The Democratic Socialists of America Are Rejecting Democracy

DSA members are choosing to stand with a dictator instead of the Venezuelan people.

This article is brought to you by American Purpose, the magazine and community founded by Francis Fukuyama in 2020, which is proudly part of the Persuasion family.

“I want to be clear on where I stand. I believe both Nicolás Maduro and Miguel Díaz-Canel are dictators,” said Zohran Mamdani per a statement issued by his campaign to the media shortly after an appearance on The Moment podcast with Paola and Jorge Ramos. When questioned about his perception of both Latin American rulers, Mamdani had responded in a much milder manner, stating that Maduro’s government had been “one of repression” and that he had not thought much about Díaz-Canel’s tenure. His clarification brought relief and hope to many Venezuelans and Cubans who have fled tyranny to find a home in New York City. It seemed like his words would open a new chapter in the political organization he has belonged to since 2017, one in which separation of powers, respect for human rights, and free and fair elections would be at the forefront of its philosophy.

Others in the same organization that I’ve befriended since I moved to New York have—just as Mamdani did last year—assured me that they condemn the crimes Chávez and Maduro have committed against my compatriots and that they do not see the movement they headed as a model. But a livestream hosted on the Democratic Socialists of America’s main YouTube channel on January 6 calling for protests against Maduro’s capture has left me with the following conclusion: they are not democratic.

“Stand in solidarity with President Maduro, with the First Lady,” says DSA member Luisa Martínez—who was part of a delegation that met with Maduro himself in 2021—at the beginning of the recording. She briefly goes over the meeting’s agenda and continues with a list of demands that, she insists, DSA members and supporters should make to U.S. elected officials: (1) free Nicolás Maduro and Cilia Flores immediately, (2) pass the War Powers Resolution in Congress, (3) impeach Donald Trump over his strikes in Venezuela, (4) “no war for oil,” and (5) end all Venezuela-related sanctions. Strikingly, no mention is made regarding the demands that Venezuelans have made to Maduro throughout the years for greater democracy.

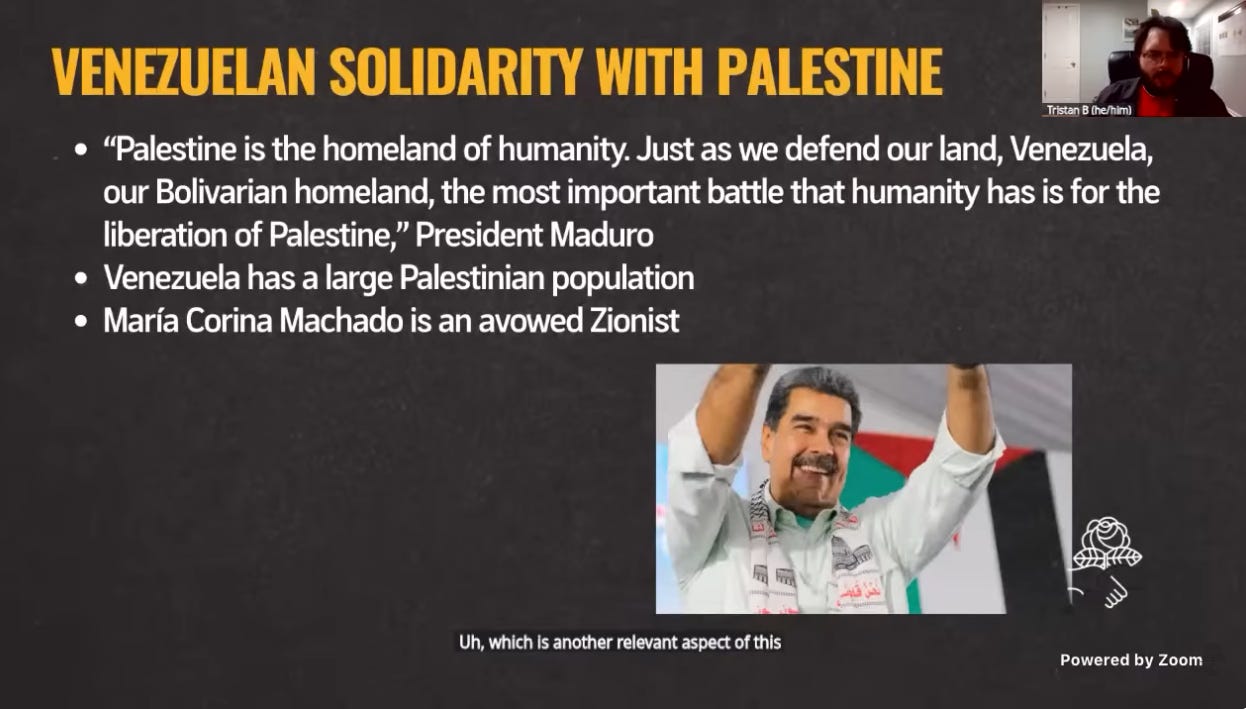

The mic is passed on to Tristan Bavol-Marques and Savannah Kuang to give a brief lesson on contemporary Venezuelan history. Both have been to Venezuela and promoted messaging in support of Maduro’s regime. Bavol-Marques was present in 2022 for the International Summit Against Fascism—a quite ironic name, for the rabidly nationalist, military-directed government that has ruled over Venezuela has often been described by its citizens, especially by late democratic socialist leader Teodoro Petkoff, as fascistic.

Kuang was accredited to observe the 2024 presidential election, whereas high-profile international observers, including those in neighboring Colombia, were denied entry to Venezuela at the last minute. Despite the clear-cut evidence that opposition politician Edmundo González had won—certified by the long-standing electoral monitoring organization the Carter Center, among others—she parroted the claims of Maduro’s cronies that he had won the election in her report back to her fellow DSA members.

