The Joy of Forgotten Books

An antidote to the sorry state of American publishing.

For five months in 2023 my wife and I traveled through 28 states across the United States, in a hopeful, slightly crazy, deeply personal, and sometimes grueling search for Little Free Libraries. I had a book to deliver, a copy of my latest novel, What the Dead Can Say—and the journey revealed an astonishing range of cultural landscapes that we hadn’t expected to discover.

During those months when we racked up over 10,000 miles, Alma and I every evening consulted the Little Free Library organization’s app—which provides the location, photo, and description of nearly 200,000 participating libraries—and we’d decide which ones to visit the next day. We preferred those that featured banned books or books written by a diverse range of authors, works of literary fiction or memoir, and especially any surprising mix of books of all genres, for all ages. And while most libraries are built from the standard kit of a two-shelved, glass-doored box atop a wooden stand, we favored those whose stewards channeled their inner Outsider Artist and created little libraries of sometimes surprising beauty and individuality. In Maine, we came upon one built in the shape of a lighthouse; in Chicago, a medieval castle; in Missouri, a tiny barn accompanied by a tableau of plastic farm animals. License plate roof tiles topped another in Denver while one in Crawfordsville, Indiana was graced with the blossoming yellow stars and blue swirls of Van Gogh’s Starry Night. More than a few resembled a Tardis, Dr. Who’s iconic blue police-booth that—like a book—is larger on the inside than the outside.

Likewise, our five-month journey around the country contained within it a far longer timeframe. My wife Alma Gottlieb is an anthropologist, and for years we had lived in small villages in West Africa, among the Beng people of Côte d’Ivoire. In 1993, during our third extended stay, news of my father’s death back in the U.S. arrived in the village, too late for us to return for his funeral. Stunned, I couldn’t decide what to do, how to mourn, until village elders offered to give my American father the ceremonies of a traditional Beng funeral. After days of elaborate ritual, the village’s religious leader, Kokora Kouassi, confided to us that my father now visited him in his dreams—from Wurugbé, the Beng afterlife—with messages of farewell and comfort. The Beng believe the dead exist in an invisible social world beside the living, and Kouassi’s dreams were meant to assure me that my father wasn’t far away at all. Instead, he hovered invisibly beside me.

Soon after, I began to receive, unbidden, the first sketches of ten fictional characters. I understood immediately that they were all ghosts—American ghosts, but existing in an afterlife similar to Wurugbé. And they were all surprises. Among them was a car repairman who discovers in his afterlife the pleasures of Books on Tape; a 1950s entomologist hiding her sexual identity who, as a ghost, continues her research in an ants’ nest; a Civil War-era teenager beset by an ambiguous religious vision; the ghost of a Depression-era reporter who leaves far behind the restrictions of her former newspaper’s women’s craft page; and above all, Jenny, the ghost of a three-year-old child who, through her longing, encounters and absorbs the memories of these diverse ghosts—ghosts whose lives and afterlives encompass overlapping eras of nearly 200 years of American history. Jenny’s embrace of these inadvertent mentors opens within her windows of empathy into the difficult, essential gift of otherness.

For the next 30 years, I wrote and rewrote this novel, while publishing four other books of fiction and nonfiction. Learning the territories of this afterlife that had risen from somewhere deep within me, as well as Jenny’s challenge of balancing a growing crowd of selves within her, became the one steady creative project of my life. Yet by the time I completed What the Dead Can Say, traditional publishing had become increasingly bottom-line corporatized, the marketplace of newspaper and magazine book reviews had collapsed, and an arms-race for readers’ attention had cooked up a new marketing genre: ghost-written blurbs.

Perhaps nothing better exposed the sorry state of American publishing than the book cover style now known as The Blob: those vaguely abstract swaths of color serving as background image to the downward crawl of a book’s title printed in blocky letters, followed by the author’s name below in smaller font. When laid out on a bookstore’s New Arrivals table, they all appear incestuously related. Publishers had decided that this design “pops” as an Internet thumbnail image. And so they must be repeated ad nauseam, no matter how disrespectful to writers saddled with a cookie-cutter cover enlisting them as team players for a corporate sales scheme. Meanwhile, the designers churning out this template are reduced to the role of a fast-food restaurant manager: seemingly in-charge, but taking strict orders from above.

