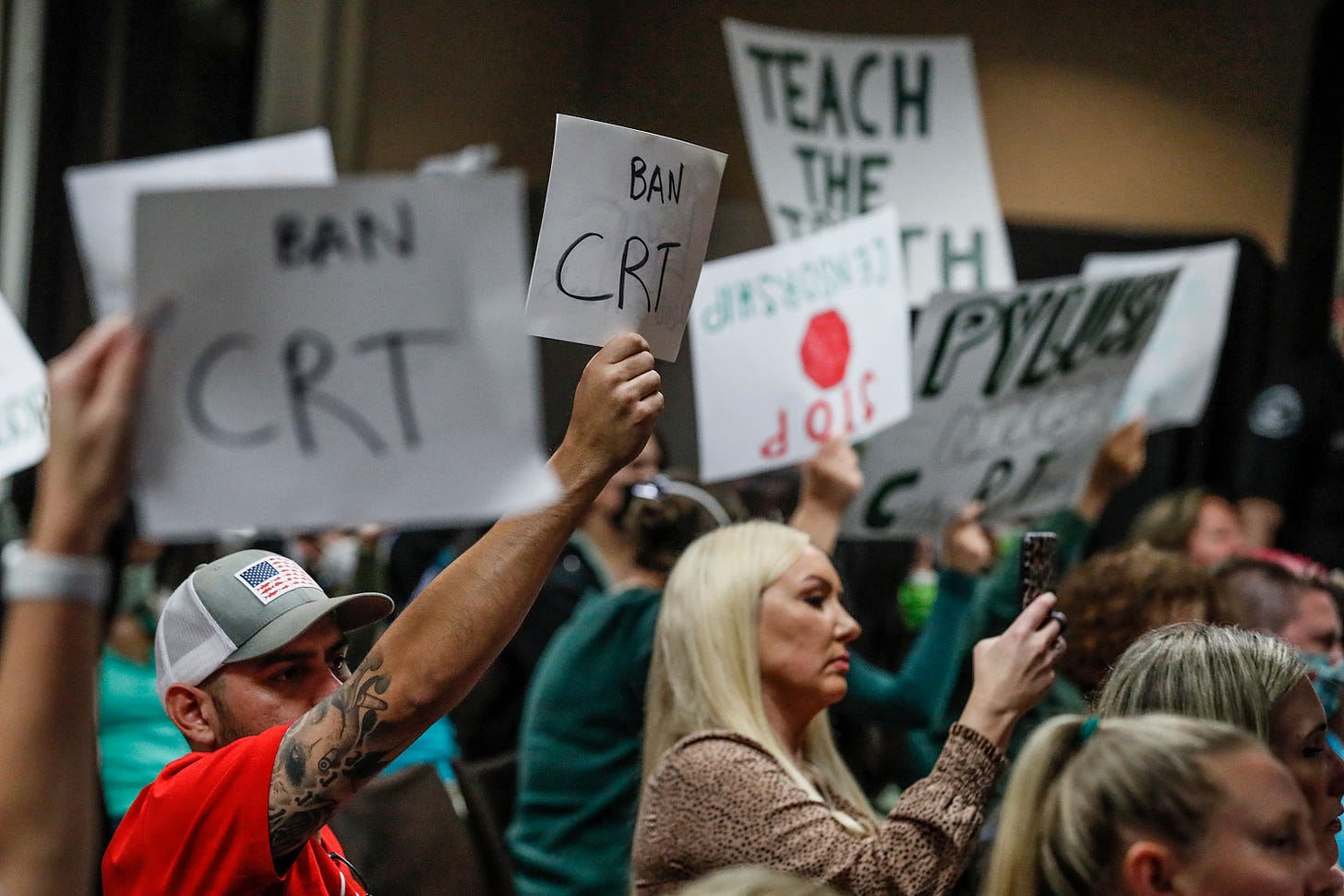

Craft Narrow and Precise Guidelines About Race for Teachers: Over the past year, we’ve seen mostly conservative-led legislatures dive into the debate over “critical race theory.” Although CRT, which is a legal theory, is not directly taught in most public schools, CRT-inspired racialism has found its way into some instruction, troubling some parents who worry that it is leading to their kids being stereotyped or racially discriminated against by instructors.

The best way to tackle this challenge through legislation is to write narrow and precise bills that make clear that teachers have a free hand to teach about historical and contemporary racism but shouldn’t engage in racial generalizations. An Idaho law on race in schools is clear and simple, with the relevant parts stating that schools shouldn’t “direct or otherwise compel students to personally affirm, adopt, or adhere to [the belief that] any sex, race, ethnicity, religion, color, or national origin is inherently superior or inferior” or the belief that “individuals, by virtue of sex, race, ethnicity, religion, color, or national origin, are inherently responsible for actions committed in the past by other members of the same sex, race, ethnicity, religion, color, or national origin.” A Texas law, on the other hand, deals with racialism in public schools with similar language as the Idaho law—but then goes much further, saying teachers “may not be compelled to discuss a widely debated and currently controversial issue of public policy or social affairs” and that teachers who choose to discuss one of these topics “shall explore that topic objectively and in a manner free from political bias.” What counts as a controversial issue? Can a legislature really determine whether teachers are teaching these issues objectively? The law is far too broad and confusing to be effective. Instead, the simpler the law is, the easier it is for teachers to understand it and comply with it.