Bavol-Marques and Kuang begin by explaining, in their view, what the United States wants with Venezuela. As expected, they mention oil, but they also say that the United States has combated Chavismo “to crush any hope of twenty-first century socialism,” to set an example of sorts following the fall of the Soviet Union.

They move on to discuss the Caracazo, a series of protests and lootings that followed the austerity measures passed by President Carlos Andrés Pérez in 1989, which were heavily repressed by Venezuela’s security forces after lasting for six days: an event Venezuelans remember with shame. There are, nonetheless, important mistakes in how they frame this event. For example, they call Pérez’s government a right-wing one, failing to mention that he led the nationalization of the oil industry in the seventies, and that his party belongs to the Socialist International. I was pleasantly surprised that, as they moved on to talk about the rise of Hugo Chávez—Maduro’s predecessor—and his political movement, they acknowledged that he first attempted to reach power through a failed military coup.

Yet they proceed to say that he “[used] oil wealth to fund expansive social programs to benefit the poor of Venezuela,” which “[drew] ire from [the] U.S. Empire.” These claims overlook the admirable growth and social mobility Venezuelans experienced during most of the twentieth century due to oil-funded programs of those years, such as the Gran Mariscal Ayacucho scholarships put in place by Pérez’s first government. This program allowed many from working-class backgrounds to pursue graduate studies in the United States and share their expertise with folks back home. Later on, they talk about the short-lived coup of 2002, an event that Chavistas still invoke today to demonize opposition figures and movements, even if the vast majority did not participate in that episode.

Then they move onto what they consider to be two successes of the Bolivarian Revolution: Misión Vivienda and the communal system. The former, a program that was purported to allow working-class Venezuelans to live in affordable, dignified housing, has been widely seen as a failure in the country. Bavol-Marques says that through Misión Vivienda, a million quality homes have been built, yet these have had widespread structural defects such as filtrations and unstable walls; beneficiaries have not been given property titles, making them vulnerable to evictions if found to disagree with the politics of Chavismo; and houses have been built under opaque contracting conditions marked by missing funds and inflated figures. As for the communes, which they present as decentralized units that allow for a more horizontal mode of governance: these are councils led by governing party members and closely watched by colectivos—pro-Chávez paramilitary groups—that have allowed for more efficient top-down control of working-class neighborhoods.

Neither Misión Vivienda nor the communal system are proof of poverty-reducing, democratic governance. On the contrary, they are proof of rampant corruption and carelessness and the authoritarian tactics that Chávez and Maduro have enacted.

Kuang gives a brief overview of sanctions that have been applied to the Maduro dictatorship. But the sanctions on Venezuela’s oil industry that many on the Left have pointed to as the cause of the suffering of Venezuelans were imposed only in 2019, whereas the humanitarian crisis began in the mid-2010s.

After Bavol-Marques and Kuang end their presentation, other DSA members hop on the livestream to state their support for the campaign in favor of Nicolás Maduro’s release. While this part is less substantial, one detail is particularly irksome: New York City Council Member Alexa Avilés claims that eighty civilians died in the strikes of January 3, which is a blatant lie. So far, two civilian deaths have been confirmed; the rest have been military officers, including thirty-two of the Cuban agents who made up Maduro’s security ring.

Let me be clear: I do not believe that every DSA sympathizer or member is necessarily against democracy. Out of concern over past U.S. mishaps abroad and growing inequality within America’s borders, many have found this organization enticing. Nonetheless, as long as they do not question the legitimacy of Maduro’s dictatorship, nor point out the corruption and authoritarianism that has defined Chavismo since its early days, they do not stand with the Venezuelan people; they are standing with authoritarianism. In any case, the folks who hosted this livestream undoubtedly are, I insist, not democratic. And as long as they hold authority within the DSA over this issue, it is quite difficult for Venezuelans to take their purported commitment to democracy seriously (especially progressive Venezuelans who have suffered the brunt of Maduro’s dictatorship).

“This blatant pursuit of regime change doesn’t just affect those abroad, it directly impacts New Yorkers, including tens of thousands of Venezuelans who call this city home. My focus is their safety and the safety of every New Yorker,” posted Zohran Mamdani on X the day of Maduro’s capture. I can only wonder: is Mamdani that disconnected from the suffering of Venezuelans who find themselves in a vulnerable situation in the United States precisely because of Maduro and his cronies, who now dream of going home because of these recent events? Has he not read the indictment of the Southern District Court against Maduro—a legally solid one, per The Atlantic—which showcases how his actions have threatened the safety of New Yorkers? Is he caving in to the still-not-severed ties between the Democratic Socialists of America and the violent, corrupt caste that has plunged Venezuela into ruin? Many Venezuelans in New York, including myself, have expressed our willingness to talk to anyone about this issue, yet as far as I know, no effort from the mayor to reach out to the community has been made.

Hopefully, DSA members with their hearts in the right place will speak out against this perspective and pressure their leaders to stand with the Venezuelan people. If not, left-leaning Americans should realize the dangers of this organization and stand with Venezuelans and their dreams of dignity.

Carlos Egaña is a Brooklyn-based Venezuelan writer and educator.

Follow Persuasion on X, Instagram, LinkedIn, and YouTube to keep up with our latest articles, podcasts, and events, as well as updates from excellent writers across our network.

And, to receive pieces like this in your inbox and support our work, subscribe below:

Socialism is an authoritarian ideology. It is not a system of government. There is a good reason that Marx called for a dictatorship of the people. The key word is dictatorship.

Thank you for an excellent essay.