Trump vs the Kennedy Center

What appreciation of the arts tells us about national identity.

When people today ponder the assassination of John F. Kennedy 62 years ago, possibly the question most asked is: Would Kennedy have pulled American troops out of Vietnam? But in light of President Donald Trump’s makeover of D.C.’s Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts, it becomes equally pertinent to inquire: What might have been the consequences of Kennedy’s espousal of a “more civilized” America?

Twenty-seven days before he died, President Kennedy delivered an arts address at Amherst College. He said in part: “I see little of more importance to the future of our country and our civilization than full recognition of the place of the artist.” Four weeks later Kennedy was poised to announce the appointment of Richard Goodwin, an inner-circle New Frontier activist, as his arts advisor. Though the president was no aesthete, he was a cultural Cold Warrior intent on challenging Soviet Russia in every department of human activity—including the performing arts in which Russia excelled. And he respected and admired his First Lady’s impassioned engagement with music and dance.

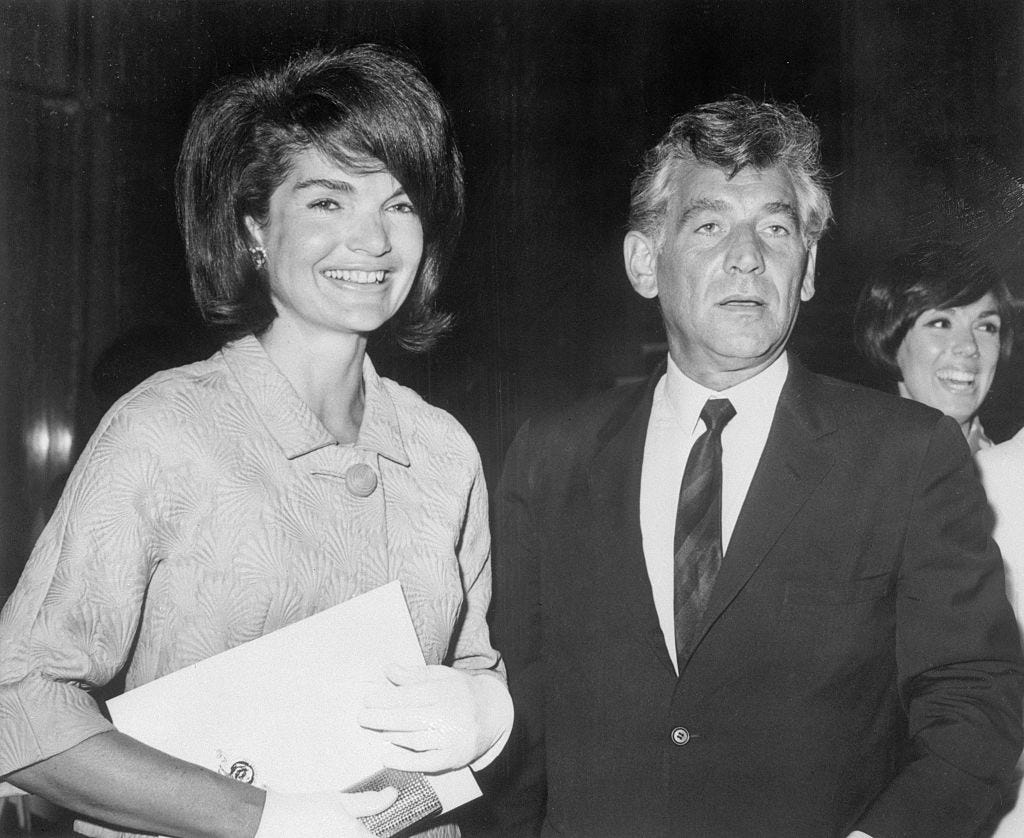

A notable third party in this endeavor was Leonard Bernstein, then music director of the New York Philharmonic. Bernstein tirelessly advocated for a more sophisticated America. When Pablo Casals and Igor Stravinsky were fêted at the Kennedy White House, Bernstein was there. He also socialized with Jack and Jackie. He saw Kennedy’s New Frontier as a beacon light for an American artistic future that could stand up to Old World traditions.

Here’s a Bernstein anecdote: In 1959, when the State Department sent him to Soviet Russia with his New York musicians, Bernstein was counselled by a Russian bureaucrat not to perform Charles Ives’ The Unanswered Question. According to an eyewitness, Bernstein arose, said “Fuck you!”, and left the room. He proudly performed (and encored) the Ives piece, introducing Russian audiences to an American musical genius. Fourteen years later, at the second Nixon inauguration, he mounted an anti-Vietnam concert at the same moment the president hosted the Philadelphia Orchestra in a program including Tchaikovsky’s 1812 Overture (with cannon blasts). Bernstein chose Haydn’s pacifist Mass in Time of War, performed to an overflow audience at the National Cathedral. He was a man who seized center stage fearlessly and effortlessly.

Neither Kennedy nor Bernstein could have envisioned the arts initiative transpiring in D.C. right now: the apparent redirection of the National Endowment for the Arts (NEA) and the National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH), the presidential plan for an NEH-funded Garden of Heroes, and the performance of the Star-Spangled Banner at all 2025-26 National Symphony concerts. Meanwhile, the president has purged the Kennedy Center board and made himself chairman. And he’s replaced the Center’s president with Richard Grenell, once a controversial ambassador, and now engaged in re-targeting arts programing “for the masses.” Among other things, Grenell has reportedly mandated a “break-even policy” for every performance. In arts administration, this is a formula bound to kill inspiration.

