The Kingfish Lives

On its 75th anniversary, "All the King’s Men" reminds us of the enduring appeal of the politics of resentment.

Robert Penn Warren’s All the Kings Men, published seventy-five years ago in 1946, was a critical and commercial success and won the Pulitzer Prize for fiction. Primarily a poet over his long and acclaimed career, Warren said that he never intended the novel to be about politics, even though it is widely regarded as one of the best of the political genre.

Warren’s vision is wide and deep enough to transcend affairs of state and dive into the riptides of the human condition. The story of Willie Stark’s rise and fall, from a naive country lawyer to a powerful and ruthless demagogue, is only a springboard for Warren’s deeper meditations on the roots of demagoguery, the weight of history and idealism, and what it means to understand the difference.

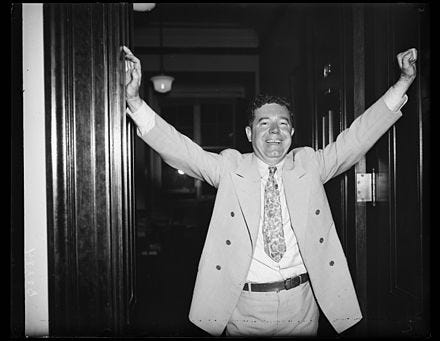

Willie Stark is a fictionalized version of Governor Huey “the Kingfish” Long. Long is still a legend in his home state of Louisiana, which is more lightly fictionalized as the novel’s main setting. Long’s politics were a now-rare but once fairly common mix of strident progressivism and down-home irascibility—imagine Bernie Sanders melded with Machiavelli and LBJ. Long never made any bones about his country roots; if anything, he flaunted them whenever he could. He combined folksy charisma with a steely eyed determination to get things done, almost entirely his way.

One quote of Long’s on governance is archetypal: “Those of you who come in with me now will receive a big piece of the pie. Those of you who delay, and commit yourselves later, will receive a smaller piece of pie. Those of you who don’t come in at all will receive—Good Government!”

Willie Stark is similarly cavalier about how politics really works. His casual corruption, which might have shocked readers in 1946, is now widely taken for granted. When I moved to New Orleans after many years in Boston, which has its own tradition of rascal kings, I wasn’t surprised that many locals, years later, still spoke fondly of Long.

Warren’s Willie Stark, after informally studying law, gives an early political speech in which he rattles off facts and figures about state policies and tax rates. Some have cited the speech as evidence of Willie’s idealism, but that isn’t quite right. Willie does assume, reasonably enough, that voters will want to get accurate information about the issues they’ll be voting on. He doesn’t yet understand the extra razzle-dazzle a politician needs to really move the crowd and thereby climb the power ladder.

Willie’s informal adviser—Jack Burden, a cynical former newspaperman—sets Willie straight: “Just stir ’em up, it doesn’t matter how or why, and they’ll love you and come back for more.… It’s up to you to give ’em something to stir ’em up and make ’em feel alive again. Just for half an hour. That’s what they come for. Tell ’em anything. But for Sweet Jesus’ sake don’t try to improve their minds.”

The politics of stirring ’em up, aided by a media apparatus unknown in Willie’s time, is alive and well on today’s internet. People in both the media and the inner circle of former President Donald Trump have noted that the former reality TV star’s knowing how to thrill the crowd got him farther than most people ever thought he could go.

Willie hears Jack’s wisdom the night before he has to give his big speech. He’s pacing and drinking copious amounts of “likker,” a perfect metaphor for what gets the wheels of political speech turning. Some politicians brew that elixir naturally, tapping into internal reservoirs of intoxicating charisma. Other perfectly decent and capable politicians never learn the recipe. But you have to have that likker pouring out of you to get the audience’s juices flowing.

This Willie does, telling of his own humble background to prove his authenticity. Fighting a raging hangover, he tosses away his prepared speech and thunders, “This is the truth: You are a hick, and nobody ever helped a hick but the hick himself. Up there in town they won’t help you. It is up to you and God, and God helps those who help themselves!”

The crowd starts sullen but is gradually won over, sensing that Willie is one of them and responding to his strike at their sore spot of unconscious grievance. It’s the way politicians, particularly on the right, stoke a sense of social victimhood and subsequent cultural condescension in their voters, portraying themselves as the people’s true champion. Willie ends by leading the crowd in a shout of “Nail ’em up!”—more ominous than routine speechifying, portending something very dangerous, and especially relevant today.

Willie’s performances ultimately put him in the seat of power. Once there, he doesn’t really have an ideology: You don’t need much intellectual or moral effort to shake your fist at those bums in Washington. But mere discontent isn’t a critique; it doesn’t offer any productive solutions to real problems. Now, as then, it’s easy to define your politics by what you’re against rather than what you’re for. Warren lets us see that Willie is a demagogue, even though he retains some egalitarian impulses. For example, he becomes obsessed with building a free public hospital, an undoubtedly good thing. But Willie’s social vision is drastically limited, much more so than Huey Long’s. For Willie, a hospital isn’t just, or even mainly, a way to help poor people; it’s an opportunity for him to build his brand, extend his reach, and give more people reason to support him.

What Willie doesn’t realize is that this type of public investment will end up hastening his downfall. Willie cajoles Jack into recruiting Adam Stanton—Jack’s childhood friend and the brother of Jack’s lost sweetheart, Anne—to run the hospital. Adam is an idealist; Willie doesn’t understand how deep and intractable Adam’s idealism really is.

