The Enduring Fierceness of American Politics

Ahead of tomorrow's pivotal election, it's easy to lose track of just how heated things have gotten in the past.

There’s not much that’s better about lockdown life, but at least here on the 1000-acre Bard College campus, time for more walking is one of them. My daily yomp takes me past the beautiful Frank Gehry concert hall and then through the country cemetery where, right opposite Hannah Arendt, the novelist Philip Roth is buried.

Roth is exactly the kind of dead, white, male writer who has gone out of fashion recently, but he still has things to teach us about the American character. There in the last novel in the Nathan Zuckerman series, Exit, Ghost, is a reminder about how seriously Americans take politics but also that we ourselves do not in fact live in unprecedented times.

On the morning after George W. Bush won the 2004 election, Zuckerman phones an acquaintance who answers the call by announcing “Caligula wins.” Anguish, bafflement, panic are all around, the acquaintance reports. People are on the steps of the New York Public Library crying. Zuckerman the “onlooker and outsider” was familiar with the “theatrical emotions” that politics inspire. “You’re heartbroken and upset and a little hysterical,” he observes, or “you’re gleeful and vindicated for the first time in ten years, and your only balm is to make theater of it.”

It has become the conventional wisdom of the Trump era to say that these days are without equal. Even the early comparisons to President Andrew Jackson have receded into the rear view mirror. Yet our contemporary theatrical emotions are hardly unique in the context of history. That is not to say, of course, that political discourse over the last four years has not had its own unique elements, or that these elements have not excited the most extreme responses. Clearly Donald Trump is something new. Rather, and I say this respectfully as a non-citizen, non-voter, that historically speaking American politics has always been a complete trainwreck. That’s why none of us can ever look away.

Tocqueville was one of the first to be transfixed by democracy in America, but he certainly wasn’t the last. People all around the world have been endlessly, addictively fascinated by American politics for the past 200+ years. Sometimes I think that Americans forget how unique their politics are, not least those surrounding presidential elections. Growing up in Britain and then living in Ireland, I can report that at general elections in both those countries—each with a distinct and vibrant political culture—a certain weariness always seems to set in during the campaign, which anyway usually only takes four to six weeks. Even political commentators, who are paid to be interested, tell readers and viewers that they’re bored.