Most recently, Trump’s “Vision for a Golden Age in Arts and Culture” included the flagship Kennedy Center Honors: lifetime achievements awards begun in 1978. This time, they were hosted (as never before) by the president himself. The honorees, chosen with Trump’s “98%” involvement, were actor Sylvester Stallone, disco singer Gloria Gaynor, country musician George Strait, Phantom of the Opera star Michael Crawford, and the rock band Kiss—“among the greatest artists … ever to walk the face of the earth,” Trump said. Whatever one makes of that claim, previous honorees, starting in 1978 and 1979—George Balanchine, Marian Anderson, Fred Astaire, Richard Rodgers, Aaron Copland, Ella Fitzgerald, Martha Graham, and Tennessee Williams—have contributed more to an American lineage of creativity, today imperiled as never before by the erosion of cultural memory. And all this at a time when the major national charitable foundations have pulled arts funding in favor of social justice programs, and when affluent Americans are no longer as predisposed as their parents were to underwrite orchestras and museums.

So it is pertinent to ask: What might Goodwin have accomplished? And how might Bernstein have responded, were he alive today? Certainly the New Frontier would have elevated the arts as an American priority. Kennedy himself, ever the Cold Warrior, opposed direct government arts grants in favor of “free artists” thriving in “free societies”—a naïve view. But the arts endowment was already in sight. And the First Lady was an avid Russophile. Her initial guest at the White House was Balanchine, a supreme product of St. Petersburg and Paris. She sought advice on how she could help. Balanchine urged that she become America’s “spiritual savior.”

As for Bernstein—when Jackie Kennedy invited him to take over artistic direction of the Kennedy Center, he refused, but agreed to compose something for the Center’s opening concert in 1971. This turned out to be an anti-war Mass protesting the Vietnam War. It is virtually impossible to imagine him, during the decades of Vietnam and Watergate, agreeing to lead an imposed performance of the national anthem. He would have protested—prominently, loudly—the dismantling of the endowments. When in 1977 he was invited to testify in favor of a White House Conference on the Arts, he instead urged the House Subcommittee on Select Education to prioritize musical literacy: “I am sad to say, we are still an uncultured nation and no amount of granting or funding is ever going to change that” unless “reading and understanding of music be taught to our children from the very beginning of their school life.” (It also bears remembering that in Israel—a country long dear to him—Bernstein aligned himself with Teddy Kollek and other advocates of Israeli/Arab co-existence, and worried about Jewish sectarianism.)

Memorializing her husband with—significantly—an arts initiative, Jackie Kennedy envisioned a D.C. performing arts complex of international stature. Though Trump’s complaints about woke excess are by no means unfounded, the Kennedy Center has never seemed more provincial than today.

Since this nation’s founding, some have pondered whether democracy and the arts—and also whether capitalism and the arts—are somehow inimical. Certainly there is an impressive lineage of writings analyzing an American aversion to artists and intellectuals. Alexis de Tocqueville, nearly two centuries ago, observed among the citizens of the United States “a distaste for all that is old.” Assessing an expanded “circle of readers,” he discerned “a taste for the useful over the love of the beautiful,” for the “mass produced and mediocre.” Many decades later, American politicians of note included no John Adams or Thomas Jefferson—cosmopolites of humbling intellectual attainment. In 1962, the historian Richard Hofstadter produced a Pulitzer Prize-winning study of Anti-Intellectualism in American Life. He adduced a New World stereotype that holds the “genius” to be lazy, undisciplined, neurotic, imprudent, and awkward. He blamed democratization, utilitarianism, and evangelical Protestantism. An enduring philosophical argument against the American arts was launched in the 1930s by Theodor Adorno and the Frankfurt School: capitalism embraced a mistaken notion of the artist as a distant actor, unfettered and autonomous. The very DNA of American democracy—its notion of “freedom”—was in the Frankfurt view a misguided myth.

The misgivings inherent to these critiques foresaw that the American arts would suffer neglect. Neither Tocqueville nor Hofstadter nor Adorno, however, envisioned a vigorous White House initiative that would deploy the arts as an ideological cudgel. Concomitantly, a pugnacious pseudo-history stressing white Christian roots does no more favors for the arts than its woke equivalent; both pollute a necessary seedbed for creative expression. The American past is short, fragile, controversial—and precious. Today’s arts debacle is the least noticed, least discussed, least understood American crisis.

That the arts are a necessary source of national identity became the nub of Leonard Bernstein’s American vocation—until he lost faith and decamped to Vienna. It was equally understood by John Fitzgerald Kennedy. Never have Kennedy’s words sounded timelier:

I look forward to a great future for America, a future in which our country will match its military strength with our moral restraint, its wealth with our wisdom, its power with our purpose. I look forward to an America which will not be afraid of grace and beauty, which will protect the beauty of our natural environment … And I look forward to an America which commands respect throughout the world not only for its strength but for its civilization as well.

Joseph Horowitz’s books include The Propaganda of Freedom: JFK, Shostakovich, Stravinsky, and the Cultural Cold War. His book-in-progress studies Leonard Bernstein and cultural leadership. A concert producer and arts administrator of long experience, he has produced musical events at the Kennedy Center.

Follow Persuasion on X, Instagram, LinkedIn, and YouTube to keep up with our latest articles, podcasts, and events, as well as updates from excellent writers across our network.

And, to receive pieces like this in your inbox and support our work, subscribe below:

I viscerally agree with your essay, but I think you (along with most liberal thinkers) ignore an important dimension of Trump vs Liberal America: Social class. To me, the Kennedy Center and indeed the very phrase "the arts" ooze upper-class values, including a veiled contempt for the plebians who would rather listen to Nashville on AM radio than to the classical FM station, hosted by someone with a vaguely elite international accent.