It’s all about agency—or the lack thereof.

Though I’d published work in The New Yorker, Paris Review, and Washington Post Magazine, and books with Scribner, Random House, and the University of Chicago Press, I hesitated entering once again into a system that, more than ever, threatened to strip away whatever agency I’d nurtured during the long years of writing a novel whose initial inspiration had been so deeply personal. What the Dead Can Say had already been vetted by the careful readings of fellow writers and editors via the publication of numerous chapters in literary magazines, so why seek further approval from a publishing world I’d come to distrust? If I truly believed in my book, why not embrace the entrepreneurial spirit of an independent filmmaker—and maybe, in the process, break more than a few rules?

I sought out like-minded designers, and we came up with the format for a book with a stark design that rejected the usual reflexive sales pitches. No praise-song of blurbs on the back cover. No plot summary spoilers on the inner flap, or braggy author bio on the back flap. No title or author’s name on the front cover, only a haunting black-and-white photo that seemed to hover in midnight air. On the title page, only the pseudonym “Author Unseen” appears. There’s no bar code to be found because, just as my novel’s appearance was meant to be a critique of book production clichés, so would the distribution of its 1,000-copy press run. What the Dead Can Say would be a mysterious gift delivered to readers through the under-the-radar network of Little Free Libraries spread across the country—readers unlikely to discover my novel had it been published in a conventional manner. And even though I’d know where each copy landed, I’d also be giving it the freedom of an unknown fate. Its imagined world would belong to someone else.

Little Free Libraries, I’d come to appreciate, specialize in surprise—including the often unpredictable contents of their shelves. In bookstores, surprises are necessarily squeezed from the system. For commercial reasons, books are kept together by subject: poetry in its own section, and the same for fiction, nonfiction, cookbooks, and travel guides. Otherwise, how can customers easily find what they’re looking for? In public libraries, categories matter even more: if you need a book about volcanoes, you can locate ten of them side-by-side on a nonfiction shelf but nowhere else. A little library, however, can be a glorious mishmash. A children’s book might lean against a novel about zombies, followed by an anthology of Japanese poetry and a well-worn paperback copy of James Baldwin’s The Fire Next Time. It’s enough to give the Dewey Decimal System a headache.

And it’s mishmash all the way through in this country that Alma and I had been driving across for months. What a wide range of neighborhoods we encountered in every town and city, from mini-mansions to inner city streets. When we’d lived in the Midwest, how many times had we driven past Columbus, Ohio? But during our trek we spent an entire day in that city, searching for Little Free Libraries in ordinary neighborhoods, and on streets that few people drove on unless they already lived there—streets that no tourist would think to visit. Yes, they were ordinary, but also able to surprise. One little library, besides its selection of books, offered packets of ramen noodles, cans of vegetable soup, and dog treats; another had glued down on its roof a carefully arranged scene of Playskool figures enjoying a day at the park; and in the city’s German Village district, a little library had been fashioned from the frame of a beekeeper’s apiary. Each display of individuality offered a hint of a street’s shared personality.

We encountered this playful, hopeful, and generous spirit everywhere—a budding literary tradition far from the commercial imperatives of the publishing industry. Little Free Libraries ignore the digital grid. Reading habits can’t be tracked by an algorithm, and there’s no purchase to be monitored by a credit card or website. This mishmash of the by-now 200,000 little libraries is like the root system of a tree, a network that does essential work underground.

Our political and cultural landscape is a mishmash too. The Electoral College votes assigned to states may be monolithic, but the lives of the people who live there are far more varied and nuanced. In “red” as well as “blue” states we saw Pride flags, No Hate Here, and BLM signs on front lawns. Everywhere we saw interracial couples and families. We came upon two vibrant arts districts in Oklahoma City; an LGBTQ-friendly coffee shop in downtown Wichita, Kansas; an African grocery on the outskirts of Columbia, Missouri; a large field of solar arrays bordering corn fields in Wisconsin; and in the High Plains states of Kansas, Oklahoma, and Texas, thousands of giant wind turbines. In Denver, a neighborhood of mansions stood a mere handful of blocks from an abandoned homeless encampment. A single tree-lined street in Columbus, Ohio, displayed an insurrectionist flag, Pride banners, Black Lives Matter posters, and a Trump sign. The “two Americas” breathe the same air.