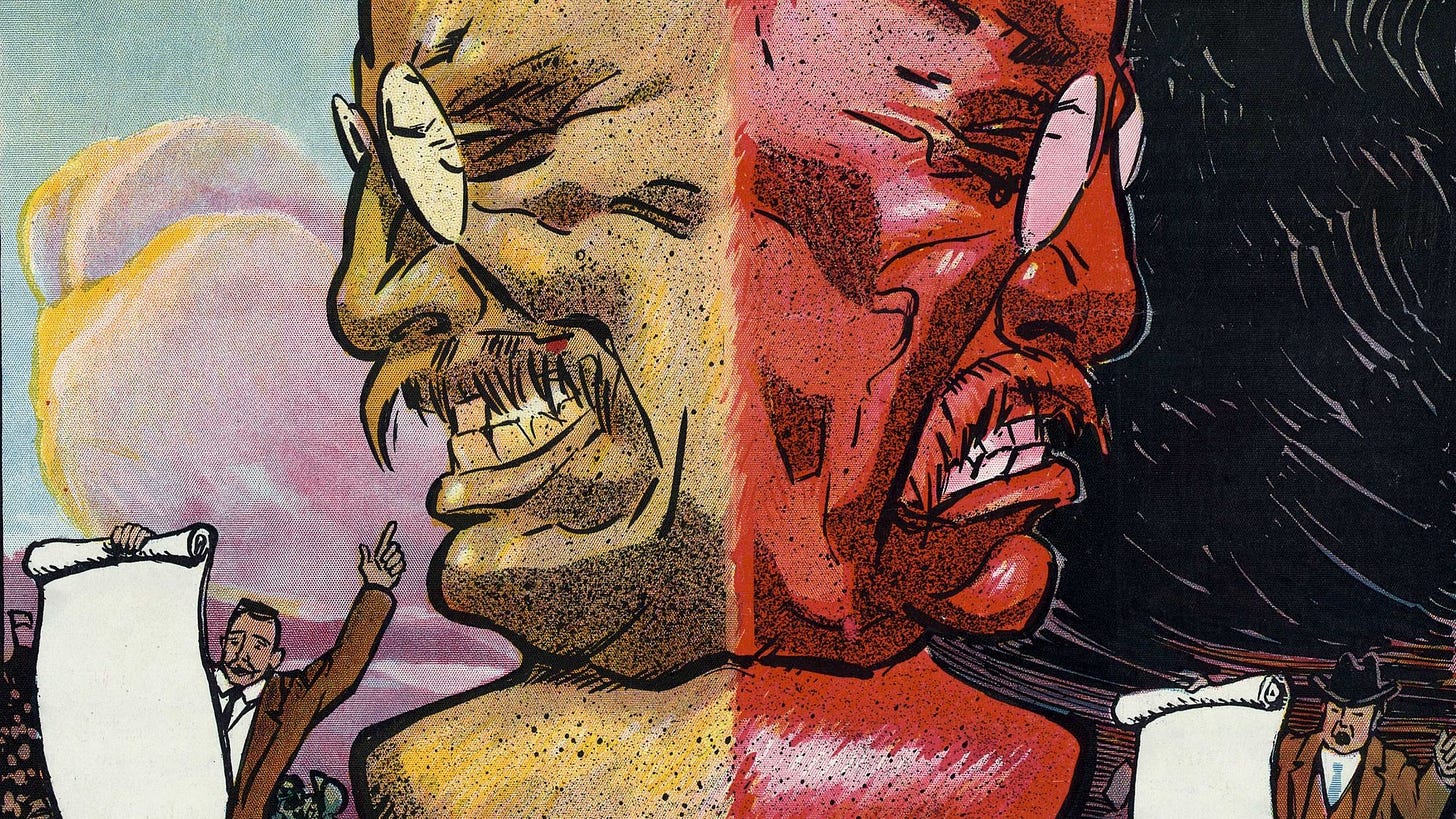

American politics is different. The long race consumes us. Partly it's the sport of the thing. The one-on-one nature of the presidential contest encourages a prize-fighting quality that even the two contestants seem powerless to resist (although in Joe Biden’s case the strategy has been “rope-a-dope.”) Mark Salter in his new memoir-biography of John McCain recounts the Arizona senator trying to change the pugilistic narrative by suggesting to Barack Obama in 2008 that the two men travel around the country together on the same plane to undertake a series of joint town hall meetings. That idea got short shrift and instead McCain, a former media darling, found himself cast as an extremist and even a racist. Like the scorpion crossing the river on the frog’s back, a presidential election just can’t help its nature.

But the Trump era is different, you protest! All norms have broken down. Civic discourse has collapsed. Rhetoric is poisonous. The dignity of the presidency has been shredded. You can make up your own minds about the successes and failures of the last four years, but in reality the politics itself is really not so different.

Even a quick pop quiz of American history illustrates the point. Norms trashed in an unprecedented fashion? FDR, who was regularly compared by his opponents to Hitler and Mussolini, happily brushed aside a century and half of tradition in the 1940s by standing a third and fourth time for president; after his death, Congress passed the twenty-second amendment to stop it happening again. Vulgarity and behavior unbecoming of the Commander-in-Chief? LBJ literally took meetings while seated on the can, often with the door left wide open. John F. Kennedy had the secret service smuggle his mistresses into the West Wing and used the White House swimming pool for more than his daily exercise routine. Bill Clinton did, in fact, have “sexual relations” with an intern in the Oval Office. Ideological purity tests and witch hunts? Try postwar McCarthyism. Politicization of the supreme court confirmation process? Look back to the Robert Bork nomination. The political violence of our era pales with what Arthur Schlesinger Jr called “the decade of hate” in the sixties—a time when assassins murdered the 35th president of the United States, his brother Bobby Kennedy, Martin Luther King, and Malcolm X; when the Vietnam War ripped the country apart, and political protest, often violent, regularly took over the streets and campuses of the United States. Secrecy and misinformation about the president’s health is nothing new either. During the last global pandemic Woodrow Wilson had a stroke that incapacitated him to such an extent that for the remaining year and half of his presidency he was often unable even to speak. FDR as president kept his wheelchair hidden from public view. JFK concealed Addison's Disease as well as the crystal meth he took to dull the pain. As to the chivalrous traditions of politics in another age, try rereading Allen Drury’s Pulitzer Prize-winning novel Advise and Consent (1959) in which a senator is driven to suicide amid the viciousness of a cabinet confirmation hearing and then remind yourself that politics has always been a brutal business.

Concern that politics is going to the dogs has been a constant refrain in American life. Indeed it goes right back to the Founders themselves. After being the fiercest of rivals and not speaking for years, former presidents Thomas Jefferson and John Adams eventually reconciled at the end of their lives and conducted a lengthy correspondence, much of which was taken up with complaining about how badly politics had turned out since they’d retired. Each worried about popular democracy and ordinary people wielding too much power. Partisan, sectarian, and sectional conflict seemed out of control. American life, Jefferson complained wearily, had entered “a state of degradation, which I thank heaven I am not to live to witness.” All of which forgot, of course, that it had been Adams and Jefferson who had done so much to create that partisan and sectional politics in the first place, fighting one of the most bitterly contested elections of all time in 1800, when both men predicted the literal end of the Republic if the other won.

Yet somehow the Republic carried on, as it always does. Checks and balances mean only rarely does any one side get the complete upper hand—essential in a country as large and diverse as the United States. That should give some measure of comfort in the days to come. Whatever your political views, the quality of endurance represented by national election day is something to celebrate in this controversial election cycle as much it ever was. That is not Pollyannaism or exceptionalism; it is a simple statement of historical fact.

Richard Aldous, a professor of history at Bard College, is the author and editor of 11 books including Schlesinger: The Imperial Historian and host of the weekly “Bookstack” podcast for American Purpose.