The Mahlers in Manhattan

Joseph Horowitz's new novel weaves a vibrant tapestry of Gustav and Alma Mahler's life in fin-de-siècle New York.

The Marriage: The Mahlers in New York

by Joseph Horowitz (Blackwater Press, 255 pp., $18.99)

Several years ago, I began an essay on Gustav Mahler by describing him as the quintessential “composer of contradiction and complexity.” He is not simply a composer who will somehow convince you that the sky is black, only to then turn around and convince you it’s blue after all. He is the composer who actually seems to believe, with all his heart and intellect, that the sky is both black and blue at the same time. His music is not merely happy then sad, it is both and neither simultaneously. Acquaintance with Mahler’s biographical details will quickly reveal that the man was just as complex and contradictory as his music.

Classical music historian and author Joseph Horowitz, in “endeavoring to draw as close to [Mahler] as I can,” has produced a worthy manifesto in his new novel, The Marriage: The Mahlers in New York. It is to Horowitz’s credit that, in the best Mahlerian spirit, drawing Mahler as close as possible is both what the novel is about, and also what it is not about. It is also a book about New York, a book about music criticism, a book about failure, and, of course, a portrait of a marriage.

Mahler’s complexity is one reason why, even over a century after the composer’s death and fifty years since his music became part of the mainstream, so many people get him wrong; they only get part of him. A biographer sees his nearly infinite vulnerability, mistakes it for neurosis, and completely misses the steely strength that enabled him to command the Vienna Opera as no one since has been able to do. A critic decries Mahler’s retouching of a Schumann symphony as violating the spirit of the work, without noticing that Mahler has managed to convey the content of the composition with a degree of lucidity that could not otherwise be achieved in an orchestra and concert hall more than twice as large as any Schumann could have imagined.

One result of this complexity is that most people interested in Mahler tend to feel the need to counterbalance the excesses of their predecessors or rivals. If ever there were a subject area about which commentators would be well advised to regularly ask themselves, “Am I just being contrarian?”, it is the life and music of Gustav Mahler.

Horowitz is self-aware enough to recognize his instinct to counterbalance the image of Mahler in New York created by Mahler’s most important biographer, Henry-Louis de La Grange, pointing out in his afterwards that de La Grange’s “admiration for Mahler the musician, and love of Mahler the man, ultimately did not permit him a fair view of New York generally, and of [longtime New York Tribune music critic] Henry Krehbiel particularly.” While noting that “De La Grange’s Mahler biography will remain a basic and invaluable resource,” Horowitz suggests that de La Grange’s “adulatory tendencies will remain . . . a straw man against which to measure Mahler’s merits and demerits. Mahler was a great personality whose . . . shortcomings and vulnerabilities were merely human.”

In a novel of so much value, the central triumph is not Horowitz’s ability to humanize Mahler, but to have provided readers—for the first time in my experience—with a nuanced, believable, balanced, and compelling portrait of Alma Mahler. Like her husband, Alma’s was a complex and contradictory personality, and this has made it easy for writers to appropriate her for their own ends.

To some, Alma remains the villain in Mahler’s life story—the woman who broke his heart and his health, and whose writings were so full of misleading and dishonest details about the man that she damaged his posthumous reputation far more than any critic. Her antisemitism and alcoholism have not made her a particularly sympathetic figure, either. To others, she was the innocent victim of Mahler’s misogyny, a woman denied the opportunity to exist on her own terms and forced instead to be “wife and mother” to the great man, to serve the cause of his genius. Neither of these extremes is credible.

Horowitz’s Alma is the first incarnation of her this author has encountered that actually seems like a real person. And, fittingly for a book entitled The Marriage, the novel is as much, if not more, hers as her husband’s. There are so many questions about Alma and her marriage to Mahler, and most of them begin with “Why?” This was the first book in which I felt like I was getting believable answers.

I don’t think it would be unfair to suggest that Horowitz shares a few of de La Grange’s “adulatory” tendencies for two characters in the novel: Mahler’s nemesis, music critic Henry Krehbiel, and his towering musical predecessor Anton Seidl. But as Horowitz notes about de La Grange, this is not at all a bad thing, especially when writing about two tremendously compelling figures the memory of whom has largely faded from history.

Krehbiel—portrayed through a fascinating mélange of observation by other characters, his writings (both real and imagined), and his own narrative thoughts as conjured by the author—is the more immediately human of the two. One gets the feeling that Krehbiel never really recovered from the loss of Seidl, who was both his hero and friend. In his sometimes caustic criticisms of Mahler’s interpretations, one can sense that Krehbiel is often really mourning the loss of Seidl’s unique brand of music making. Seidl’s extremes of tempo and Wagnerian approach to performance were examples of genius, while Mahler’s tampering with orchestration struck Krehbiel as a toxic mixture of egomania and a lack of understanding of the originals.

The tragic irony in this is that Krehbiel’s writings (both real and imagined) reveal countless blind spots of his own. Averse as he was to what he perceived as Mahler’s penchant for gigantism in bringing extra brass to Schubert and Beethoven, he doesn’t appreciate Mahler’s careful pruning of textures that allowed important thematic ideas to come through with a clarity that is otherwise hard to achieve when playing classical and early Romantic works with large forces.