Champion Transparency the Right Way: Another conservative response to rising racialism in public schools has been to promote a wave of bills that would require greater transparency. Although the details of these laws differ, they all focus on mandating that instructors post instructional materials online. Disappointingly, Democrats and even organizations that have historically supported transparency like the ACLU have refused to support any version of these laws—apparently fearful that if parents found out more about what schools are teaching, they would demand changes. But the lawmakers sponsoring these bills should also think about unintended consequences. Some of the bills out there simply instruct schools to post their materials online. The problem is most teachers don’t want to be inundated with complaints from busybodies on the other side of the country—people who don’t even have kids in their classroom. A 2014 Ohio law provides a good alternative for transparency advocates by allowing parents to request instructional materials, curricula, or reading lists through the local school board. Transparency bills could simply require school districts to give parents in each district access to a website where they could log in and view materials, making it much harder for professional activists to hassle teachers while giving parents the accountability they deserve.

Acknowledge That Higher Education Needs Academic Freedom: Texas Lt. Governor Dan Patrick recently proposed ending tenure for new hires in the University of Texas system as one way to combat the embrace of critical race theory. This misunderstands the role of higher education. While most Americans don’t want the public schools they pay for and are required to enroll their children in to teach every idea under the sun, universities play a very different role. Unlike public schools, we’re not required to send our kids to college; unlike public schools, colleges and universities are not directly controlled by the government. We want our academics to have as much academic freedom as possible so they can conduct cutting-edge research and engage in needed debates. Yes, this means tolerating the occasional academic way out on the extremes of the left or right. But when the Wyoming Senate recently voted to eliminate gender studies courses at the University of Wyoming, they created a precedent whereby the state legislature directly controls the instruction at public universities. This sets off a slippery slope that is unlikely to end well, especially for conservatives, who are already an embattled minority on campus.

Don’t Just Subtract, Add: While it’s appropriate for public officials to set guidelines about what isn’t acceptable to compel public school students to learn, that’s just step number one. Lawmakers should also think hard about what we do want our kids to be learning and make sure they are being taught that information. Illinois offered a great example last year when it passed a mandate creating an Asian American history requirement in public schools. Furthermore, some states, like Florida, have mandates in law requiring the public K-12 system to instruct their students on “the history of African Americans, including the history of African peoples before the political conflicts that led to the development of slavery, the passage to America, the enslavement experience, abolition, and the contributions of African Americans to society.”

School wars are nothing new. Since the inception of the public school system, we’ve had fierce debates about how we teach our kids—including arguments about intelligent design, sex education, and whether or not defending the Alamo was “heroic.”

Let’s not kid ourselves that schools are supposed to be an ideological free for all. Everybody has something they wouldn’t want their child to be forced to learn at the cost of their taxpayer dollars. But as we’re regulating what goes on in our schools, let’s be precise and narrow, anticipating unintended consequences of overly broad legislation.

Zaid Jilani is a frequent contributor to Persuasion. He maintains his own newsletter where he writes about current affairs at inquiremore.com.

I largely agree with your take on these matters, which is well expressed here. I would add, though, that in weighing the competing interests and responsibilities of parents and the State in rearing citizens (and you correctly note that we're talking about child-rearing, not just education), sex is generally considered way to the parents' side -- especially at such a young age.

It's significant, too, that there's not a lot of fundamental disagreement in today's America about issues of race and equality, but there's a very large segment that prefers, to a greater or lesser extent, traditional sexual mores. For a teacher to tell his students that, say, "all kinds of love are equal" and answer the the parents' outrage with "What? What'd I say?" is either disingenuous or -- more likely -- obtuse.

I primarily agree with Mr. Jilani's well-written article and his proposed ways to resolve these issues. Parents have to be involved, and as a parent I always kept informed of what was going on in the school my child attended. "Erudit0rum" above posted clearly why so many of these decisions have to be kept private at some levels, so we can all live and work together, considering our divergent values and beliefs in this country. When I was in elementary/middle school, my parents attended the parent screenings and discussions of films to be shown on sex and drug information. I always had permission to attend (parental permission was required), but my parents had already educated me on most of what was in sex education films so they were mostly reinforcements of what I had already been taught at home. To my surprise, many of my peers were not that fortunate and didn't know even the basics from their parents, and so it is sometimes necessary for parents to be reawakened to their responsibilities as a parent and as a parent of a public school attendee. If public sector schools push curriculum on parents or students, there will be many more local board elections with parents taking leadership and private education may grow and appeal to more parents as the demand grows.