We encountered perhaps the starkest example of this proximity in Topeka, Kansas. On one side of a street, a house painted in rainbow-stripe Pride colors (along with its vandalized little library) waged a silent, seething spiritual war against the notorious Westboro Church on the opposite side of the street, whose signboards proclaimed “God hates fags.” Our deep divisions, having become an increasingly integral part of our country’s mishmash, now threaten to pull us apart.

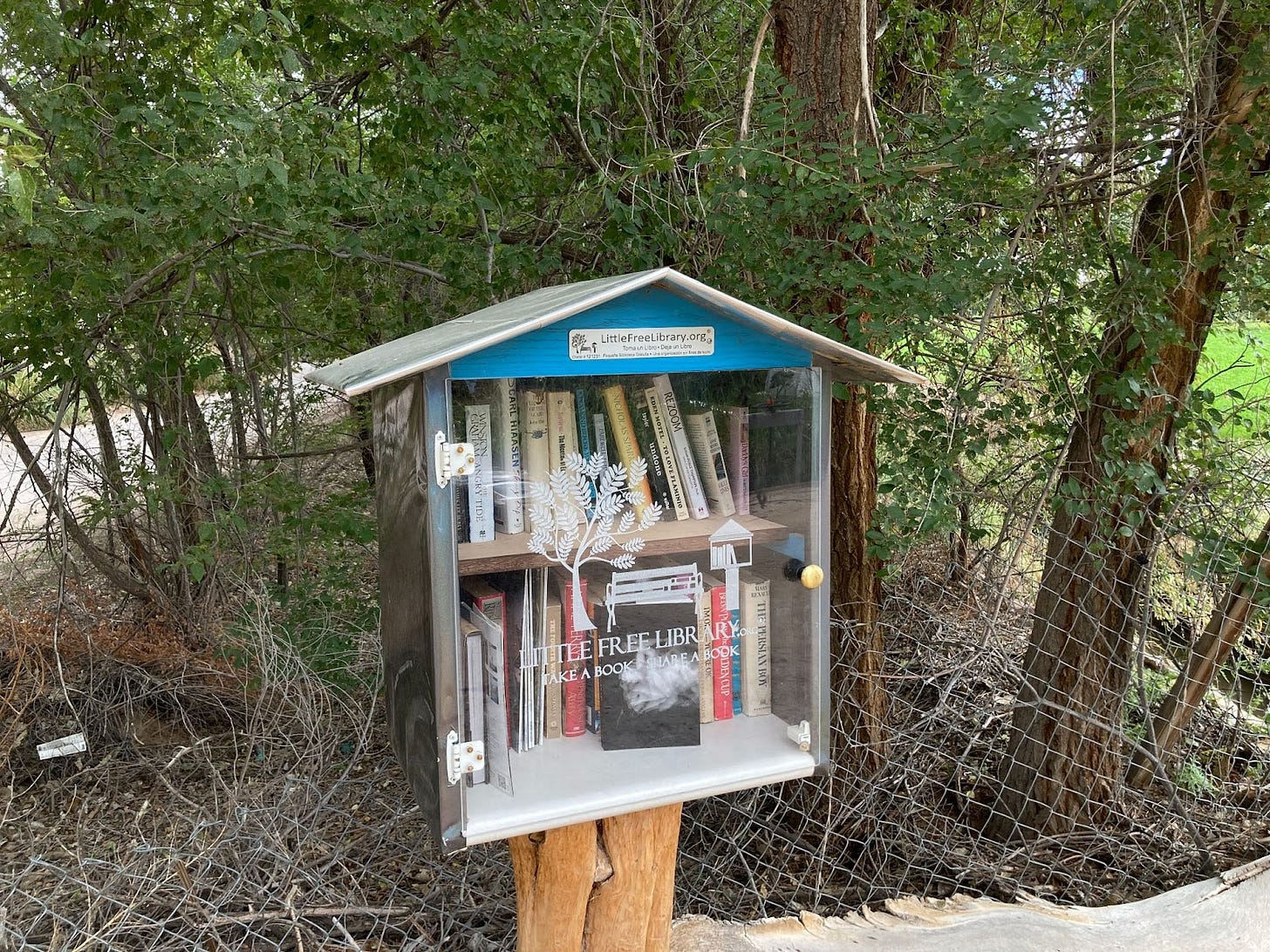

But a Little Free Library that Alma and I discovered on a dirt road outside of Albuquerque, New Mexico offered a more promising take on the state of our cultural glue. This library stood near a traditional irrigation canal—an acequia—that channeled water from the nearby Rio Grande to the surrounding farmland. The usual welcoming motto, “Take a Book. Leave a Book,” was echoed by a Spanish version: “Toma un libro. Deja un libro.”

This bilingual greeting reminded me that the Spanish word acequia itself comes from a third language, the Arabic as-saqiya. The word means “water conduit,” but it can also mean “to drink water,” or “to give water.” In other words: You receive, you give. In other words: You take a book, you leave a book. In other words: Toma un libro, deja un libro.

The library’s shelves hosted an unusually rich mix of books, beginning with two novels ripe for any censor’s list: The Satanic Verses, Salman Rushdie’s magic-realist masterpiece that has haunted him nearly to death; and The Persian Boy, Mary Renault’s historical novel about the eunuch who was once Alexander the Great’s lover. Then there was Skinny Dip, Carl Hiaasen’s detective caper, and a thriller by James Lee Burke; P. D. Ouspensky’s The Fourth Way, which—channeling the Greek-Armenian philosopher Gurdjieff—advocates a “waking sleep” of higher consciousness; One-Handed Pianist, Ilan Stavans’ story and essay collection about growing up Jewish in Mexico; The Changing of the Guard, an atypical Hollywood novel by John Ehle, a writer often described as “the father of Appalachian literature”; some lighter reading by Nicholas Sparks and Belva Plain; the self-help book, I’m OK—You’re OK; and even a college algebra textbook.