Stoic, reticent Adam has “clear, deep-set, ice-water-blue, abstract eyes—the kind of eyes and the kind of look your conscience has about three o’clock in the morning.” Adam has a kind of rigid moral purity that will break but cannot bend. His rectitude is alien to the casual realpolitik of Willie and Willie’s gang. Adam balks at taking Willie’s opportunity at face value. In fact, he finally exacts retribution against Willie, who ends by suffering the same fate that Huey Long did, albeit for different reasons.

As days and pages pass, All the King’s Men gradually takes on the hazy atmosphere of noir. Willie increasingly acts like a mob boss, doling out rewards and punishments in smoke-filled back rooms, flanked by enforcers and loyal henchmen. Jack does plenty of private investigating at Willie’s behest, strictly off the record, that wouldn’t be out of place in a Raymond Chandler novel. At times, All the King’s Men is steeped in a sense of universal, inexplicable, almost cosmic guilt, a key noir trope. As Willie directs a hesitant Jack to dig up dirt on an enemy, he opines, “There is always something.… Man is conceived in sin and born in corruption and he passeth from the stink of the didie to the stench of the shroud. There is always something.”

And there is indeed always something. Jack, despite his reluctance, ends up uncovering long-forgotten scandals that lead him into seedy locales where lost souls sit brooding over sins of the past. The fact that these buried secrets are ultimately used by a ruthless politician doesn’t change the fact that they are real. The tellingly named Jack Burden, though he sarcastically claims to be an amateur historian who loves truth, goes about his spadework with a world-weariness that comes with a realistic view of how the world works but with just enough lingering idealism to make him tragic. He murmurs, “If the human race didn’t remember anything it would be perfectly happy;” and we come to know the heaviness of what he learns about the world that he is a part of whether he likes it or not.

Jack ends up digging deep into the foundation of his grandly declining ancestral home and discovers how much bought and sold human blood lies at its root. Jack’s finally coming face-to-face with America’s original sin darkens his understanding of his family and his country’s history. He ends up theorizing somewhat blithely about the Great Twitch, where cause and effect aren’t as clear-cut as scientists or philosophers might think; he comes to the fatalistic conclusion that “all life is but the dark heave of blood and the twitch of the nerve.”

This formulation is a beautifully put cop-out: It’s relatively easy for Jack’s wounded moral sense to focus on the limits of human culpability and to retreat repeatedly into what he calls the Great Sleep, snoozing and brooding alone in dingy hotel rooms with occasional restless trips out West. If you feel responsible for what’s gone before but have given up the will to change things because of complicity or cowardice, the assumption that things “just happen” becomes very appealing. Jack is rueful over how his once-promising life turned out, and yet remains sentimental about the innocence lost through the remorselessness of Willie’s appetites and egomania. Jack’s thwarted romance with Anne Stanton, his high school sweetheart and in some ways his muse, is one of the most devastatingly realistic stories of disappointed teenage love ever written. When I re-read it years later, I found that it wounded me all over again.

Contrary to the usual interpretation, Willie isn’t the novel’s most important character. Plenty of opportunistic types came before him; Willie’s ambitions are nothing new. But Jack’s moral anguish and its connection to his working for Willie are central to the novel’s interior drama. Most of the story takes place within Jack’s psyche, which is probably why the various movie adaptations fall short of the novel’s haunting power. The novel’s most compelling moments aren’t Willie’s speeches; they occur when Jack grapples with the implications of his discoveries, which discredit upstanding members of his community and cast aspersion on his sentimental view of his people and his own past. The moral implications of this kind of knowledge clash with his allegiance to the boss:

The end of man is knowledge but there’s one thing he can’t know. He can’t know whether knowledge will save him or kill him. He will be killed, all right, but he can’t know whether he is killed because of the knowledge which he has got or because of the knowledge which he hasn’t got which if he had it would save him.

The price of that knowledge is the realization that all that glitters is not gold, whether in life or in politics. At one point Jack cites what the Roman emperor Vespasian said about his tax on the use of public urinals: Pecunia non olet (money doesn’t smell). That mordant motto could be posted above any of the smoke-filled back rooms where the deals really go down, whether or not they result in something good for the people. When Jack ponders the implications of Willie’s insistence that “you have to make the good out of the bad, because otherwise you don’t have anything else to make it out of,” he can’t help but concede the point, even if it pains what’s left of his ragged conscience. Jack doesn’t necessarily trust Willie’s ambitions and is disgusted by his more primal desires, especially when they involve Anne. Yet his expectations are colored by a life spent digging up the kind of history they don’t tell you about in school.

All the King’s Men doesn’t flinch at laying out its painful truths about looking hard and long at what you would rather look away from. It teaches useful if uncomfortable lessons about how Americans think about power. Plenty of people still like to suspend disbelief about the candidates that intoxicate us and to romanticize a past that isn’t as rosy as we pretend it is. Faulkner’s immortal observation, “The past isn’t dead, it isn’t even past” lays the foundation for what troubles Jack, and the novel even expands on Faulkner by showing what those unquiet memories do to the present. Seventy-five years on, Warren’s poetic and unflinching tale still has much to say to anyone who tries to stay historically conscious as a citizen of a country that is often willfully ignorant of the forces that inexorably shape our present.

Matt Hanson is a contributing editor of American Purpose and The Arts Fuse, Boston’s online independent arts and culture magazine. His work has appeared in The Baffler, The Guardian, The Millions, The New Yorker, The Smart Set, and Three Quarks Daily.

Photo by Harris & Ewing, LOC: Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=47823585