The Day Merit Died

The Trump administration wants a civil service based on politics, not skills.

This article is part of an ongoing project by American Purpose at Persuasion on “The ‘Deep State’ and Its Discontents.” The series aims to analyze the modern administrative state and critique the political right’s radical attempts to dismantle it.

To receive future installments into your inbox—plus more great pieces by American Purpose and Francis Fukuyama’s blog—simply click on “Email preferences” below and make sure you toggle on the buttons for “American Purpose” and “Frankly Fukuyama.”

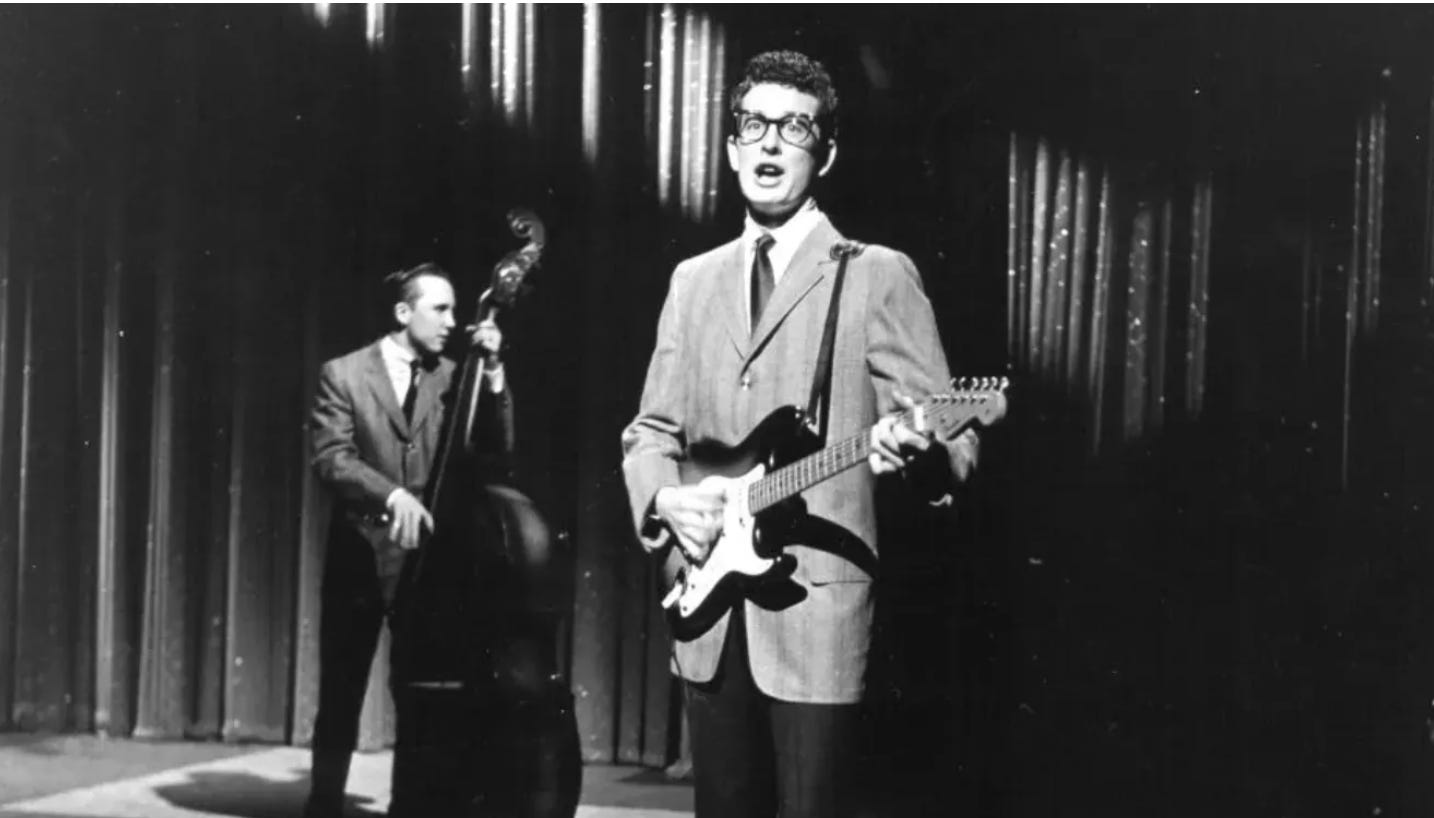

Rock music fans know February 3, 1959, as “the day the music died,” when three legends of the genre perished in a plane crash. Now July 17, 2025, might well go down as the day the cherished merit system for federal employees died.

That might seem hyperbolic but, in two different actions, the Trump administration asserted the right to fire any employee, at any time, for any reason; and the authority to hire an unlimited number of political appointees, for any agency, for the life of the administration.

Since the passage of the Pendleton Act in 1883, the federal merit system focused on hiring on the basis of merit and minimizing political interference in the work of federal agencies. Ever since, those principles have had remarkable bipartisan support, through wars and domestic crises—until the Trump administration. Those principles evaporated on July 17.