And, of course, Mahler’s own music is Krehbiel’s biggest blind spot of all. More than once, associates suggest to Mahler that Krehbiel’s hostility was due, at least in part, to Mahler’s indifference. And it is to be regretted that while Mahler is seen in many scenes in the novel to embrace compromise and to show true pragmatism and an openness to feedback, on the subject of Krehbiel he is completely unyielding, and this seems to have truly wounded Krehbiel.

Horowitz portrays Seidl not as a character in the novel, but as a memory of one—a memory of a fallen hero whose shadow looms over the tragic events Horowitz captures so poignantly. As such, he emerges as perhaps the figure one most looks forward to learning more about.

And what of Mahler? Horowitz indeed draws us as close to Mahler as can be done, but the wonderfully Mahlerian result of this is that the Gustav Mahler of The Marriage emerges as more unknowable and sphinx-like than ever. How wonderful that the composer who bared his soul in his music more nakedly than perhaps any other could seem so strangely unknowable to everyone around him in this superb piece of historical fiction, and to those of us still fascinated by him today.

Kenneth Woods is artistic director of Colorado MahlerFest and the English Symphony Orchestra.

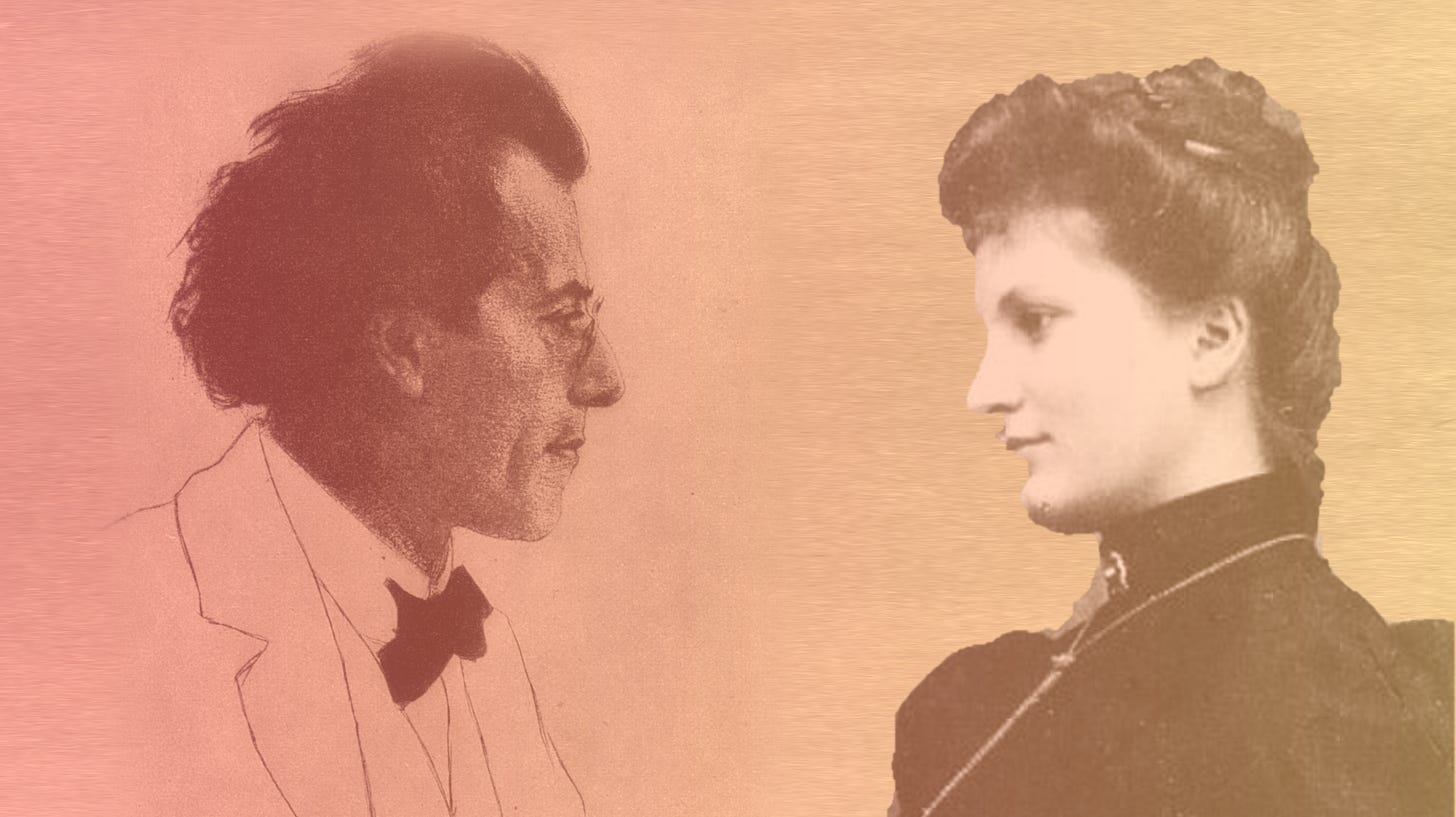

Images: Gustav Mahler (L), adapted from an etching by Emil Orlik, Groves Dictionary (Wikimedia Commons; public domain, originally published 1903). Alma Mahler-Werfel (R), (Wikimedia Commons; public domain, originally published 1899)