This welcome mishmash of books—like the collections of many little libraries we encountered—reassured me that the communal endeavor of our diversity just might be irrevocably embedded in our country, just as my fictional character Jenny’s array of diverse ghosts are embedded in and enhance her afterlife, just as Little Free Libraries are larger on the inside than on the outside. We are all, in fact, diverse within ourselves. How could it be otherwise? We are shaped by the many voices of the different people we’ve met; by the people we ourselves have been during various stages of our lives; and by the community of authors and fictional characters in the books we’ve read that accompany us on journeys of self-revelation. We are, and will remain, diverse through the words we read, the art we make, the languages we speak, and, like it or not, even the air we share to breathe.

Philip Graham is professor emeritus of the University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign, and co-founder and Editor-at-Large for the literary/arts journal Ninth Letter. His most recent book, the novel What the Dead Can Say, was initially delivered anonymously to Little Free Libraries across the country.

Follow Persuasion on X, LinkedIn, and YouTube to keep up with our latest articles, podcasts, and events, as well as updates from excellent writers across our network.

And, to receive pieces like this in your inbox and support our work, subscribe below:

Thanks so much for this lovely post, Philip! I am a collection development librarian in Colorado (buyer of non-fiction) and agree wholeheartedly with you about the publishing industry. I'm so tired of having to buy half-baked celebrity memoirs (as just one example) because that's where they put their advance and marketing money. I do want to put it out there that we public librarians are doing our best to bring hidden gems to our patrons. I also appreciate your nuanced commentary on the political situation in the US, especially the notes of hope you sound. I wish your book the best of luck and wish we could have it in our collection. I'll see about getting the digital version for myself even though I am usually a hard-copy old-school print girl. :)

Samuel Johnson, who will be remembered long after we are forgotten, was quoted as saying "No man but a blockhead ever wrote, except for money." Is that a bit of archaic 18th century wisdom or is it true today?