On firing: attorneys from the Justice Department told an administrative law judge at the Merit Systems Protection Board that the Constitution gives the president the authority to fire employees without cause, at will, at any time. (The MSPB was established by Congress in 1978 to hear appeals by civil servants who believe their rights have been violated. For half of the last decade, the MSPB has operated without a quorum of its three board members. Every time there is no quorum, cases on appeal back up. That’s a special problem in 2025, because thousands of new cases have piled up at the board because of the Trump administration’s decisions—far more than is normally the case.)

This is an argument that’s been bubbling in the backdrop of the administration since January 20. Conservative activists have read Article II, Section 1 of the Constitution, “The executive Power shall be vested in a President of the United States of America,” to mean that the president has full power over the conduct of the executive branch.

At 3:00 pm on January 20, Jill Anderson, a staff attorney at the Department of Justice, received an email saying she was fired. An hour later, she was locked out of the department’s computer systems, and her mobile phone was wiped. The same thing happened to at least three other Justice career officials.

In March, the department fired its top pardons attorney, Liz Oyer. It was her case that prompted the case before the MSPB. On July 15, she posted on her Substack, “It’s all part of a master strategy to clear the way to install loyalists throughout government.”

Lest you think that’s an exaggeration, on July 17, the White House issued an executive order creating a new “Schedule G” in the public service, giving the president the authority to create “positions of a policy-making or policy-advocating character normally subject to change as a result of a Presidential transition.” (Fans of personnel minutiae will remember the lore of Schedule F from the end of the last Trump administration, which transformed itself into Schedule PC—Policy/Career—to give political leaders the power to transfer employees whose jobs dealt with policy into a new schedule and, from there, make it easier to fire them. Schedule G is the next one in order.)

The executive order says it focuses on “improving the operations of the Department of Veterans Affairs.” But that could easily be just a crack in the merit system door. Is it likely that other cabinet secretaries would not soon see the need for their own flexibility in improving their operations? The framework of the executive order, moreover, would not constrain Schedule G to just the VA.

Neither of these actions is yet cast in constitutional concrete. But in firing federal employees, the Trump administration is taking pains to bend the MSPB to its will, although it does not now have a quorum for action. If the lack of a quorum continues, however, the losing side in the administrative law judge case will certainly appeal to the federal courts, where it would probably find its way to justices increasingly friendly to Trump’s interpretation of executive power.

And in hiring political appointees, the administration has already stretched its power to create new civil service schedules. The administration’s direction to OPM is clear—make it easier to hire political appointees—so the path forward is just as clear. This case, too, is destined for the federal courts, but the same outcome is likely.

Among the world’s democracies, the U.S. federal government already ranks at the top in the number of political appointees—about 4000, 1200 of which require Senate confirmation. That’s vastly more than in, for example, Germany or the UK, which each count fewer than 200. And, to make things worse, the research shows that “Programs and agencies run by political appointees tend to perform worse than other programs and agencies,” as reported by political scientist David E. Lewis.

In the interregnum between 2021 and 2025, personnel wonks like me focused on the second coming of Schedule F. Now, six months into the second Trump term, that is relatively small potatoes compared with the broad, sweeping actions which aim to eliminate the traditional protections of federal civil servants and to increase the number of political appointees.

It would be easy to chalk this up to Trump’s effort to bring back the spoils system, but it’s far more insidious. It’s a careful strategy to shrink the government and to replace its workers with employees who can be counted on to be loyal to the Trump cause. This isn’t a strategy aimed solely at strengthening the Trump hold on the bureaucracy but rather one aimed at permanently shifting its base—a kind of administrative gerrymander.

Never in the history of the country have such massive changes come to the federal workforce in such a short time. The system of hiring people for what they know and protecting them while they do their best in exercising that knowledge might not yet be dead. But it’s dying.

Donald F. Kettl is Professor Emeritus and Former Dean of the University of Maryland School of Public Policy. He is the author, with William D. Eggers, of Bridgebuilders: How Government Can Transcend Boundaries to Solve Big Problems.

Follow Persuasion on Twitter, LinkedIn, and YouTube to keep up with our latest articles, podcasts, and events, as well as updates from excellent writers across our network.

And, to receive pieces like this in your inbox and support our work, subscribe below:

The day merit died was 1981 when the Carter Administration agreed to settle Luevano vs Campbell eliminating the objective test of the Professional and Administrative Career Examination (PACE), a written test used by the Civil Service Commission to screen candidates for federal employment. Ever since then Federal Employment hiring has been subjective, ie political. Many see much of the hiring as leaning far left. Now you object to a subjective, ie political basis for for firing to correct some of that leaning. You also forget that it was Joe Biden and Ted Kennedy who introduced pure politics to the selection of Federal Judges by totally politicizing the appointment of the Robert Bork. As you so so shall ye reap.

Is anyone surprised?

They shouldn’t be. The one thing Trump learned all too well in his first term was the nature of the obstacles he faced both in implementing his agenda and in avoiding sanctions for his illegal and unconstitutional actions. Much of what he’s attempted in Trump 2.0 is aimed at neutralizing of eliminating those obstacles. With the help of the John Roberts cabal, his lickspittle Cabinet, and subservient Republican legislators he is accomplishing both. All of this was easily foreseen.